Terrestrial nitrogen is almost exclusively 14N, the normal isotope of nitrogen; in the oceans, there is a significant amount of 15N, a heavier isotope that can be distinguished from 14N. Throughout the North American temperate rain forest, salmon swim in thousands of rivers and streams. The five species of salmon need the forest, because when the forest around a salmon-bearing watershed is clear-cut, salmon populations plummet. That's because the fish are temperature sensitive; a small rise in temperature is lethal, so salmon need the shade of the canopy that keeps water temperatures down. In addition, the tree roots cling to the soil to prevent it from washing into the spawning gravels, and the forest community provides food for the baby salmon as they make their way to the ocean. But now we are finding that there is a reciprocal relationship — the forest also needs the salmon.

Along the coast, the salmon go to sea by the billions. Over time, they grow as they incorporate 15N into all their tissues. By the time they return to their natal streams, they are like packages of nitrogen fertilizer marked by 15N. Upon their return to spawn, killer whales and seals intercept them in the estuaries, and eagles, bears, and wolves, along with dozens of other species, feed on salmon eggs and on live and dead salmon in the rivers. Birds and mammals load up on 15N and, as they move through the forest, defecate nitrogen-rich feces throughout the ecosystem.

Bears are one of the major vectors of nitrogen. During the salmon runs, they congregate at the rivers to fish, but once a bear has seized a fish, it leaves the river to feed alone. A bear will move up to 150 yards away from the river before settling down to consume the best parts — brain, belly, eggs — then return to the river for another. Reimchen has shown through painstaking observation that in a season, a single bear may take from six hundred to seven hundred salmon. After a bear abandons a partially eaten salmon, ravens, salamanders, beetles, and other creatures consume the remnants. Flies lay eggs on the carcass, and within days, the flesh of the fish becomes a writhing mass of maggots, which polish off the meat and drop to the forest floor to pupate over winter. In the spring, trillions of adult flies loaded with 15N emerge from the leaf litter just as birds from South America come through on their way to the nesting grounds in the Arctic.

Reimchen calculates that the salmon provide the largest pulse of nitrogen fertilizer the forest gets all year, and he has demonstrated that there is a direct correlation between the width of an annual growth ring in a tree and the amount of 15N contained within it. Government records of salmon runs over the past fifty years show that large rings occur in years of big salmon runs. When salmon die and sink to the bottom of the river, they are soon coated with a thick, furry layer of fungi and bacteria consuming the flesh of the fish. In turn, the 15N-laden microorganisms are consumed by copepods, insects, and other invertebrates, which fill the water and feed the salmon fry when they emerge from the gravel.

In dying, the adult fish prepare a feast on which their young may dine on their way to the ocean. Thus, the ocean, forest, northern hemisphere and southern hemisphere form a single integrated part of nature held together by the salmon. For thousands of years, human beings were able to live on this productivity and achieve the highest population density of any non-agrarian society, as well as rich, diverse cultures.

When Europeans occupied these lands, they viewed the vast populations of salmon as an opportunity to exploit for economic ends. Today in Canada the responsibility for the salmon is assigned to the Department of Fisheries and Oceans for the commercial fishers, to the Department of Indian and Northern Affairs for the First Nations food fishery, and to provincial ministers of tourism for the sport fishers. There are enormous conflicts between the ministries, even though they are responsible for the same “resource,” because their respective constituencies have very different needs. The whales, eagles, bears, and wolves come under the jurisdiction of the minister of the environment, and trees are overseen by the minister of forests. The mountains and rocks are the responsibility of the minister of mining, and the rivers may be administered by the minister of energy (for hydroelectric power) or the minister of agriculture (for irrigation). In subdividing the ecosystem in this way, according to human needs and perspectives, we lose sight of the interconnectedness of the ocean, forest, and hemispheres, thereby ensuring we will never be able to manage the “resources” sustainably.

SEVENTEEN

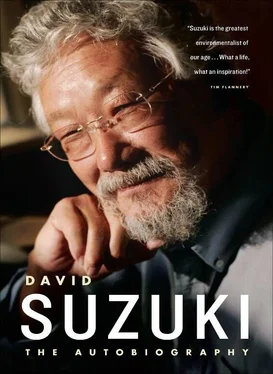

ACULTURE OF CELEBRITY

IT IS ASTONISHING and frightening to see the extent to which the phenomenon of celebrity has come to dominate our consciousness. Not only tabloids and magazines like People and Us Weekly but also the mainstream media seem obsessed with celebrities — and not just for days or weeks but for months and years. When the media lavish as much attention (or even more) on celebrities as they do on weightier issues, how can people distinguish what is important from what is not? The result of our preoccupation with celebrity is that the opinion of someone who might be a lightweight or a fool carries as much heft as the words of a scientist, doctor, or other expert.

Consider how information is packaged in a newspaper: entire sections are devoted to celebrity (entertainment), sports, business, and politics, yet few newspapers assign reporters to write specifically about science or the environment. Our focus on economics often results in big headlines for a developer, promoter, or hustler, while the environmental or social implications of industry are ignored. But when more than half of all living Nobel Prize — winning scientists sign a document of warning — as they did in November 1992, when the Union of Concerned Scientists declared that human activities were on a collision course with the natural world and, unchecked, could result in catastrophe in as little as ten years — they are virtually ignored.

Their predictions have been corroborated by reports about threats to significant portions of mammalian and bird species, the melting ice sheets and permafrost of circumpolar nations, and coral bleaching due to warming oceans. In 2001, I accepted a position on the board of the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, a United Nations — appointed committee created to assess the state of global ecosystems and the services they perform (exchanging carbon dioxide for oxygen in the air, pollinating flowering plants, fixing nitrogen in the soil, filtering water, and so on). The reports from this $24-million project, which involved some 1,300 scientists from more than seventy countries, painted a devastating picture of the natural world on which we are all ultimately dependent.

The final report was released in March 2005 and in Canada was covered in an article on page 3 of the Globe and Mail newspaper. The next day, Pope John Paul II was taken to hospital, and his illness, death, and succession pushed our report out of the news. So a major study warning that Earth's ecosystems are being degraded at an unsustainable rate was a one-day, inside-page wonder.

We live in a time when the military, industry, and medicine are all applying scientific insights, with profound social, economic, and political consequences. As a result, ignoring scientific matters is very dangerous. It's not that I believe science will ultimately provide solutions to major problems we face; I think solutions to environmental issues are much more likely to result from political, social, and economic decisions than from scientific ones. But scientists can deliver the best descriptions of the state of climate, species, pollution, deforestation, and so on, and these should inform our political and economic actions. If we don't base our long-term actions on the best scientific knowledge, then I believe we are in great danger of succumbing to the exigencies of politics and economics.

Читать дальше

![David Jagusson - Devot & Anal [Hardcore BDSM]](/books/485905/david-jagusson-devot-anal-hardcore-bdsm-thumb.webp)