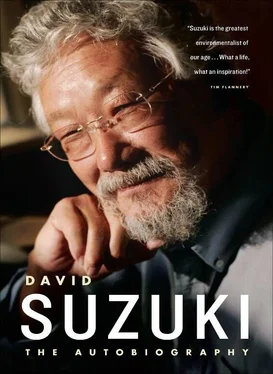

For me, the important thing was not in all of the picky details but in an overarching vision that would establish the real bottom line: that we are biological beings, completely dependent for our good health and very survival on the health of the biosphere. At the David Suzuki Foundation, we felt one contribution we could make at Rio would be such a statement or vision, so I began to draft a declaration that would express an understanding of our place in the natural world. As I began to work on it with Tara, she suggested it should be like the American Declaration of Independence, a powerful document that would touch people's hearts. “How about calling it the Declaration of Interdependence?” she suggested, and it was instantly obvious that was what we were drafting.

Tara and I went back and forth with our efforts and then recruited Raffi, our Haida friend Guujaaw, and the Canadian ethnobotanist Wade Davis, to contribute. At one point I kept writing the cumbersome sentence, “We are made up of the air we breathe, we are inflated by water and created by earth through the food we consume.” That was what I wanted to express, but I wanted to do it in a way that was simple and inspiring. As I struggled with the lines, I suddenly cut through it all and wrote, “We are the earth.”

That was the first time I really understood the depth of what I had learned from Guujaaw and other aboriginal people. I knew we incorporate air, water, and earth into our bodies, but simply declaring that's what we are cut through all the boundaries. Now I understood that there is no line or border that separates us from the rest of the world.

There is no boundary — we are the earth and are created by the four sacred elements — earth, air, fire, and water. It follows that whatever we do to the planet Earth, we do directly to ourselves. I had been framing the “environmental” problem improperly — I thought we had to modify our interaction with our surroundings, regulating how much and what we remove from the environment and how much and what waste and toxic material we put back into it. Now I knew that wasn't the right perspective, because if we viewed ourselves as separate from our surroundings, we could always find ways to rationalize our activity (“too expensive to change,” “it's only a minuscule amount,” “that's the way we've always done it,” “it interferes with our competitiveness,” et cetera). But if we are the air, the water, the soil, the sunlight, then how can we rationalize using ourselves as toxic dumps?

This is what our final document was:

Declaration Of Interdependence

THIS WE KNOW

We are the earth, through the plants and animals that nourish us.

We are the rains and the oceans that flow through our veins.

We are the breath of the forests of the land and the plants of the sea.

We are human animals, related to all other life as descendants of the firstborn cell.

We share with these kin a common history, written in our genes.

We share a common present, filled with uncertainty.

And we share a common future as yet untold.

We humans are but one of thirty million species weaving the thin layer of life enveloping the world.

The stability of communities of living things depends upon this diversity.

Linked in that web, we are interconnected — using, cleansing, sharing and replenishing the fundamental elements of life.

Our home, planet Earth, is finite; all life shares its resources and the energy from the Sun, and therefore has limits to growth.

For the first time, we have touched those limits.

When we compromise the air, the water, the soil and the variety of life, we steal from the endless future to serve the fleeting present.

THIS WE BELIEVE

Humans have become so numerous and our tools so powerful that we have driven fellow creatures to extinction, dammed the great rivers, torn down ancient forests, poisoned the earth, rain and wind, and ripped holes in the sky.

Our science has brought pain as well as joy; our comfort is paid for by the suffering of millions.

We are learning from our mistakes, we are mourning our vanished kin, and we now build a new politics of hope.

We respect and uphold the absolute need for clean air, water and soil.

We see that economic activities that benefit the few while shrinking the inheritance of many are wrong.

And since environmental degradation erodes biological capital forever, full ecological and social cost must enter all equations of development.

We are one brief generation in the long march of time; the future is not ours to erase.

So where knowledge is limited, we will remember all those who will walk after us, and err on the side of caution.

THIS WE RESOLVE

All this that we know and believe must now become the foundation of the way we live.

At this Turning Point in our relationship with Earth, we work for an evolution from dominance to partnership, from fragmentation to connection, from insecurity to interdependence.

I believe the final Declaration of Interdependence is a powerful, moving document that sets forth the principles that should underlie all of our activities. We had the declaration translated into a number of languages including French, Chinese, Japanese, Russian, German, and Spanish, and took copies to give away in Rio, one of the first tangible products of the David Suzuki Foundation.

As we were doing this and setting up the foundation office, Tara was organizing ECO's involvement in Rio and the logistics of hotel, food, travel, shots, and so on. As the time to leave approached, I was increasingly anxious and worried, but the girls saw the trip as an adventure and opportunity. They were so innocent. Despite my concerns, we took off in a state of excitement and hope. I had to fly to Europe at the end of the conference, but Tara had arranged for the children to have a post-Rio reward of a visit to the Amazon.

We landed in Rio, and, as I had feared, it was hot and the air was heavy with pollution from the traffic. I still tended to worry about details — where would we stay, what about food, how would we get around, what about toilets — but Tara is the one who makes those arrangements. My children just ignore me—“Oh, Dad, stop being so anal” is the way they put it. Tara had arranged for an apartment overlooking the fabled Copacabana Beach, but we had too much to do to enjoy the resort.

Tens of thousands of people arrived in Rio de Janeiro to attend the Earth Summit, which included the official un conference, housed at Rio Centro and ringed by armed guards demanding passes to enter; the Global Forum, for hundreds of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) from all over the world; and the Earth Parliament, for indigenous peoples. Each conference was many miles away from the others. I don't doubt that this was a deliberate decision to keep the NGOs and indigenous people as far away from the official delegates as possible, if for no other reason than to minimize the contrast between well-heeled representatives staying at fancy hotels and the rabble like us on minimal budgets staying in the cheap parts of town.

With such distances between summit events, the media had to make decisions about what to cover, and usually Rio Centro was where they hung out because telephones, fax machines, and computers were set up there. As it was, the fun and excitement were to be found among the NGOs, whereas the delegates in business attire were trapped in long, serious, and deadly boring deliberations behind closed doors, completing the final wording of documents to be signed later, when the world leaders arrived.

It was a circus. I hated it. The city was uncomfortable and overrun with cars, and everywhere we went, there were crowds of people trying to be seen or heard. If you're not anal like me, Rio is a wonderful place to visit. The beaches are lovely (although the water is polluted and best left alone), the sun always shines (although it has to make its way through the haze) and there are nightclubs and restaurants galore. We went to churrascarias, amazing places where meat is brought out on skewers and one can fill up on enormous servings of food while children outside beg for leftovers. As in all big cities, but especially those in developing countries, the contrast between the world that tourists inhabit and the extreme poverty in slums is difficult to accept. To prepare for the conference, Brazilian authorities had forcibly removed street people from downtown Rio so that the official delegates wouldn't have to confront the contrasts.

Читать дальше

![David Jagusson - Devot & Anal [Hardcore BDSM]](/books/485905/david-jagusson-devot-anal-hardcore-bdsm-thumb.webp)