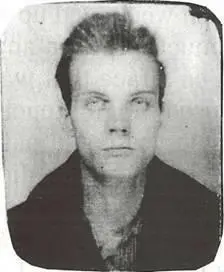

This is my old beau Rob Roy. He’s got a campy tale — he became the Baron von Lichtenstein. And he was a sheik, even though this picture looks like a rogue’s gallery shot. Lichtenstein is this tiny country, and right after World War II Rob Roy was in Lichtenstein in the black market. He met someone in Lichtenstein — a prince or a duke or something like that — and he made Rob Roy the Baron von Lichtenstein He didn’t call himself the Baron von Lichtenstein very much. It would have been a little ridiculous, this poor guy in Philadelphia starving most of the time — the “Baron von Lichtenstein.” He was a hotel clerk when I met him in 1954, and he played piano in a gay bar. Him and I were pals more than lovers. I really did love him and he did love me, but there were just too many other things going on. I wonder what happened to him.

I’ve done a lot of things since I came back to New York besides being a chanteuse. I’d take work as a stitch bitch in off-times, and in 1957 I was discovered by the celluloid medium. It wasn’t MGM, it was Avery Willard and his Avegraph Films. They were silent movies, mostly eight millimeter, with lots of queens in these campy tales. On one of my last films, Avegraph introduced Avetone, the poor man’s Vitaphone. Once in a blue moon the Avetone would get together with the picture in synch, but usually the dancer would come out and the singer would start, or I would start talking and a low man’s voice would come out. After a while, Avery started filming the leather boys, so he could no longer get me to work for him.

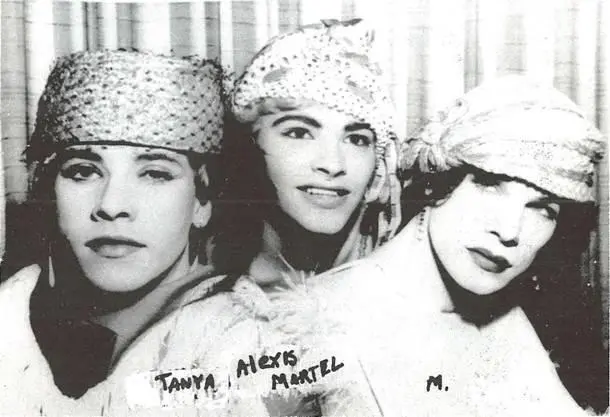

One of the best parts of my Avegraph film career was meeting my friends from the Ridiculous Theatrical Company on the set of the last film. My Ridiculous friends and I were supposed to be a Ten Cents a Dance place, and the Avegraph cinematographer brought back some Moroccan hashish. Honey, nobody wanted for nothing that night.

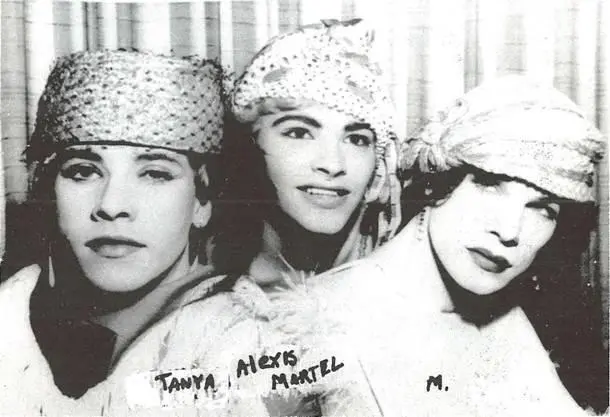

I was dancing with Lola Pashalinski — she was twice her size today — in a red zoot suit and Charles Ludlam was wearing earrings that this sailor was trying to eat off. Lola is fabulous — a diesel dyke at heart but she can play a soubrette or sing opera without lessons, and Charles is brilliant. I owe a lot to my Ridiculous friends, because they taught me how to eat right. Even though it sometimes gets dear, I always eat the right food — as organic as possible.

I’ve just finished a part in a silent movie Charles Ludlam has made with all the Ridiculous people and Crazy Arthur, “The Sorrows of Dolores.”

