By now Kane’s one folder had grown to many carefully put-together files, all contained in a large brown cardboard box. For two days Bob Carroll pored over Kane’s files, more and more amazed—stunned, actually—at what the young detective had single-handedly put together. “It was,” he would later say, “one of the most significant, incredible files I’d ever seen.”

Thus the New Jersey attorney general’s office lined up behind the investigation that Detective Pat Kane had started.

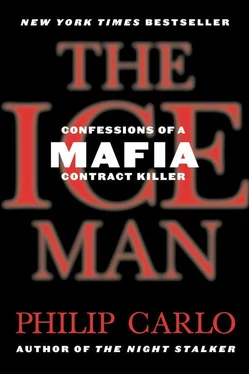

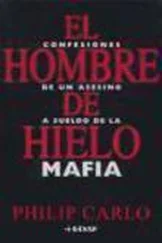

On the evening of September 6, 1986—four days after Dominick Polifrone had his first meeting with Kuklinski—Pat Kane sat down in a windowless war room in the New Jersey attorney general’s Fairfield building. He was surrounded by law-enforcement heavies, including Bob Carroll, Deputy State Police Chief Bob Buccino, Captain John Leck, and New Jersey Organized Crime and Racketeering Bureau investigators Paul Smith and Ron Donahue, all interested, all there because of Kane’s diligence. No one doubted any longer what he’d been saying. If John Leck was also there, he was now behind Pat Kane 100 percent. Here Operation Ice Man—because they believed Richard had frozen Masgay—was formed, and the rope to hang Richard Kuklinski became longer still.

Over Chinese takeout, Pat Kane and Bob Carroll carefully laid out all the information Kane had gathered over the many months he’d been working the case: how it all began as a series of unsolved burglaries; the murders of Masgay, Smith, and Deppner, and the disappearance of Hoffman; Kuklinski’s connection to Roy DeMeo and organized crime. All that Kane had found out, put together, was tremendously helpful. But the attorney general’s office needed tangible evidence that would hold up under the withering scrutiny of a crack defense attorney.

Dominick Polifrone was the answer. They would use him to get Kuklinski to incriminate himself. If Kuklinski had asked Polifrone for cyanide at their very first meeting at the Dunkin’ Donuts, it stood to reason that Polifrone was “in,” that Kuklinski would hang himself.

Cyanide was the key—that would be the beam from which to hang the rope.

With permission from his superiors, Polifrone soon attended a second meeting of the Operation Ice Man task force, and Bob Carroll ran down for Polifrone what he wanted. Again present were Pat Kane and the heavies—Investigators Paul Smith and Ron Donahue, Deputy Chief Bob Buccino, and Captain John Leck. Ron Donahue was a seasoned, hardened investigator, notorious for his toughness on the streets. He was actually booed by mob guys when he showed up in court, walked into mob hangouts. He very much looked like the boxer Jack Dempsey and was tough like him. Paul Smith was in his early thirties, had a Beatle haircut, hooded dark eyes. He was an adept undercover guy. Only Captain Leck wore a uniform. Bob Buccino had a thick head of silver hair, was a patient, intelligent man, a good administrator, adept at getting people to work well together. They all sat down. Now there was an eight-by-ten glossy of Kuklinski taped to the wall, a bull’s-eye drawn on it.

Bob Carroll began: “Dom, at this point the key is the cyanide; see if you can get him to talk more about it—how it works, how long it takes, could it really be used to fool a medical examiner. Details. Get him to talk about details, other victims.”

“I know exactly what you want, and I’ll get it,” Polifrone said. They all knew that Polifrone was the man for the job. It was obvious to everyone there that Polifrone knew the walk and knew the talk.

“The problem is,” Polifrone said, “he already beeped me, and I called him back, and he really wants the cyanide.”

“Yeah, well under no circumstances can we give him cyanide,” Captain Leck said. “Just think about the ramifications if he uses it to kill someone.”

“I’m only going to be able to stall him so long. I mean, if he doesn’t get it from me, he’ll get it somewhere else, and I might very well lose him. Right now the cyanide is the hook, line, and sinker.”

“You’ve got a point,” Carroll said, and they discussed the pros and cons of providing real cyanide to Richard, but in the end that idea was shot down. There was no way that they could give Richard Kuklinski cyanide.

Bob Carroll said, “Stall him, just keep stalling him, all the while getting him to talk. I think he believes he’s above the law at this point, that he’ll never get caught, and we’ll use that against him.”

They now discussed the fact that someone had spiked a Lipton soup packet with cyanide in a grocery store in Camden (not Richard), and a Jersey man had bought the soup, eaten it, and died. It was a big news item, and Polifrone said he could use this as an excuse to stall Richard. As they were talking, Polifrone’s beeper sounded; amazingly, it was actually Richard. Captain Leck wanted Polifrone to call him right back.

“Let ’im stew a little bit,” Polifrone said. “I don’t want to, you know, seem too anxious.”

“Agent Polifrone, your target called, call him back!” the captain insisted.

Polifrone repeated what he’d said. Of course he was right. It seemed, however, that Leck wanted to get into a pissing contest with the ATF agent. Finally, Carroll had to step in and tell the captain that Polifrone would decide how to work this.

“Who’s running this investigation, us or the ATF?!” the captain demanded.

“This,” Carroll said, “is a joint operation, and I have every confidence in Dominick’s expertise.” Captain Leck had to accept that. He stared at Dominick as if he wanted to take a bite out of him.

This was, Dominick had known all along, one of the biggest problems with interagency cooperation, or actually the lack of it: everyone wanted to be the boss, everyone wanted the glory. No matter what this uniformed stiff said, though, Polifrone was going to work this case the way he saw fit. It was his ass on the line, not Leck’s. It didn’t seem like a good match, but he’d do whatever he could to make it work.

Now, based on Polifrone’s initial contact with Kuklinski, Carroll planned to get warrants to tap all of Kuklinski’s phones, and an elaborate plan was put in place that would allow the calls to be legally recorded in a safe house near the Kuklinski home. Conversations would be listened to and transmitted into text by a team of typists in a second location. They had to catch every word accurately if these tapes were to be used in court. After they agreed on the nuts and bolts of this aspect of the operation, it was nearly 9:00 P.M., and now Dominick returned Kuklinski’s call. He had made him wait two hours.

Richard said he wanted to get together to discuss the arms deal, that he would bring his dealer and they could meet at the Vince Lombardi Service Area off the New Jersey Turnpike in Ridgefield. This caught Dominick off guard, first because Richard wanted to introduce him to his contact, and second because there wasn’t enough time to properly set up a comprehensive surveillance operation. If what Polifrone had heard about Kuklinski was true, and he had no reason to believe it wasn’t, Kuklinski was by far the most dangerous man he’d ever come up against, and he wanted to be sure all the ducks were lined up properly before he put himself on the line. What concerned Polifrone further was the fact that this was a joint, interagency operation. There was therefore no focal point of command—simply put, too many chefs in the kitchen. Polifrone had a wife he loved dearly, three children he was crazy about, and he wasn’t about to give that up by getting caught up and hurt in an interagency pissing contest.

Plus, Polifrone had no idea if Phil Solimene was playing two ends against the middle or was on the up-and-up. For all he knew, Solimene had been feeding Kuklinski information and setting him up. He had heard of much stranger things than that. When it came to mob guys, he knew, there was no telling what they’d do. They were dangerous, unpredictable jungle creatures, not creatures of habit, rhyme, or reason.

Читать дальше