I was alone in the office when the telephone rang. A Dutch male voice asked, “ Advertitie voor twee kamers?” Ya , I replied, not me (or may , as it would be pronounced in Dutch), my friends, twee persons voor twee kamers . I felt quite proud of myself, two people for two rooms. Aah , he said, twee persons. Ya , I said, do you have them? Twee kamers , he said. Ya, ya , I said. Slowly, and partially in English, he said, “I am holding my pemel .” Oh, ya , I said, thinking he might mean he was holding a pencil, not knowing the world for pencil in Dutch, though curious as to why he would tell me that at all. “ Momentje ,” he called out. I imagined he was writing something down and waited. “ Ik kom ,” he cried. I hung up.

It’s Independence Day, the Fourth of July, and America is 236 years old. I’ve been pondering the tortuous coupling, “art and politics.” Each partner resists easy definition, especially “art” (“Is it art?” and “What is art?” are jokes); I can’t imagine Ludwig Wittgenstein countenancing their murky conjunction. It’s hard to avoid the couple’s traps.

Art is not usually measured by its utility (the school of “relational aesthetics” attempts to call that hand), while politics is. What usefulness is believed to be is also a matter of contestation. In 1972, in Amsterdam, with artist Jos Schoffelen, I ran a cinema with an eclectic program, the first in the Netherlands to feature double-headers and to screen an Andy Warhol movie, Bike Boy (1967). A rogue film collector approached us with a 16mm print of Tarzan Escapes (1936). He screened it for us: Its white supremacy and brutal racism were shockingly casual. Black African men fell off steep cliffs, while their white British masters exclaimed about the loss of precious equipment.

Jos and I wanted to pair it with a documentary about the Black Panthers. Amsterdam’s Communist Film Club distributed it, but wouldn’t rent it unless we organized a protest march. “Why do we have to organize a march?” “Because it’s a political film,” they said. I said, “If people want to march afterward, they can.” Juxtaposing the two was art and politics; “Art could be a dialogue,” we said, “which is political activity.” “No way,” they said.

The cinema wasn’t considered “serious” because of its emphasis on art; soon their club vetoed the cinema getting funding from Amsterdam City Council. Maybe this is too strident or absurd an example of conflict between, and in, art and politics. Generally, I proffer the idea that all art is political, though I’m not satisfied by it. It seems subtle, yet too broad, and because of this not convincing. But I may be trapped in it, not having a better argument.

Writing novels and stories, I’ve become convinced that narratives concern themselves with justice or adjudication. Writing fiction, I might be able to avoid mental traps, habits of mind. I try to be vigilant about how I write — style, form — to trample complacency of all types; in concert with a writer’s lacks, it generates truisms and stereotypical characters.

I often recall other artists’ choices. Ad Reinhardt drew political cartoons and made non-referential paintings. The American poet George Oppen stopped writing poetry for 30 years, after he became a member of the Communist Party in the 1930s, because he wouldn’t write Party poems. When he started again, he produced an exceptional poetics.

In a performance I once saw, the artist Bob Flanagan hammered a nail into his penis. I put my head in my hands, covering my eyes (one man fainted); but I wouldn’t think of stopping him. It was his penis. Was this a political act? Flanagan was born with cystic fibrosis and was told he’d die at 20. He’d been a cystic fibrosis poster boy at 13. His art fought his genetic identity, and what the disease didn’t cruelly claim, he tormented. For his exhibition “Visiting Hours” at the New Museum, New York, in 1994, Flanagan built a hospital room and lay on a hospital bed, attached to an oxygen tank.

Viewing Flanagan installed as a piece in a museum, knowing him since the 1980s, I felt disorientated — installed momentarily in his hell. “Voyeuristic” pales as a description of my looking. Was his métier disorientation? Flanagan’s conflation of art, body and disease bewildered me, rebelling against any modifier, such as progressive or regressive, which might characterize the politics of an art practice.

Some say artists should make work for an audience, that anything else is indulgent; art should be “accessible.” To whom is never clear. Recently, in various newspapers and literary magazines, a debate about so-called “difficult books” has been unfolding. Writers should remember their readers, one side insisted, by making books enjoyable. For one thing, “difficulty” and “pleasure” are relative terms; without foundation, the argument lacked cogency and drifted into nowheresville.

Filmmaker Trinh T. Minh-ha reckoned with the concept of audience differently. Minh-ha was present at the New York premiere of Naked Spaces — Living is Round (1985), at the Museum of Modern Art. The film pictured women working, walking, socializing. No narrator explained the women or the spaces they inhabited. Instead, words shaped and suggested more impressions, ways of seeing.

The first question to Minh-ha came from a man, who asked, vehemently: “Who is this film for? Who’s the audience for this film?” Minh-ha took a moment, then said: “I make films for sensitive people.” Her audience fell silent, maybe stunned by her brilliant tactic, which leaped over patterned responses. Minh-ha allowed for the contemplation of positions, by escaping the usual discursive traps. It’s the hardest thing to do, and in art and politics the most imaginative and stimulating.

Stars In Their Eyes: Fame is a Frame

Life’s tough as a street-art puppeteer, but when Craig Schwartz (cunning John Cusack) starts a deadbeat day job in an office where the ceiling’s so low everyone has to bend over, he discovers a way out — a secret tunnel into the mind and body of John Malkovich (playing himself, sort of). Spike Jonze’s first feature Being John Malkovich renders identity as the playground and prison it is. When everyone wants to be known, rather than to try to know, celebrity is the pinnacle of success. To the star-obsessed, being known might mean not having to know yourself, and if you don’t like yourself, this must be freedom. Dropped into the body of someone else, though, might allow for the ironic discovery that others are just as limited as you are. I laugh every time I think of Cameron Diaz — so thoroughly unglamorous she’s a sight gag — in a cage with a monkey; and Malkovich at home halfnaked, his paunch smiling at the fantasy of celebrity perfection.

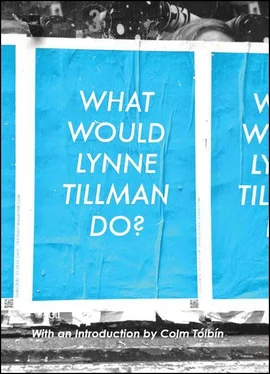

The publisher and author would like to acknowledge and thank Stephen Frailey, artist/photographer and chair of Undergraduate Photography Department (The School of Visual Arts), for providing the title for this collection. Frailey edits a photography magazine, Dear Dave , and for its advertising campaign, several years ago, chose to run, in every issue, a powder-blue page, with white letters: “WHAT WOULD LYNNE TILLMAN DO?” (This was a great surprise to LT.) On the side of the page, it says: Subscribe to Dear Dave, WWW.DEARDAVEMAGAZINE.COM. We heartily recommend you do.

Lynne Tillman is the author of five novels, four collections of short stories, one collection of essays and two other nonfiction books. She has collaborated often with artists and writes regularly on culture. Her novels include American Genius, A Comedy (2006), No Lease on Life (1997), a New York Times Notable Book of 1998 and a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award; Cast in Doubt (1992); Motion Sickness (1991); and Haunted Houses (1987). Someday This Will Be Funny (2012) is her most recent short story collection. Her nonfiction books include The Velvet Years: Warhol’s Factory 1965–1967 , with photographs by Stephen Shore (1995); Bookstore: The Life and Times of Jeannette Watson and Books & Co . (1999), a cultural history of a literary landmark, and The Broad Picture , an essay collection.

Читать дальше