It was I who introduced Crazy Arthur to the Ridiculous company and they re-introduced him to show business. As a kid he’d been a burlesque comic that worked the Loew’s circuit and now he was Orgone, the hunchback pin-headed sex maniac in Turds in Hell, one of the great Ridiculous productions. I told Crazy Arthur to come today, but I think he wanted you to interview him lying down in bed. You just tell him, “Mother, it’s not nice to talk with your mouth full.”

Besides my Avegraph career, I was used for the soundtrack of the movie “The Queen.” I sang “Am I Blue.” I started with that song at three years old and there I was still singing it.

The Queen’s producer, Flawless Sabrina, came up to me at the Crazy Horse where I was working. Flawless Sabrina was actually very unflawless, sort of like a World War II record, which would crack if you looked at it. “One night, $50,” she says, so I said okay. It turned out the band was Sam the Man Taylor, who I had played with a few years before in Hazelton, Pennsylvania, so that was gay. But the Flawless Sabrina was another story. She thought she had removed all the professional impersonators from the film, but little did they know that Mario Montez was a professional. She was in the classic, “Flaming Creatures,” and all those Andy Warhol films. In this show of Flawless Sabrina’s, they brought her down in a wrinkled lame dress in a bathtub, and they had her in greasepaint without any powder over, so she looked like a grease ball. I later taught Mario how to use powder. A fabulous queen. But you know how much Miss Montez has been paid for all the films she did for Andy Warhol? A total of $110. That is usury.

But back to another usurer, the Flawless Sabrina. She said it was a sold out house and we couldn’t even get any comps. When I looked through the curtains, about a fifth of the orchestra was filled, so I quick asked the secretary how we were going to get paid. “In checks,” she said. Well, I went to my sisters from the Jewel Box Revue and said, “Girls, this looks serious. They’re going to pay us in checks.” Fortunately, we demanded on the spot cash from the Flawless Sabrina. Mario has still never been paid a cent for that show.

By 1965, after my celluloid career, I had had a nervous stomach for a dozen years, mostly because I was in show business. Where was I going to work next? Where was the money going to come from? I was going to emigrate to Morocco with my friend the Professor. We thought we could both live off his GI bill. And then I took acid.

I was sitting here in the parlor with a couple boys like you and in came a man I knew who was a real sad sack, a non compes mentis, “the worst thing on Christopher Street,” he is now called. But on this day, his lowness came in and his eyes were all lit up and he’s so vivacious. “I took LSD 25,” he said. “Lead me to it” I said. “If it can do that for you, it can make me a genius.”

So I took a trip and my nervous stomach cleared up. On that trip I said to myself, “Kid, all your life jobs have been dying out from under you. Burlesque. Vaudeville. Nightclubs. Everything died out.” And I said, “Why go to Morocco? Morocco has come to me.” See, you’d go over to the Casbah — that’s what I call the section of Tompkins Square — and you’d think you were in Morocco. All these hippies and these freaky fabulous people.

That was 1965 and to me, honey, the hippies were a Renaissance. There was never anything in my experience like them — it was the only period that I lived through that I identify with good art. I felt like all my life I had been waiting for the hippies to come along. It was the only time I was ever in style — I had always been 10 years ahead and 20 years behind.

It was Billy Bike that first told me about the Gay Liberation Front. He said, “You must come.” Another friend of mine said, “Oh, don’t go there — there’s nothing but dirty old men: they want it for nothing.” Well, there were a few dirty young men, but very few old ones. There were more lezzies mixed in with the fairies in the GLF than any other group. It was lovely, I never went to the meetings much — I could never figure out when to talk and I was always out of turn.

That wasn’t so true in the GLF as it was in GAA. When GAA took over, Mary, gay liberation started getting very straight, talking about Robert’s Rules of Order. I remember Sylvia Rivera who founded STAR — Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries. She was always trying to say things — the same kinds of things Marcia P. Johnson says in a sweeter way — and they treated her like garbage. If that’s what “order” is, haven’t we had enough?

Gay liberation was natural for me because I was a hippy. It was much tougher for the ribbon clerks, the straight life ones, because they had to live a double life. But, after acid and after the hippies, it was easy for me.

Читать дальше