Then we went to one of the faculty’s house and had one drink. It was rushed so I could catch the 11:59 train for Ann Arbor, which I did. I walked home, feeling I needed the air. Then I smoked a pipe here, thought I ought to set this sort of thing down in a journal but felt it was too much trouble, that I should say what I have to say in my work — and wondered, though, whether the journal, if I kept one, might not have a more lasting value even as literature. […]

Before I close, I want to say that there were some wonderful faces among the clergy there last night. One wonderful old man whom I’d been conscious of during the reading and questions came up and said I was too kind to the clergy, we’re worse than that, he said. This was nice but irrelevant to my real interest — which was in him himself, what a wonderful face, so round, the hair, so white, the eyes, so blue. I hated to think of him dying, as he would in a few years, all that perfection disappearing from the earth. All for now. It won’t be long now. Time is working for me now.

Much love,

Jim

19. This room is like a dirty bottle, but inside is vintage solitude, January 23, 1957–August 1, 1957

The Vossberg Building, suite 7

ROBERT LOWELL

509 First Avenue South

St Cloud, Minnesota

January 23, 1957

Dear Cal,

Every now and then I wonder whether you are a father yet. I hope there has been no difficulty about it, or that there will be none. I don’t see anyone who would be able to enlighten me. (Allen Tate, I heard, was in India, although last week there was a piece on him in a Mpls paper about the Bollingen prize.) I’d appreciate some word on this from you. Ordinarily, I take no interest in this sort of thing, which is so common hereabouts, but it’s different with you.

I returned from Ann Arbor last week, having completed my semester there. Things are getting back to normal, with me up all night and the temperature 15 below.

No doubt you saw that I am to be one of the Kenyon Review Fellows in Fiction. This is hard to explain, the honor of it, especially since I’ve never published there, and though I haven’t had it indicated to me in any way, I attribute this to Peter Taylor. It is a break, and it, with what I have contracted to extract from Doubleday in advance royalties when the need arises, assures me of two years of economic freedom. I’m hoping I’m old enough, finally, to make the most of it as a writer and not to fritter the time away as I have in the past.

I read Elizabeth’s story in The New Yorker last night and greatly enjoyed it.1 I hoped, when I finished it, that it was the beginning of a novel and wished — I always envy good work — I could command the academic scene, which does interest me as one of the few in which you can make some sense out of what happens in terms of the past and ideas and character.

I see Flannery O’Connor has won the O. Henry with her “Greenleaf” story. I dropped her a line from Michigan when I read the story last fall. I thought it was very fine, only regretted that she killed off Mrs May, such a waste and not necessary. I advised her to go on with those characters just as if Mrs May hadn’t died. She said that death was the great temptation after she’d written thirty pages about any of her people. I’ve heard this called the Irish temptation or “out,” and suppose she might’ve been referring to that. […]

Best to you both.

Jim

KATHERINE ANNE PORTER

509 First Avenue South

St Cloud, Minnesota

January 25, 1957

Dear Katherine Anne,

Your letter received this morning, and I hasten to clarify a thing or two. I decided I’d be wise to take the Kenyon, which is worth $4,000 to a married man. […] I am better off than I’ve been for a long time. Now I must watch myself: I have a great capacity for indolence, for lounging about. In Ireland you’ll find me at Leopardstown about this time of day (3:00 p.m.), with as much as ten shillings riding on a race. That is another thing I liked about Ireland. I could go to the races, to the theatre, eat out, and even buy books without feeling profligate. I have a gaudy feeling I don’t like whenever I do such things here. To do what comes naturally partakes of a spree here. […]

Our success, survival rather, has been due to the fact that we did without things, and we know we’ll do so again — and again. We know where we come in economically — that we don’t really exist economically. What we did in Ireland was move up a caste, with our American money. […] All for now.

