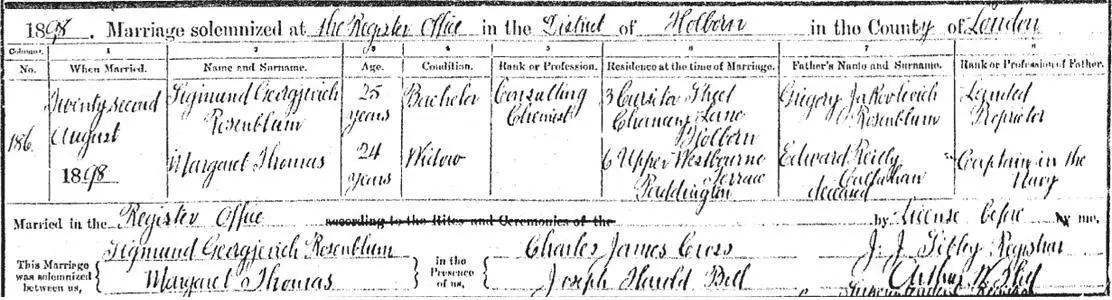

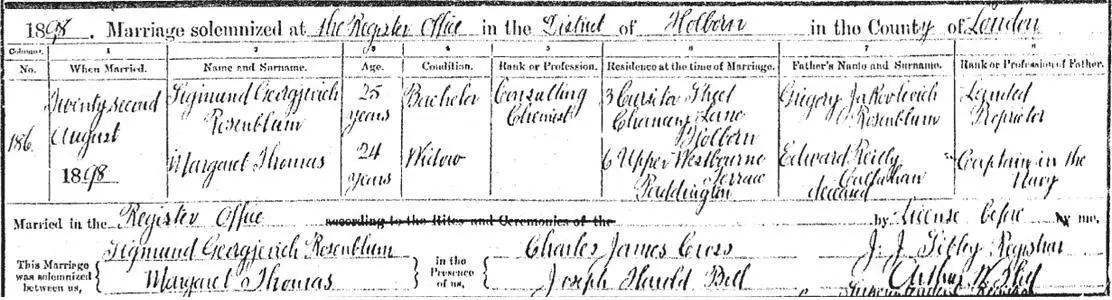

This would have been useless to Rosenblum as it would indicate quite clearly to anyone examining it that he had previously been a citizen of another country and was not British by birth. Furthermore, by adopting this approach, the passport would have been issued under the name Rosenblum, which again would have defeated the whole object of seeking a new identity. Rosenblum therefore needed a British passport in a new name, indicating the holder to have been born in Britain. Obtaining such a passport was motivated purely by the need to provide a new identity in Russia or in Russian-held territory. Although returning to Russia had been on his mind for some while, he certainly had every intention of retaining his British connections and wished, in due course, to adopt the Reilly identity legi-timately under English law by Deed Poll. This was why Margaret included the name Reilly on their marriage record. Should the question ever be raised in the future as to why they wished to adopt the name Reilly, they could fall back on the claim that it was her father’s name and produce the marriage certificate. It was not unusual for Jews either to anglicise their surnames or to change them completely. The story that it came from his father-in-law was therefore a justification or validation for using the name Reilly, not the origin of it.

Sigmund Rosenblum married Margaret Thomas five months after her husband’s sudden death.

In terms of manufacturing a new identity, who better to assist than William Melville? Prior to Sigmund and Margaret’s marriage, Melville had found a suitable Irish identity for Rosenblum to use – Sidney Reilly. A comprehensive search through Irish records of birth from their inception in 1864 (when the civil registration of births, deaths and marriages began in Ireland) found only one Sidney Reilly in the whole of Ireland. 77Interestingly, the child died soon after birth. More intriguingly, research conducted during the spring of 2003 into the family tree of William Melville revealed that his first wife Catherine’s maiden name was Reilly. According to family records, her father came from the same Mayo village as Michael Reilly, the father of the deceased infant Sidney. 78The provision of a new identity was not something Melville would have provided for any common-or-garden informer who was simply supplying émigr? ‘tittle-tattle’.

