I moved to the University of British Columbia a year after returning to Canada, and in Vancouver I was asked to appear on television to do the occasional book review or commentary on a scientific story. I became more interested in the medium as a way to communicate and ended up proposing a television series to look at cutting-edge science. Knowlton Nash was head of programming at the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) and approved the series to come out of Vancouver. At one point, he called Keith Christie, who had been assigned to produce the series, and asked how “it” was going. Keith asked what he was talking about, and Knowlton replied, “You know, that Suzuki-on-science series.” Keith tells me he said, “That's it,” and the show was called Suzuki on Science . It was broadcast across the country in 1969 and was my first involvement in a television series with a national audience. It ran for two seasons and was renewed for a third, but I quit: we had a lousy time slot and low budget and I saw no future for the show, exciting though making the series had been.

In 1974, Jim Murray, longtime executive producer of The Nature of Things on CBC Television, began a new show called Science Magazine , a weekly half-hour collection of reports on science, technology, and medicine. He had known about my Vancouver-based series, and after we met and talked, he hired me to be the host of the new one. It was an immediate hit, drawing an audience that was 50 percent larger than the long-running popular series The Nature of Things , which had begun in 1960. I took a leave from UBC to host the program.

Halfway through that first season, Knowlton Nash informed us the series would be dropped. We were shocked, but we carried on. At the end of the last show, I told the audience this was the final segment, thanked them for watching, and said goodbye. I didn't lament our passing or plead for support, but viewers responded with letters and phone calls objecting to our cancellation. The series was restored and ran for four more years.

Being interviewed by students in the late 1960s

During the first season of Science Magazine , Diana Filer, executive producer of the CBC Radio series Concern , attended a speech I gave at the University of Toronto. She had proposed a new science series for radio called Quirks and Quarks and hired me to host it when it went to air in 1975. I was host of both Science Magazine on television and Quirks and Quarks on radio, which was a full-time job, until 1979.

Diana also introduced me to Bruno Gerussi, whose CBC Radio show had been a forerunner of Peter Gzowski's This Country in the Morning . Bruno became a good friend, and I would often drop in on him in Gibsons on the Sunshine Coast just north of Vancouver, where he lived while filming his long-running CBC Television series The Beachcombers . On one of those visits, he met my father and grew very fond of him, eventually inviting him to play a guest role on an episode.

Bruno also had a script written in which I played a scientist in search of a rare coastal tree. In one segment of that episode, I appeared with the First Nations actor Chief Dan George, who had starred so powerfully in the film Little Big Man with Dustin Hoffman. I was awed and thrilled to be in his presence, but by then he was quite old and frail. In the story, I seek his advice on where the rare tree might be. When I arrived for the shoot, Chief George was seated in a rocking chair on a house porch and covered with a blanket. As the crew went about setting up the lighting and camera, I tried to chat with him. He replied in a barely audible voice, so I realized I was draining his energy and left him alone; I worried about whether he could perform.

Once the camera was rolling and the producer called out “Action!”, Chief George threw off the blanket, straightened up, and delivered his lines forcefully with that unique voice. As soon as the director shouted “Cut!”, the chief immediately drew the blanket up around his shoulders and slumped back into the chair. He delivered like a trouper by conserving his strength between every take. Now that's being a professional.

In 1979, I left both Science Magazine and Quirks and Quarks to become host of The Nature of Things , which had been reformatted and was to become an hour-long program called The Nature of Things with David Suzuki . I left radio with great reluctance. It was the medium I enjoyed most, because interviews were relaxed, and there was an opportunity to be spontaneous, humorous, and even risqué, since tapes could be edited and still retain warmth and intimacy.

In contrast, television is very controlled, because airtime is so valuable. After I've given a speech, I often encounter people who tell me I'm so different from my persona on TV. But it shouldn't be a surprise; that person on-screen is a creation of the medium. My on-camera appearances are carefully planned and controlled, then prepackaged, and the narration is laid down in a studio, where my reading is carefully delivered to fit the pictures. Because radio burns through material and, as host of Quirks and Quarks , I had to do all of the interviews, it demanded far more of my time than television. There was also no denying the much greater audience size of television and therefore, potentially, its greater impact. So I reluctantly gave up Quirks and Quarks , but I continue to take vicarious pride that it has endured and flourished under a number of excellent hosts.

When I began to work in television in 1962, I never dreamed that it would ultimately occupy most of my life and make me a celebrity in Canada. I thought I might have a knack for translating the arcane jargon of science into the vernacular of the lay public, and I felt that speaking on television was a responsibility I had assumed by accepting government research grants and public support in a university. When I appeared on a television show for the first time, I enjoyed the novelty, but I did not anticipate the notoriety that would come from being on-screen regularly. Looking back, I realize how incredibly naive I was. I just didn't understand the relationship between a viewer, television, and information.

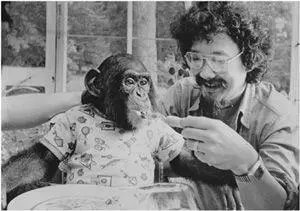

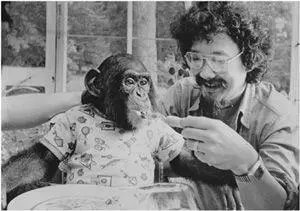

Nim Chimpsky, who was taught to use sign language by Herb Terrace of Columbia University

Television is an ephemeral medium; a program we might work for months to create flashes onto the screen to an audience often distracted by other activities — feeding the kids, answering the phone, going to the toilet, walking the dog, getting a drink. Viewers aren't fully engaged through the entire program, and what is ultimately remembered may be a snippet. And if a show is part of a series such as The Nature of Things with David Suzuki , in which diverse topics are covered, the subject matter of any given show may be forgotten, but the one constant feature from week to week — the host — is remembered.

Over time, a relationship is established wherein the audience comes to trust the host and to believe in what he or she is conveying. Think of the enormous following of people like American journalist Walter Cronkite and Canadian counterpart Peter Mansbridge. In the same vein, I too am transformed from being the carrier of information to an “expert.” People assume I am an authority on each subject we cover on the series and that I must know everything in the area of science, the environment, technology, medicine, and so on. Strangers often approach me to ask a very specific question about treatment for a disease, a new technology for cleaning up the environment, or an obscure species discovered in the Amazon. When I answer that I have no idea, they stare in disbelief and demand, “What do you mean, you don't know? I thought you knew everything!”

Читать дальше

![David Jagusson - Devot & Anal [Hardcore BDSM]](/books/485905/david-jagusson-devot-anal-hardcore-bdsm-thumb.webp)