arnica montana

arnica montana

the desperate

tearing down the highway

like they got no place to stay

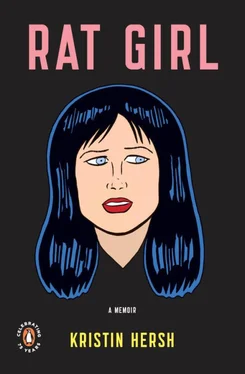

The Bullet and I are doing the thirty-minute drive from Providence to Aquidneck Island together so I can swim laps and shower at the Y before school. Like most of the people in Napoleon’s gang of losers, I’m eighteen—the age where no one takes care of you—so most of my showers are taken at the Y. I’m not homeless per se—I just can’t stop for very long. I’m too… wired. And I have this idea that you could belong everywhere rather than just one place, so I don’t call anything “home.” Don’t know what I’d do there if I did. I’d just get antsy and wanna leave again.

People who suffer because they have nowhere in particular to go are those who can sit still, who sleep. I stopped doing these things last September, when I made a mistake and moved into the wrong place: a bad apartment christened “the Doghouse” by someone who painted that on the door. The Doghouse was the last place I played music on purpose, of my own volition.

I innocently stepped through the door of the Doghouse and put my stuff down because I thought that if I lived alone for a while, music might speak to me, tell me its secrets. Music spoke, alright—it yelled—and as it turns out, it has no secrets. If you ask music a question, it answers and then just keeps talking louder and louder, never shuts up. Music yelled so loud and so much in the Doghouse, I can still hear it.

I was used to sound tapping me on the shoulder and singing into my ear. I’ve heard music that no one else hears since I got hit by a car a couple years ago and sustained a double concussion. I didn’t know what to make of this at first, but eventually I came to feel lucky, special, as if I’d tapped into an intelligence. Songs played of their own accord, making themselves up; I listened and copied them down. Last fall, though, the music I heard began to feed off the Doghouse’s evil energy. Songs no longer tapped me on the shoulder; they slugged me in the jaw. Instead of singing to me, they screamed, burrowing into my brain as electricity.

I got zapped so bad in that apartment, I don’t think I’ll ever rest again. In the Doghouse, sleep stopped coming, days stopped ending—now sleep doesn’t come and days don’t end. Sleeping pills slow my thinking, but they can’t shut down my red-hot brain. If I do manage to drop off, wild dreams wake me up. So I’m different now; my thinking is liquid and quick, I can function at all hours. My songs are different, too, and when I play them, I become them: evil, charged.

I’m actually head over heels in love with these evil songs, in spite of myself. It’s hard not to be. They’re… arresting.

Before I disappeared into the Doghouse, the songs I heard were not devils, they were floaty angels. Gentle and meandering, interesting if you took the time to pay attention, but they wouldn’t necessarily stop you in your tracks. Now the songs I bring to my band are essential, bursting: harsh black-and-white sketches that my bandmates color in with their own personal noise. These songs grab your face and shout at it.

Do you want your face grabbed and shouted at? Probably not; at the very least, it’s irritating. But now that it’s happened to me, I know that music is as close to religion as I’ll ever get. It’s a spiritually and biologically sound endeavor—it’s healthy.

Some music is healthy, anyway. I know a lot of bands who’re candy. Or beer. Fun and bad for you in a way that makes you feel good. For a minute . My band is… spinach, I guess. We’re ragged and bitter. But I swear to god, we’re good for you.

When I finally left that messed-up apartment, I swore I’d never go back. I stuffed my guitar case full of frantic songs I’d scribbled down on a hundred pieces of paper, then took a minute to squint through the noise and try to figure out what exactly made the Doghouse so dark. It looked like a plain old apartment to me: wood floors, silver radiators, paint-flecked doorknobs and smudgy windows. Why this place and not, say, the house next door? Who knows, maybe the whole block is evil.

But by the time I raced out the door and took off in the Silver Bullet, it was too late. I was branded; tattooed all over with Doghouse songs—each one a musical picture etched into my skin.

I know that when my band plays these ugly tattoos, people can see them all over me, but I don’t care too much. I mean, shy people are generally not show-offs, but the burning that the songs do, the fact that I’m compelled to play them, makes me think they… matter? Maybe that’s not the right word. That they’re vital. And I respect that. I can feel sorry for myself without judging the music.

Comfort isn’t necessarily comfortable, after all; sometimes you gotta wander into the woods. Everybody knows that.

I never did go back there. Sometimes I park the Silver Bullet across the street from the Doghouse and stare at it, wondering what the hell is up with that place, but I don’t go inside. I know if I did, the walls’d close in. I made it out with my guitar and my brain, so I can look on the bright side: I got some wild songs out of it and I have evil’s big balls working for me now. Evil seems to know what it’s doing, though it isn’t ever very pretty.

Doghouse songs are definitely not pretty—they sound like panicking—but they are beautiful. The cool thing they do is, they make memories now. A syringe of déjà vu injected into my bloodstream. All the best stories work this way, but a song has the ability to tell a nice loud story. Louder than orange.

Which has made my band a work of obsession, a wholly satisfying closed circle. My bandmates and I are both conceited and pathetic about this: we think we’re the best band in the world and that nobody’ll ever like us. We play in clubs because that’s what bands do, but we don’t expect anybody to show up.

Really, we’re just on our own planet, so it wouldn’t make sense to give a fuck about anybody else, which is sorta nice. If I had to survive the Doghouse to earn this planet, I’m okay with that; it’s a swell planet. I’ve spent a lot of time on it—almost twice as much as someone who sleeps. And this lingering Doghouse energy means that I can keep going, keep moving, keep looking around. I learn a lot, being awake all the time.

For example, I learned this: we should belong everywhere .

calm down, come down

calm down, come down

i don’t wanna calm down

i don’t wanna come down

On the lawn next to the library, I sit in the sun, my textbooks stacked beside me, and look for Betty. Peering through groups of college kids, I try to catch a glimpse of her hair. Betty’s hair changes daily, so I’m not exactly sure what I’m looking for, except that she’s about fifty years older than all the other students, so it’s usually gray, champagne or white.

Betty and I have a study date. I know I could go inside the library and start studying without her, but we go to school on the island, right on the water, and it’s just too beautiful out here. I avoid going inside buildings whenever possible, anyway; I kind of… disagree with them. Shouldn’t we live outside?

Betty says this is never going to happen ’cause nobody else wants to live outside, just me. She says I need to learn to like buildings, that buildings aren’t something you’re even allowed to disagree with. “They’re everywhere,” she says. “And sometimes, you need to go inside them. Get used to it.”

Читать дальше

arnica montana

arnica montana