In late August 1898, according to Margaret, Sigmund went to Spain for an unspecified period, well supplied with money. 79Spain was a major terrorist centre during the 1890s and had witnessed a number of notable outrages. The previous August the Spanish Prime Minister, Canovas del Castillo, had been assassinated in Santa Agueda by the anarchist Angiolillo and in July 1896 twelve people had been killed in a bomb explosion in Barcelona. The Spanish government had made specific proposals to the British government for closer police co-operation to combat anarchism and had also referred a number of requests for action or further investigation to Melville through the appropriate diplomatic channels. 80

While Sigmund was away in Spain, Margaret ‘liquidated’ the Manor House in Kingsbury. 81Initially acquired as an out-of-town retreat for Hugh Thomas, the house was now surplus to their requirements. On his return from Spain, Sigmund settled into a life of leisure at 6 Upper Westbourne Terrace, Paddington, typically giving the address a more prestigious tone by re-styling it 6 Upper Westbourne Terrace, Hyde Park, London. 82Ever the gambler, he also took to horse racing (apparently with disastrous consequences) and set about enlarging his collection of objets d’art, at Margaret’s expense. 83Robin Bruce Lockhart has stated that within a few months of their marriage, Margaret sold 6 Upper Westbourne Terrace, putting the proceeds into a joint bank account and together they moved to St Ermin’s Chambers in Caxton Street, Westminster. 84The house was the property of the church commissioners, from whom Hugh Thomas had leased it since 1891, and Margaret could not possibly have sold it. Church records show that the Rosenblums moved out of the property in June 1899 and that a new lease was given to the incoming tenant, Ormonde Crosse. 85

Rather than heading for the bright lights of Westminster, documentary evidence strongly suggests an alternative scenario. According to Foreign Office passport records, a passport was issued in the name of S.G. Reilly on 2 June 1899, shortly before their departure from Upper Westbourne Terrace. 86Margaret also alluded to the issuing of a passport in a meeting she had in Brussels with the British vice-consul on 29 May 1931 when she was attempting to renew her current passport. 87According to the minute of the meeting, she stated that a passport had been issued in the name of ‘Sidney Reilly and wife’ in 1901. Study of the original document clearly suggests that the officials considering the matter questioned this claim. The date 1901 has been underlined and a question mark placed by it. This scepticism is born out by an examination of Foreign Office passport records that indicate the only passport issued to an S.G. Reilly between 1898 and 1903 was on 2 June 1899 (No. 38371). Although the 1899 register does not refer to Margaret, she may have travelled with him on the same document. Prior to the British Nationality and Status of Aliens Act 1914, passports were single sheets of paper, without photographs, and were issued for single journeys. It was common practice for a wife travelling with her husband to have her name entered on a passport issued under her husband’s name.

The consensus of other Reilly writers is that they left England for the Far East between 1900 and 1902. Michael Kettle places their departure ‘about 1900’, 88whereas Robin Bruce Lockhart has Reilly playing a role in Holland in the Boer War, spying on Dutch aid bound for South Africa. When the Boer War ended in 1902, Lockhart states, Reilly was sent to Persia to report on the possibilities of oil exploration in the area, and was eventually sent to Port Arthur in Manchuria around 1903. He also writes that Margaret stayed in England 89while Reilly was away on these missions, taking to drink in his absence. Jay Robert Nash makes similar claims to Lockhart in terms of missions in Holland and Persia, although he asserts that Reilly was at this time in the employ of NID, the Naval Intelligence Department. 90

While Margaret’s own recollections refer to proceeding to China in 1901, 91this does not necessarily imply they went directly from England to China. Although she does not give a specific date for the liquidation of the Manor House in Kingsbury, we know that this occurred after August 1898. Her account also claims that following the liquidation Reilly wished to return to Russia due to ‘homesickness’, and that in 1901 they changed their name to Reilly 92and proceeded to China. It therefore follows that they left England in June 1899 for Russia, and thence to China.

The timing of their departure from these shores was opportune to say the least, as they left at the very same time as a top-level Russian investigation was in progress in London. On 17 April, Petr Rachkovsky, chief of the Paris Ochrana, had written to William Melville at Scotland Yard seeking information concerning individuals residing in London who were ‘without any doubt’ involved in a massive rouble-counterfeiting ring operating in London. He concluded by:

…warmly recommending my friend Mr Gredinger, Deputy State Prosecutor in St Petersburg, who is leaving for London tomorrow, with the aim of taking charge of this case. It would be much appreciated if you could help Mr Gredinger out with whatever he might need and do everything in your power to make his job easier. My friend, will refund you… all of the costs which you have incurred in collecting information. 93

Читать дальше