“I’m not sure they’ll work with all this racket,” I said.

“You’ll get used to it,” Marta told me. I did not. Sleep was impossible, even with earplugs. At 2 a.m. I booted up my laptop and began work on assignments from my Toronto job.

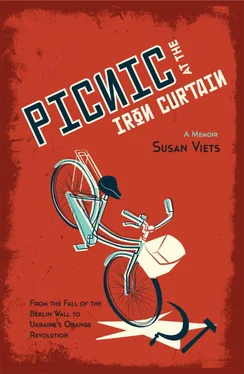

During the day, Marta and I wandered. The Orange Revolution, headquartered on Khreshchatyk and in the square, reached far beyond these hubs, to all the main government and presidential offices. We walked up a cobblestone hill, toward the presidential administration. We passed a group of young guys dressed in orange smocks made from garbage bags. The hip-hop anthem of the revolution, “Together we are many; they will not defeat us,” blared from their boom box. The music trailed behind us, then faded away as we turned right onto Bankova Street and saw riot police, who stood two rows deep. For several days protesters had blockaded ministerial and presidential offices, forcing the administration to work in exile from the outskirts of the city. These riot police had only recently arrived and now controlled the streets around the presidential administration, though the administration had not returned to Kiev.

I knew this neighbourhood well. A small pedestrian path down an embankment, just beyond where the riot police stood, led to my old address. I still thought of it as Karl Marx Street, even though it had been renamed Vulytsia Horodets’koho some time ago. I had wandered here on evening walks and admired the stately architecture, much of which pre-dated the 1917 revolution, when sugar barons lived in Kiev. Beyond the rows of riot police, I could see Horodetsky House, its art nouveau facade strewn with fantastic animal scenes, and the imposing white columned presidential administration across the street, the old Communist Party headquarters, where I had watched looters inside after Ukraine declared independence.

I thought again of Yushchenko’s speech and his appeal to officers. I wondered about the possibility of conflict. The police kept their helmet visors up and their shields down, which was a good sign, for now. Three young women crossed a no man’s land that separated bystanders like us and protesters from the police. The women held bright bouquets. They handed the flowers to the police officers.

“What did they say?” I asked Marta.

“They’re begging the riot police not to harm anyone in the crowd.” Orange balloons bobbed above the police barrier, held in place with shiny ribbon. Candles, flames flickering, stood on the pavement in front.

We strolled past tents pitched by the sidewalk and saw empty oil drums with fires inside that kept people warm. The Writer’s Union across the road, an elegant yellow low-rise with a soup truck parked in front, was another headquarters for the Orange Revolution. Marta and I walked inside. Protesters in orange packed the ground-floor hallway. We followed a sign for the medical centre. Doctors wore plastic name tags. Garbage bags ringed the perimeter of the room. Donated clothes tumbled from the overstuffed bags.

“Do you need anything?” Marta asked one of the doctors.

“We have all this,” the doctor said as he pointed at the bags of clothes, “but our medical supplies are low.” Marta pulled out her notebook. The doctor dictated the names of drugs to buy — antibiotics, eye drops and many more things that I could not identify with my limited vocabulary.

We left the Writer’s Union and walked down the road to a pharmacy. Its shelves spilled over with products. I read labels as Marta ordered stock. For thirty dollars we emerged with a bulging bag of medicine. I found it odd that nothing, not even antibiotics, required a prescription.

We returned to the medical centre at the Writer’s Union and gave a doctor our bag of medicine. As we left, we passed by a staircase. People wrapped in blankets slept across every step — overflow from the designated first-floor rest area. When I looked in that room, I saw a sea of slumberers and no unoccupied chair. Sleeping bags and pillows blanketed the stage. Those who found no space on the stage lay on the floor.

We continued our walk. We took a back route, down a hill, to the top of Vulytsia Horodets’koho, crossed through a small park at the end of the street and climbed the footpath that led toward the president’s office. At the top of the path, we encountered more riot police, grim-faced, clutching truncheons, in no mood to talk. Admitting defeat — we would not get closer to the building than this — we hovered for a few minutes, then went back down the path. We stopped briefly, riveted by a news broadcast on a small television. Several large-screen TVs, professionally installed, stood at strategic points in the city centre to keep protesters well informed of the news. This small black and white TV was not one of them. It balanced precariously on a metal structure. Wet snow fell. I felt amazed that no one had been electrocuted changing channels.

Yushchenko’s rival and the man backed by the regime, Viktor Yanukovych, appeared now on TV. The program showed clips from a big meeting of his supporters in southeastern Ukraine, who threatened secession from Ukraine. One of the announcers said Yanukovych’s wife, Ludmila, had addressed a rally of anti–Orange Revolution people outside. She said that Yushchenko supporters in the square in Kiev were so happy because they had eaten oranges imported from the U.S. laced with hallucinatory drugs.

People who stood near us gossiped about Mr. and Mrs. Yanukovych. I heard that Yanukovych had been jailed twice, for assault and then theft; Ludmila used to drive a trolleybus and Yanukovych, in the 1970s, drove racing cars in Monte Carlo; on their first date, a brick fell on Ludmila’s head, Yanukovych rushed her to hospital and then proposed. I had no idea if any of this was true. All I knew was that they managed to stay married all those years. I had not.

In the evenings, I met with friends and caught up on their news. So many of my female friends were either thinking about divorce, in the middle of divorce, already divorced or single. I tried to tease wisdom from this observation but did not get far. We all loved to travel and had all worked as journalists, but the similarities in our circumstances ended there. I noticed some gender divide. Stephen, Yaroslav and James all remained married. I discussed this with Marta. Then, as always, with so much going on, our conversation drifted back to politics. The phone rang.

“It’s for you,” Marta said and handed me the receiver.

“Hi, it’s me,” Yaroslav said. “What are you doing for dinner?”

“Marta’s busy, but I’m free,” I told him. We arranged to meet at Yaroslav’s hotel. A few minutes later Stephen telephoned. I invited him along.

I felt that I was walking into my past as I climbed the hill to meet Yaroslav. He was staying in an old Communist Party hotel where we had often eaten in 1990. Few other restaurants existed then in Kiev. I wondered how Yaroslav felt lodged in this hotel, like a visitor in his own home city. His life was so different from when he left.

I reached the hotel around 9 p.m. and rode up in the elevator with a man in his late thirties or early forties, who wore a bright orange down jacket. Heavy stubble covered his cheeks and chin. He had a scruffy air of authority.

Stephen arrived not long after me. We waited in Yaroslav’s room while he filed his story. He spoke with his editor. I remembered this work rhythm so well and that sense of satisfaction with a story filed, the work day finished and dinner deserved. Much as I enjoyed reporting, I did not feel tempted to make this my life again. I still thought of my office in Toronto, worked on assignments for it and found time for writing to family, colleagues and friends back home.

When Yaroslav had finished, we took the elevator down to the hotel restaurant. This cavernous room was mostly empty. People crowded around one long table at the far end. I recognized Volodymyr Filenko, a Member of Parliament and behind-the-scenes organizer for the Orange Revolution. The man with the orange jacket and a heavy-set male companion occupied another table. We sat at a table next to them. A few minutes later Stephen said, “Look, it’s Yulia.”

Читать дальше