I recalled what I could of Russia.

I was afraid to see it. I knew I was, too. Shouldn’t some things remain a memory? I thought so. Memory is so kind. I had no regrets. I left too young to have regrets. I had not left love behind, or friendship. We left family behind, but many were now with us in America. My father saw to that. Because of his extraordinary effort in getting himself, my mother and me out, four other families were delivered into Florida and Maine and North Carolina and New York: my grandparents, my father’s brother and his family, my father’s oldest friend and his family, and the oldest friend’s son and his family. He gave them all an American life.

But we still knew many in Russia who could not come, or would not.

I don’t want to go, but I know I need to see it with my own eyes. My grown eyes. It’s like gawking at an old boyfriend: how is he? You hope he is well, but not better than you. I wanted Russia to be well.

To see Shepelevo again was going to be worth the whole trip.

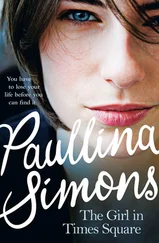

So much of my Bronze Horseman story was still a vapor to me. I hoped being with my father would not crush my muse, for when the muse comes, your heart has to be open to receive it. Maybe I would have some time alone to think, to write. We weren’t planning to spend every minute of every day together, were we?

When we first came to America, I knew little about it, except that there were sharks and they ate people. That I learned in school.

The Americans killed their presidents, and the sharks ate the Americans.

When my father had told me that we were going to be leaving Russia and going to America, the first question I asked him was, “Will the sharks eat us?”

“No,” he said. “They won’t.”

The second question I asked him was, “Do you think we will ever come back?”

He looked at me for a long time before he answered. “Never,” he said with sadness. We were walking down Nevsky Prospekt and as always he held my hand.

“Maybe when there are no more communists?”

He shook his head. “Not in my lifetime,” he replied. “Not in yours either.”

Yet, here we both were, proving him wrong. My father isn’t wrong about many things.

It was true, when we were leaving in 1973, that the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics seemed an all powerful monolith designed only to perpetuate the power of the Communist Party, fourteen million members strong, and to subjugate the rest of us. We could choose to become Communists if we wanted to. We could become Pioneers in third grade, then we could become Comsomols or young Communists in tenth, and afterward we could get a party card. A party card meant you could get into all the best stores.

Since the rest of us couldn’t get crap in any stores at all, party membership seemed pretty appealing.

Yet, even then, knowing nothing, the day I spat at a statue of Lenin when I was 8, I knew I would not make a very good communist.

After Mikhail Gorbachev came to power, and perestroika became the mantra of the land, the rules were relaxed a little.

My mother made an unprecedented trip to Russia in 1987 to visit her dying father. The fact that my mother went back all by herself astounded everyone in the family. My father had been afraid to go with her. He must have thought perestroika or no, the communists would throw him back to the labor camp and not be as kind this time.

So she went by herself, and then the Berlin Wall came down two years later. After the wall fell, my father, for all his protestations, made a trip to Russia. Then my father’s friend Anatoly visited us on Long Island, and then my Uncle Misha from Moscow came, and finally in 1994, my mother and father went to Russia together for the 50-year celebration at my father’s alma mater. My father was invited as an honored guest, a man who had left Russia and made a great success of himself.

I am not saying that all these events transpired because of something my mother did in 1987, but I can’t rule it out.

If there is one question I am always asked after I say that I was born in Russia, it is, “Have you been back?”

During Communist rule, my answer was always a puzzled, “Of course not.”

But after 1991, the simple “No,” became infinitely more complicated. There were children involved to be sure, and a sense of danger, of unstable economic and political times, of — as always — logistical issues, but most of all, it was the question of me: why would I go back? What was in it for me? What would it profit me to go back? What was the point?

I was happier thinking I would never go back.

There was a certain romanticism in being that kind of outcast. A refugee for life. Woman leaves as a young child, childhood memories intact and having already shaped her development, and then she carries Russia with her in her soul, but never again sees the place where she was born and grew up. Such melodrama!

That was one of the reasons I was reluctant to go back. To me going back felt like capitulation. Like I wasn’t going to appear as delightfully melancholy.

But now it was for a greater good. It was for my book. Finally a book about Russia, and about a time and place during WWII few people talk about or know about.

I had to see the Leningrad streets. I had to see where my two lovers walked, where they fell in love and said their goodbyes, and where my soldier fought against a mortal enemy, and against the Nazis, too. I had to see the streets where people starved to death by the thousands.

I had to see the city where I was born.

Clearly I am not comfortable with it. My first three books are all close to my heart, but not thatclose . I liked to bare my Russian soul, so long as I didn’t have to bare it about Russia.

Also. I really had no interest in getting in touch with my sensitive Russian side. During my adolescence, what I would not have given to be less Russian, less foreign, less un-cool. I wanted a pair of new jeans, I wanted American hair, which meant hair not cut at home by my mother. I wanted coats that were not knit by my mother. What humiliation, no matter how well-meant.

I wanted to be able to speak the language of the hip kids in school, I wanted to be able to say “Hi,” in English without sounding like a dork.

As I grew, I carried with me the feeling of wanting to be an American wherever I went.

I went to England. I was twenty.

The English, smiling their sly, sardonic British smiles at me would ask, “So… wher’ you from?”

“New York,” I’d say.

Those smiles again. “Really? We never would have guessed.”

They thought they were being so clever in mocking me. “What have Americans ever given us?” they’d say. “Except McDonald’s and herpes?”

I thought I couldn’t have been luckier. To the British I wasn’t Russian, I was American. It took five years of my living in London for me to become an American. In England, I was not from Russia anymore. I was from NooYawk.

But despite my best efforts, I knew I was only an American on the surface. I knew that I could make a really good show of it, get a nice American haircut, buy nice American shoes, and a pair of Levi’s. I could drive a Chrysler minivan, and even learn a word like equivocate and use it in a sentence.

Regardless of what the English thought, my soul was painfully Russian. It was Russian music that brought tears to my eyes, and Russian food that made me fullest, and Russian language that made me feel as if I were home.

Having turned myself inside out to become what I was not, inside I still craved pumpernickel bread with sunflower oil and fried potatoes with onions.

For twenty five years, I tried to put away the child part that was Russia, but now I was being called home.

Читать дальше