For years, Brazil's urban poor had been promised opportunities in the Amazon under the slogan “Land without people, for people without land.” They had flooded into remote villages in the rain forest, cutting trees to make into charcoal as fuel for factories and to clear land to cultivate crops, which grew for only a year or two in the meager soil. Then the peasants were forced to leave their plots and move on, taking their poverty and malaria with them, as they continued the cycle of burn and cut to plant crops for another year or two.

When I caught up with the crew in Rondônia, they had not been able to take aerial shots because smoke from the burning forest was so thick it was too hazardous for airplanes to take off. I was excited to be there, depressing as the scene was, but the team was demoralized by what they had filmed — poverty, malnutrition, malaria, and children so painfully thin the crew ended up giving them money for medicine and food.

The red soil that had so recently been cloaked with an ancient forest was now exposed in fields that barely supported a pitiful crop of vegetables inadequate for the needs of the large families. Immense trees were cut down without a thought for their ecological role or the organisms they supported (Harvard's E.O. Wilson records that he found more genera of ants on a single tree in the Amazon than are found in the entire United Kingdom).

One of the most destructive activities in the Amazon is the cutting of huge trees to be burned anoxically in sealed ovens to produce charcoal. We filmed dozens of domes in which the wood smoldered to be rendered into lightweight, high-energy fuel, which was then piled in sacks. Magnificent trees were reduced to skeletal pieces of charcoal in pile after pile. I found this devastating. I knew I was witnessing an ecological holocaust, a crime against future generations who would never know the full wonder of this magnificent ecosystem.

We filmed endless scenes of burning — trees, fields, whole forests going up in smoke. At one point we were searching a burn and drove down a narrow road, which suddenly ended in a pond. Rudi Kovanic and the crew lugged their gear around the pond to film the fire on the other side. Since I had plenty of time before I had to appear on-camera, I pulled out my fishing rod and cast toward some logs in the water. On shoots like this, where we were filming scenics rather than interviews with scientists, I might do only one or two stand-ups in a day, so I had a lot of time to stand around and watch. That's why, when we encountered water, I often would pull out my rod and reel and see what might be caught. This time, surrounded by the desolation of burning, I did not expect to catch anything, but at least I had something to do.

I felt a strike on my first cast and watched a beautiful tucunare, a peacock bass that is green and has a characteristic spot on its tail, hit the lure and leap into the air. Tucunare are aggressive predators and attack a lure violently, then fight like mad. They are also one of the most exquisite-tasting freshwater fish I've eaten. When the crew got back to the car, I could promise them a wonderful meal of fresh fish. But I was sure there would be no tucunare left a year or two later, even if there was still water, because the forest cover and the water cycle were being so disrupted by the destruction going on. It was with mixed feelings that I fed the crew — I love fishing and eating fresh fish, but here I was part of a “terminal fishery.”

A crew member who liked to fish was Terry Zazulak, the camera assistant. One night, when we were ensconced in a shack for the night near the Amazon River, we decided to hike to the river and try fishing. It gets dark suddenly and early—6:00 PM — near the equator, and we soon found ourselves squinting in the fading light. The river was flowing very fast, and our gear was too light to sink far enough below the surface to attract a fish. I couldn't see where my lure landed and the river was too noisy to hear it plunk into the water. I began retrieving my lure, then realized the line wasn't coming up out of the water toward me but seemed to be floating in the air. I reeled in faster, wondering whether I had snagged a branch, and felt a klunk. Reaching to the tip of the rod, I felt something furry. It was a bat! It must have swooped in on my lure and been hooked. As a young man, in 1957, I had caught a bat in the same way while fishing in the evening on a canoe trip in Algonquin Provincial Park in Ontario.

I thought back to the enchanting books Animal Treasure and Caribbean Treasure by Ivan Terence Sanderson, then curator of the St. Louis Zoo, about collecting specimens in exotic places, and the daydreams I had had of emulating those field trips when I grew up. According to Sanderson, the people on those expeditions would fire bb pellets into the air, and bats would nail the pellets in flight, knocking themselves out. Sanderson could simply pick them up to add to their collection. Here I had done the same thing with a fishing lure.

Over my decades in television, I've learned that filming in another country can be a huge hassle. No one wants to welcome into their community, or country, a crew that intends to portray them in a bad way. People want to know the purpose of the film, what we intend to show, who we will interview, and so on. Often we have to tiptoe our way through government bureaucracy, red tape, demands for baksheesh, and exchange of money in the black market. We usually have to operate in the local language to make arrangements for planes, hotels, cars, porters, and so forth. When the crew comprises host, producer, researcher/writer, cameraperson, camera assistant, soundperson, and lighting person, along with forty heavy bags of luggage (some metal trunks), a tough and savvy local agent is required to organize it all.

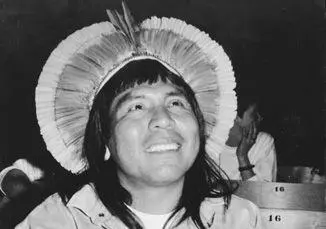

In Brazil, that individual was Juneia Mallus, who was as opinionated and tough as anyone I've ever met. She clashed frequently with members of the crew, but she did a fabulous job. When we said we needed to film an indigenous person who could articulate the importance of the forest and show us through his or her community, Juneia knew who it should be: an extraordinary man she had worked with before — Paiakan, a Kaiapo Indian.

Paiakan

We were to meet Paiakan in the Kaiapo village of Gorotire, which was once reachable only by trails but now had a road from the outside. But “road” is a misnomer. The Amazon is a rain forest, and as we were driving our large truck in, rain converted the road into a slimy red slash through the forest. What was supposed to be an all-day drive turned into an agonizing day and night of grinding our way, slipping and spinning and slumping. John Crawford, our longtime soundman, turned into a heroic figure, driving during the entire ordeal.

I remember clambering out of the back in utter darkness and, scared stiff, creeping on hands and knees along the trunk of a tree, one of two tire tracks across a deep gorge. Somehow John guided that truck on those two thin trunks without slipping into certain death below. Horrific as the road was, it was nevertheless the opening for the influx of “civilized” products — white bread, candy, beer, liquor, tobacco — that pollute the community we were approaching.

Disgusted with what that road had done to this village, Paiakan pulled out and moved far into the forest to establish a new village where his people could continue to live traditionally. After a long search, Paiakan had found the perfect place on a low bluff overlooking a river filled with fish. He called the community Aucre (Ah- oo -cray), apparently named after the sound a certain fish makes when caught. About two hundred people had decided to follow Paiakan and live in Aucre. But he was to meet us in Gorotire.

Читать дальше

![David Jagusson - Devot & Anal [Hardcore BDSM]](/books/485905/david-jagusson-devot-anal-hardcore-bdsm-thumb.webp)