However, Massino’s rehabilitation was engineered, it must have been done at Court level. Those with access to the Tsar’s immediate circle would have included ministers, high-ranking military officials and Rasputin. The Tsar’s former ministers and their fabled misdemeanours were a particular target for the Provisional Government which came to power after the Tsar’s abdication in March 1917. One of its first acts was to set up, in March of that year, ‘The Extraordinary Commission of Enquiry for the Investigation of Illegal Acts by Ministers and Other Responsible Persons’. One of the principal areas for investigation was Rasputin and the influence he had on ministers and the Royal family. The enquiry also had access to the Ochrana reports which catalogued the comings and goings at Rasputin’s apartment and a general digest of those he met. Although the commission’s investigations were still in progress at the time of the Bolshevik takeover in October, the new government disbanded the commission and its conclusions were never published. 25However, the enquiry’s transcripts survived and provide a rare insight into the activities of those in high places. It would seem that statements from some twenty-two people associated with Rasputin were taken, which provides a vivid picture of the influence he wielded at the Royal Court.

Alexei Filippov, a banker and publisher, provided interesting testimony as to how some of those within Rasputin’s close circle exploited the influence he had with the Tsar and Tsarina by accepting ‘gifts’ from those whose interests were forwarded by Rasputin. Whether this was with or without Rasputin’s knowledge is not clear. In 1906 and 1907, Rasputin’s connections with the Court were not so well known as they became in later years, but it is interesting to note that the person who first introduced Rasputin to those of influence in St Petersburg was Bishop Feofan, who was born in Poltava. He himself had very close royal connections, particularly to the Tsarina, and is another possible link between the Massinos and the Royal Court.

Filippov himself had very close associations with Rasputin and became the semi-literate peasant’s publisher. Some six years after Col. Massino’s re-instatement, there is also evidence that Rasputin’s aide Sophia Volynskaya had links with Varvara Massino, who like herself was a converted Jew from Poltava. Filippov told the 1917 enquiry that Rasputin shifted from charitable acts of help to the exploitation of clients with the help of Volynskaya. Her husband, an agronomist, had been tried and imprisoned, but had been pardoned on representations from Rasputin. Rasputin, however, justified these acts as part of his teaching. The Tsarina had written down his words in her notebook, ‘Never fear to release prisoners, to restore sinners to a life of righteousness… Prisoners… become through their sufferings in the eyes of God – nobler then we’. 26

Another Rasputin acolyte, Pyotr Badmaev, may also have had a connection with Reilly, according to Richard Deacon. 27Badmaev, known as the ‘cunning Chinaman’, was a doctor in Tibetan medicine, or so he claimed. In reality he was, like Reilly, a cross between a patent medicine salesman and a businessman- cum-broker. A Buryat of Asiatic descent, Badmaev was born in Siberia in 1857. His brother had established a Tibetan pharmacy in St Petersburg, and Pyotr followed him to the capital and soon established himself practising Tibetan medicine. His patients were predominantly in the upper echelons of St Petersburg society and, thanks to Rasputin, his influence permeated to the very top. He established a trading company, Badmaev & Ko, which was involved in land speculation and also sought to market a range of commodities including his Tibetan herbal remedies. These claimed to treat such complaints as pulmonary disease, neurasthenia, venereal disease and impotence. It is significant that while most patent medicine companies in England at this time promoted home-grown remedies or those imported from America, the Ozone Preparations Company was unique in having amongst its stock ‘Tibetan Remedies’. 28

The banker and publisher Alexei Filippov, as well as having associations with Rasputin, also knew Vladimir Krymov, the accountant of the Suvorin family, the proprietors of the Novoe Vremia newspaper. Krymov, who had power of attorney from Alexei Suvorin due to Suvorin’s ill health, was closely involved in the affairs of the family, from which perspective he provides an interesting insight into Reilly’s life during the period 1910–1914. Krymov relates how Reilly visited the newspaper’s editorial office nearly every day and was treated by the staff there as ‘one of their own’. 29Reilly’s ability to network and keep his ear to the ground was obviously well recognised by editor Mikhail Suvorin and utilised accordingly.

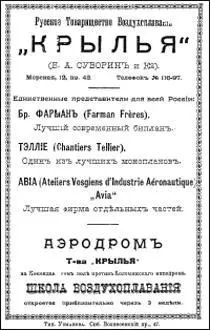

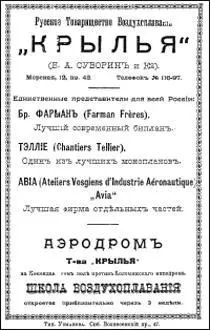

Mikhail’s younger brother Boris shared Reilly’s interest in aviation. According to Robin Bruce Lockhart they formed a flying club called The Wings Aviation Club, 30which sponsored the St Petersburg–Moscow Air Race. 31The reality, however, was somewhat different. Although Reilly was a member of a flying club, the All-Russian Aviation Club, 32Krylia (Wings) was, in fact, a commercial company set up principally by Boris Suvorin, at Reilly’s instigation. In other words, it was Reilly’s idea but Suvorin’s money was used to launch it. The Krylia Joint-Stock Company opened for business at Apartment 42, 12 Bolshaya Morskaya on 21 April 1910, amid a flurry of interest from the press, aviators and central government. 33The Ministry for the Interior in particular seems to have taken a close interest in the company, requesting that the Ochrana make routine enquiries into the five directors of the company – Frenchman Ludovic Arno, Mikhail Efimov, Boris Suvorin, Konstantin Veygelin and ‘Englishman’ Sidney Reilly. 34All five were given a clean bill of health by the Ochrana, which would seem to indicate that up to this point they had nothing on Reilly and furthermore did not identify or associate him with one Sigmund Rosenblum who was still on their ‘wanted list’. Such official interest might also reflect the fact that the Russian government was now taking a particular interest in the development of aviation for military purposes. In fact, Tsar Nicholas had, only a few months before, announced the creation of the Imperial Russian Air Service under the command of Grand Duke Alexandr Mikhailovich.

Advertisement in Vozdukhoplavatel announcing the opening of the Krylia Aerodrome in September 1910 another Reilly project financed by other people’s money.

Suvorin invited the famous Russian aviator Nikolai Evgrafovich Popov to open the office, and arranged for the event to be exclusively covered by Novoe Vremia. The company was the first to commercially market aircraft in Russia. Reilly’s interest in aviation had apparently been kindled by Wilbur Wright’s demonstration of the ‘Wright Flyer’ at the Hunaudières Racecourse at Le Mans in August 1908. The Wrights had, by this time, concluded that there was more to be gained from displaying their machines in public than from continued secrecy. It is clear from the European press at the time that there was certainly widespread scepticism concerning the merits of the Wright aircraft owing to their publicity-shy reputation. This attitude changed dramatically when Wilbur Wright arrived in France three months before the Le Mans demonstration and began touting the merits of the 1905 ‘Flyer’, a machine capable of flying up to twenty-five miles at a time when Henry Farman was endeavouring to achieve one kilometre in his Voisin.

Читать дальше