Jim

ROBERT LOWELL

509 First Avenue South

St Cloud, Minnesota

February 11, 1957

Dear Cal,

Your letter came this morning, and while it’s fresh, the news about Harriet, let us congratulate you, Elizabeth as well as Cal, and hope you bear up under parenthood. I’m afraid it gets harder, or has for us, anyway. […]

Your reference to Miss E. drew blood here. Betty hired a woman last fall, and she is still, more or less, with us. But she doesn’t do anything well and, though a character, not enough of one to be useful as such to us. Betty says she (B.) is a coward, or she’d go out and fire the woman. Betty has threatened (over the phone) to mail the woman her apron several times. And so on. My comment on your Miss E.: you couldn’t find a woman like that in a town like this. That’s the last word on that, for the moment. My head feels like a vacant lot where children go to break bottles and swing dead cats. […]

We are sending Harriet (not that she cares) a blanket and trust it will not be found wanting in some particular that Miss E. demands of a blanket. We have used them in our household, but more and more I see that we have made a lot of mistakes. It has been my pleasure to look about me and give thanks that I, that we, don’t live like that. Now I find the contrast not so great. Ah, well, perhaps you’ll write a book and tell us how to live though parents.

All for now. Best to you and the girls.

Jim

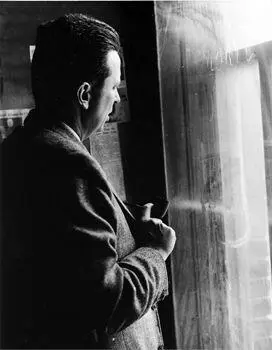

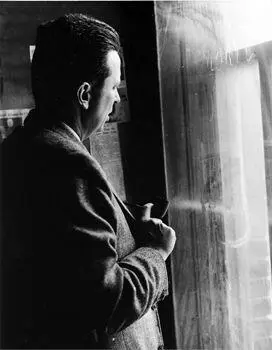

Finding no peace at home for work (or quiet ease), Jim rented an office, suite 7 in the Vossberg Building in downtown St. Cloud. It was decrepit and cheap and he loved it.

HARVEY EGAN

St Cloud

February 27, 1957

Dear Fr Egan,

To you I’m sending my first words written from my office in downtown St Cloud. Your old Royal, fresh from the repair shop, is here. A chair, which may or may not be a bargain at $4 from the Goodwill, is here. A table, cast out by us when we moved to First Avenue South, is here. And I am here. This morning I put a lock on the door, which had none. The jakes is next door, but I haven’t been there yet. There is another room like this next door on the other side, but it is padlocked. Down the hall, toward St Germain, are two lawyers and the Girl Scouts of America, and overlooking the street the realtor and insurance man’s office: he is letting me have this room for $16 a month because of his wife, he said, an admirer of my work. Below me is Walgreen’s; across Eighth Avenue — my window looks down upon it — is Cy Brick’s bar. Up the street is the cathedral. Down the street is the courthouse. Across St Germain is the post office. As you can tell by now, I am in the heart of things — the dead center, you might say.

The room itself reminds me of Quincy College Academy: brown railroad paint on the door and mopboards; a silver radiator; one window arched at the top; and light green walls, cracked and peeling and stained. There are two mops and three rolls of toilet paper and some steel wool in one corner, but I have permission to move these things out. In short, I am all set — either to write during the day, something which is impossible at home, or to go into the rubber-goods business. This is the kind of building the Clementines used to have their offices in in Chicago. I decided yesterday, sitting here wishing the door had a lock on it, that I wouldn’t get pictures or do anything about the walls or floor — which is splintery and worn. Only one object I desire: one of those old-fashioned watercoolers, the kind you put ice in, and a big bottle of spring water, the bottle upside down, and … the bubbles each time you draw one. It’s the bubbles I’d like to have. Otherwise I can stand it the way it is: the peace and quiet of noises which mean nothing to me, traffic, bells, cries of fishmongers and religious-goods butchers from the street.

Читать дальше