Taking the cue from our work on fisheries, we first asked the question, what is the economic position of forestry in the province today? Even though the number of jobs and relative contribution of tax revenues from forestry were steadily declining, the media continued to widely report that forestry contributed fifty cents of every tax dollar in British Columbia's coffers. Dr. Richard Schwindt and Dr. Terry Heaps, economists at Simon Fraser University, agreed to do an analysis of the forest industry, and we published it in 1996 as “Chopping Up the Money Tree.” They showed that the province's economy had become much more diverse than it was fifty years earlier, and that British Columbia's revenues from forestry were about five cents of every tax dollar.

The rant that environmentalists damage the economy and threaten jobs did not reflect reality. Forestry jobs were being lost, but the volume of wood cut was steadily increasing. The province's chief forester was well aware that logging practices greatly exceeded the renewable level. Huge machines were replacing men and working tirelessly and with deadly efficiency, aided by computers. Worse, despite legislation to prevent the export of raw logs, more and more were being shipped to other countries where high-quality jobs were created to process that wood. Every raw log exported cost B.C. jobs and economic potential. The DSF did an analysis showing that Washington State created two and a half times more employment per tree than did B.C., and California five times more.

It bothered me that Canadians, who have some of the best wood in the world, purchase finished products from Scandinavia. I don't believe we are so backward that we can't develop our own lines of wood products, using our own materials. We should use our precious raw logs far more conservatively and ensure that every tree cut creates a maximum number of jobs.

Jim Fulton recruited the dean of arts at UBC, the distinguished scholar Pat Marchak, to perform an exhaustive analysis of forestry in British Columbia. She ended up writing a book in 1999 with Scott Aycock and Deborah Herbert, Falldown: Forest Policy in British Columbia , widely considered the authoritative document on the subject. Pat concluded that a reduction in the volume of wood cut was needed because the current levels were not sustainable. She recommended that the use of wood be diversified to generate more jobs per cubic yard.

Could an ecoforestry code be established that might allow logging while maintaining the integrity of the forest? In 1990, DSF staff member Ronnie Drever wrote a report published as “A Cut Above,” which outlined nine basic principles of what has since come to be called ecosystem-based management (EBM). Although parks and other protected areas, if sufficiently large and interconnected, can help somewhat to protect the biodiversity that sustains our economies, the future is bleak unless land outside parks is developed carefully and sustainably through EBM.

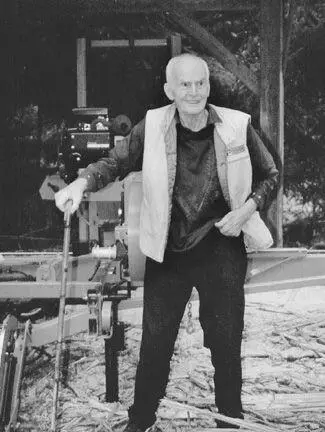

Even before “A Cut Above,” we knew it was possible to log extensively in a sustainable fashion. Vancouver Island forester Merv Wilkinson has logged his forest selectively since the 1950s and removed the equivalent of his entire forest, yet has more board feet of timber growing now than before he began. In Oregon, the family-owned company Collins Pines has been in forestry for 150 years and today does some US$250 million in annual business, yet its forests are considered among the most pristine in the state. Thousands of employees earn a living from those forests, and the company remains globally competitive though all logging is carried out selectively, not through clear-cutting.

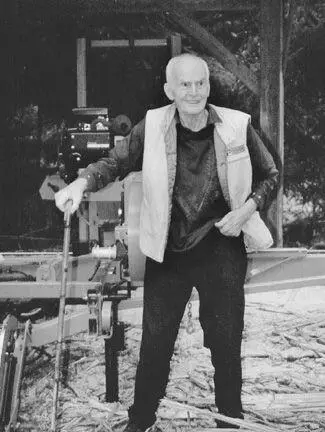

Canadian icon and hero Merv Wilkinson demonstrating

sustainable forestry at his Wildwood farm

But forest companies whose shares are publicly traded on the stock market are driven by the need to maximize return for their investors. There is little incentive to practice sustainable forestry when to do so would mean restricting the volume of trees cut annually to perhaps 2 to 3 percent — nature's annual increase in size. Clear-cutting an entire forest and putting the money in investments would generate double or triple the interest; investing the cash in forestry in Borneo or Papua New Guinea could make perhaps ten times the return. Or the money could be put into something else, like fish, and when they're gone, into biotechnology or computers. Money can grow faster than real trees.

One result of the pressure on forestry companies to reduce their cuts is that increasingly they “high-grade,” logging the most valuable species and ignoring the rest. It's a worldwide problem. In the Amazon, mahogany has been high-graded throughout much of the vast forest. Today in British Columbia, it's clear that companies are high-grading cedar at an unsustainable rate. Cedar occupies such a central place in coastal First Nations culture that the DSF commissioned two studies, “Sacred Cedar” in 1998 and “A Vanishing Heritage” in 2004, that showed how little cedar is being left for traditional use in totem poles, canoes, masks, and longhouses.

We also published a report on culturally modified trees (CMTS), which are trees that have been used by First Nations cultures on the B.C. coast over the millennia. Partially carved canoes emerging out of logs can be found decaying on the ground, and cedar trees still stand that reveal long scars where bark was stripped for clothing; some show vertical house planks have been removed without killing the tree. CMTS are precious artifacts that testify to First Nations occupation and use of the land long before the arrival of Europeans.

In addition to the report, called “The Cultural and Archaeological Significance of Culturally Modified Trees,” we initiated an archaeological training program that enrolled dozens of representatives from eleven coastal villages to become CMT technicians. This generated jobs for First Nations communities, as forestry companies, required to inventory and protect these artifacts, hired such trained personnel to identify CMTS within their logging domain on government land.

WE WANTED THE FINDINGS from our reports to reach a wider audience, and in 1994 the foundation met with Greystone Books, a division of Douglas & McIntyre, the highly respected B.C. publisher. The DSF and Greystone would copublish books meant for a wide audience, and although profit was not the foundation's primary goal, we hoped the books would find an audience big enough to make them relatively self-sufficient. By 2005 we had published twenty books on a wide range of issues. It's been a lot of work, but it has been very satisfying to me to have authored or coauthored ten of them.

As the foundation grew, it seemed to me we needed a different kind of book, a philosophical treatise that would define the perspective, assumptions, and values that underlie our activities. As I began to write it, it forced me to consider matters more deeply. The Sacred Balance: Rediscovering Our Place in Nature brought the fundamental issues into sharp focus for me. To my surprise and delight, the book became a number 1 best-seller in Canada and Australia and continues to sell. As with other books, I signed over my royalties, so that book alone has brought the foundation close to can$200,000 to date.

THE CORNERSTONE OF THE foundation is its relationship with First Nations peoples and communities, and that has remained strong through the years. We understood that the First Nations along the coast of what is now British Columbia have occupied the land for millennia, and that the traditions that had evolved in their relationship with the land would tend to make them better stewards than governments and companies. We also knew that since treaties had never been signed, coastal First Nations should have sovereignty over their land.

Читать дальше

![David Jagusson - Devot & Anal [Hardcore BDSM]](/books/485905/david-jagusson-devot-anal-hardcore-bdsm-thumb.webp)