The day I left Aucre, I was wakened by a horrendous racket, which I learned was the pharmacist spraying insecticide around the village — malaria had come to this part of the forest. It seems there is no way to escape the forces of change, even in the deepest part of the Amazon.

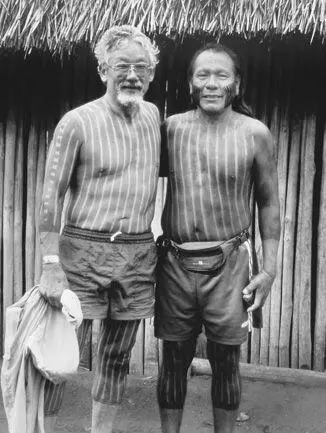

Paiakan and me displaying his wife Irekran's paint job

WHEN I WAS A BOY, another magical place I dreamed of visiting was Australia, home of the fabled duck-billed platypus. The platypus was the sort of creature that fired the imagination of an animal nerd like me, and I yearned to see a live one. With a flat, wide bill like a duck's tacked on to a furry body, webbed feet for swimming, and a poisonous spur on the male's hind legs, the platypus is an egg-laying mammal that suckles its young on modified sweat glands that drip milk onto hairs from which the young can lap it up. In North America, zoos might boast kangaroos or even a koala, but never a platypus.

In the 1960s, when I was starting out at the University of British Columbia, I met Jim Peacock, a brilliant young Australian doing groundbreaking work on chromosome replication in plants. He held a postdoctoral fellowship at the University of Oregon, and we would meet at conferences. We became friends. Unknown to me, he put my name forward for a position at the University of Sydney. Out of the blue, I received a request to apply for a genetics position. I was flattered to receive an unsolicited inquiry right at the beginning of my career, so I sent my very short curriculum vitae, hoping that at least I might be invited to visit and give a talk.

Instead, I was offered the position. I knew the university was the home of an eminent chromosome expert, Spencer Smith-White, which made the institution an attractive place to be. But my marriage was breaking up, and I could not imagine being so far away from my children, so I turned down the opportunity without even mentioning it to the head of my department to try to chisel a raise. I have often wondered what might have happened had I accepted that job.

In 1988, I finally went to Australia, and I immediately fell in love with it. The environmental movement was at a peak of energy and public support around the world, and Australia had recently established the Commission for the Future, a government-funded organization to look at the role of science in Australian society and its place in the country's future. It was a good idea, similar to the Science Council of Canada, which Brian Mulroney dismantled in 1993 during his second term as prime minister.

Phil Noyce (not the Aussie filmmaker of the same name) had been a science teacher who was recruited to the Commission for the Future because of his interest in communicating science to the public. He was young and keen and had encouraged the organization to invite me to give a series of talks in 1988. He would later become a close friend who convinced me of the importance of acting immediately to fight climate change. I had known humanity was affecting Earth's climate, but I felt it was a problem far in the future and that there were other, more pressing issues. Phil disagreed, and the evidence has piled up to show how prescient he was in believing action was urgent. (Tragically, he had an undetected congenital heart defect and died in the prime of his life, while playing tennis.)

I was delighted to receive the invitation and accepted. At last I would be going to Australia. What would I see? Because of the horrific discrimination endured by the Aboriginal people of Australia and the government's infamous “white Australia” policy of restricting immigration to maintain a Caucasian-dominated nation, I expected to have to search hard to see a person of color. In addition, the sexism of the country was well known, and perhaps that is why one of the most globally influential feminists of the time was an Australian, Germaine Greer. I was fully prepared to encounter bigotry, sexism, and anti-gay attitudes. I also thought there would be kangaroos and other marsupials jumping through fields and streets.

How ignorant I was. Like Americans arriving in Toronto to find a huge, modern city devoid of the expected igloos, I landed in Melbourne to discover a huge, sophisticated city of great diversity. I certainly did not expect to find vigorous Chinatowns in Melbourne and Sydney, as well as lots of Thai, Vietnamese, and Japanese restaurants. To my surprise, I discovered sophisticated, multicultural cities with plenty of ethnic diversity. There were no kangaroos in the cities, of course, but I did see them in the wild, where I learned they also gather in farmers' fields and graze openly. In the cities and in “the outback”—less inhabited, vast inland areas — there was an amazing profusion of birds in all shapes and colors — cockatoos, budgies, parrots. Even the “pest” birds like magpies are beautiful. And I'm not a great birder.

On one of my early visits to Australia, Phil took me to Phillip Island south of Melbourne, where fairy or little blue penguins (Eudyptula minor) still live in tunnels in the banks above the beach, and it is possible to listen to them making their gurgling songs in their nests. We can watch as they waddle down to the water's edge in the morning, hesitate, and then collectively plunge into the surf on their way to sea. In the evening they make their way back to their homes, walking past tourists without paying any attention. It's an impressive sight that reminded me of the way animals on the Galapagos Islands failed to recognize us as deadly predators and simply ignored us.

We had a similar experience in 2003 on Kangaroo Island off the southern coast of Australia. There we encountered an echidna; it and the platypus are the only members of that select order of egg-laying mammals, the monotremes. With a sharper beak, the echidna carries a layer of thick, protective quills and makes a living by rooting about for grubs. When we spotted one, we jumped out of our vehicle; the creature ignored us as it dug into the side of the road and we chalked up another amazing encounter.

I asked Phil if I could finally see a platypus, and I was rewarded at the zoo in Melbourne. I was taken behind the exhibits and shown an elaborate waterway constructed for the animals. I was able to watch them for as long as I wanted and saw them being fed their favorite food, a kind of crayfish called a yabbie. It was the realization of my childhood dream and one of the great thrills of my life.

The Commission for the Future was determined to get its pound of flesh out of me, so Phil had arranged a heavy schedule of publicity events in addition to several formal speeches. It was virgin territory for me and for my audience. No one there had heard of me or my ideas, so I could spout off about all of my favorite subjects and be as opinionated as I wanted. It was very gratifying that people were tremendously receptive to my words. It makes sense — Australia is a country whose climate and unique ecosystems encourage being in the outdoors, whether swimming, camping, or just firing up the barbie and chugging a few frosties from the Esky (translation: lighting the barbecue and drinking a few beers from the cooler). Water is a very real issue to everyone. I also suspect Australians were intrigued to hear a “Japanese” (me) who would slang the Japanese for their depredation of global resources like trees and fish. Whatever the reasons, there was a flurry of media interest in me wherever Phil had arranged interviews and news conferences.

The Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) is as important to Australians as the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) is to Canadians, but unlike Canadians, Australians fiercely support and defend the public broadcaster. After relatively small cuts were made to ABC's budget in the late 1990s, more than ten thousand people gathered at a demonstration in Sydney to protest the loss of funding. In contrast, when the federal government made draconian cuts in the CBC's budget, only a couple of hundred people gathered in Toronto to support the corporation.

Читать дальше

![David Jagusson - Devot & Anal [Hardcore BDSM]](/books/485905/david-jagusson-devot-anal-hardcore-bdsm-thumb.webp)