Jim

DICK PALMQUIST

Trenarren Hotel

Greystones, County Wicklow

November 30, 1963

Dear Dick,

[…] I try to keep in touch with reality by listening to the Armed Forces Radio from Germany — spot announcements telling me to turn down my radio, to install seat belts, to give blood, and to drive carefully. I followed the terrible events in Texas for several days (AFN had access to all three networks in America), and now that it’s over, I still don’t understand it, and I guess that is as it should be, sound and fury signifying nothing. […]

It is late. AFN’s Mr Midnight, a very romantic fella, has gone to bed. The wife and family have gone to bed. The only ones up are me and the Germans (on the radio), who never seem to go to bed. And now I’m going to bed. […]

The following morning. Frosty today, for the first time, a harbinger of the cold-assed days ahead, as we say in the writing game. […]

The house we’ll be moving into is comparatively new (1933) and consequently is snugger than we’re used to in Ireland. It has several rooms that appear to be quite livable — not perhaps as you would use the term, or I, ideally, but by the standards that apply here, at least to our income and experience. […] Best to you both from us both.

Jim

JOE AND JODY O’CONNELL

Trenarren Hotel

Greystones, County Wicklow

Christmas Night 1963

Dear Friends,

Just because this letter comes to you mimeographed,12 do not think it does not come from the heart. Well, another year has almost ended, and once again, as I sit here before my fire (electric this year), my thoughts range back through the days gone by, gone but not forgotten. There was much to be thankful for, more than I have space for here, but here are some of the highlights that come immediately to mind. January and February, so far as I can tell from my diary, were taken up, as were the previous six or eight months, with correspondence with, and dark thoughts about, my publisher. March, as some of you may recall, was the month I won the National Book Award for Morte D’Urban , now available in paperback at 60¢, and went to New York City to be honored by the publishers, book manufacturers, booksellers, and gentle readers of America. Unworthy though I was, I could see no way out and tried to conduct myself like a good arthur and family man should, and in this I think I can say I did good. April passed without an award, but in May I went to Chicago, that toddlin’ town, for another. June was unsensational, as were July, August, and September until we kissed St Cloud goodbye. The rest you more or less know, and that brings us up to Christmas. I received the following gifts from members of my family: napkin ring (Mary); talcum powder, with built-in deodorant (Katherine); diary (Boz); socks (Hugh); pipe cleaners and clothes brush (Jane); and Drambuie (Betty).

The latter hit the hay at 8:45 p.m. tonight, which may be a new record, but then the poor kid carried the rest of us through the ordeal of Christmas, no little thing in our present circumstances.

We were very glad to get your letters, for which we waited and waited, which is not to say that we do not understand the many reasons for the delay. One you don’t mention, namely the busy and exciting life you lead. By our standards, I’m not kidding. NOTHING HAPPENS HERE. Well, yes, Boz did lean on a window in the lounge yesterday, and getting it repaired, or perhaps repairing it myself, may keep me occupied for days in this town, where nothing is easy, where a piece of glass 38" by 36" may mean a trip to the next town (Bray), and this on a bus, if you can picture us, me and the glass and probably a strong wind blowing. […]

The panel for George looks good under my magnifying glass — and all I can say against it is the medium, wood, which always has a way of looking wooden, particularly when new. Or so I think, and seem to recall you do. I pray it all ends well, with you and George, and I think it will. And right here I knock out ashes from a pipeful of #400, specially blended for Rev. Urban Roche, which I smoke on feast days and great occasions or would if there were any of the latter. I am down to about 4 oz. of #400 and two small packages of Brindley’s and have bought my first Irish tobacco at the going price of $1.40 for 2 oz. I am rationing out the other on those dark nights of the soul which come a bit oftener than formerly, as I take up the eternal subject of dirt, disrepair, folly, and waste with myself. […]

I loved “a heavily insured bag of nuts,” and Dickie should have used longer tacks.13 It’s all too easy to use short tacks and hit them harder, but where does it get you in the end? When I was a householder, and a goddamn good one too, I always kept a plentiful supply of tacks in assorted sizes. I checked my stock regularly to see that I wasn’t running low, and I also checked against rust spores, which have a way of getting into a nest of tacks, and if anything plays hell with tacks, it is rust. Keep plenty of tacks on hand at all times, and don’t let rust get to them lest there be hell to pay. Keep tacks on a high shelf, under lock and key, away from children. […]

We often think of you. I don’t know when we’ll go back to America, or where we’ll go when we do. We have literally no plans.

Jim

Epilogue: I once knew a writer (before I was married) who had a wife and four children, and he was always traveling around with them and his manuscript of the moment, which he kept in a metal file, which he carried, and when this writer came into a hotel dining room with his wife and children and the metal file and the violin case (one of the children played the violin), he’d turn on you in anger and say, “What’s everyone looking at?” That has since become the story of my life, except that I have five children (none of whom, however, plays the violin) and a leather case for my manuscript, and I don’t ask what everybody’s looking at.14

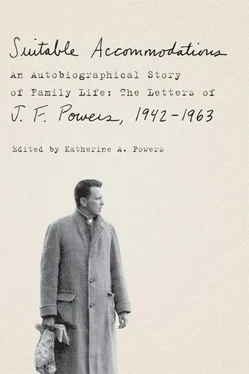

J. F. Powers, 1963

Afterword: Growing Up in This Story by Katherine A. Powers

Katherine Anne Powers

This volume ends with 1963. There are enough letters, further removals, and more ocean crossings en famille to supply at least another volume, but the novel Jim might have written concludes here. What lies ahead, years ahead to be sure, is a certain resignation. “It’s as if the story of my life has been badly cut, like a film, and what’s left has those specks and scratches on it from too many showings.”1 But what lies directly ahead — the near future, that is — is not suitable material for Jim’s gift.

His children were becoming adolescents and, infinitely worse to his way of thinking, teenagers. The presence all around him of burgeoning consciousnesses, of egos to rival his own, and, most harrowing, of his two older daughters’ growing fascination with the opposite sex was too much for this author to control and defuse through comedy. In 1963, he hadn’t yet come to see his children as people possessing identities and destinies separate from his own — that revelation was years away — but he was having trouble maintaining the illusion that his was the central point of view. Add to that the older children were beginning to be infected by popular culture, and not just any popular culture either, but that of what was becoming the sixties. This he viewed with appalled incredulity, and the move to Ireland in 1963 was made in part to stem the contagion. I cannot say that in this respect it was a roaring success.

Growing up in this family is not something I would care to do again. There was so much uncertainty, so much desperation about money, and so very little restraint on my parents’ part in letting their children know how precarious our existence was. Our terrible plight — as it was always painted — was made all the more so by how particular, not to say impossible, our requirements were in the realm of housing and style of living.

Читать дальше