It’s at age one that we acquire our first words. This story, which made me so melancholy as a girl, is, among other things, about the price we pay for language, for the ability to tell our mothers that it’s not our teeth that are upsetting us but something else. It alludes to what we have given up to be understood by her and all the other adults, our lost brotherhood with the rest of creation. Words are what separate us from the animals, or as Travers would have it, from the elements themselves, from everything that can simply be without the scrim of consciousness intervening.

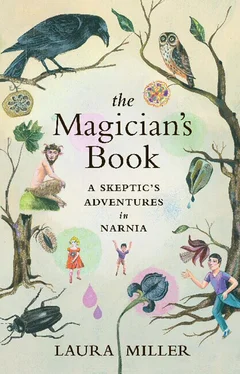

In an early, abandoned version of The Magician’s Nephew, Lewis experimented with a similar theme. He has the story’s boy hero, Digory, able to understand the language of animals and trees until Polly, the little girl who lives next door to him in London, persuades him to cut off a branch from the big oak in his garden. In Lewis’s tale, the separation is literal, physical, and violent, a sin against nature itself. Travers makes the more eloquent choice; to become ourselves, to be human, we must necessarily set ourselves apart.

In Narnia, this mournful rift is healed; there, people can talk to animals, to trees, and sometimes even to rivers (as happens in Prince Caspian ). Human beings have longed to communicate with the universe since time immemorial — a profound, mystical longing. Tolkien described it as one of the two “primordial desires” behind fairy tales (after the desire to “survey the depths of space and time”); we want to “hold communion with other living things.” But since children are literalists and materialists, not mystics, their love for animals, and for stories about people who can talk to animals, is seldom understood as a manifestation of this desire.

To say that, as a child, I — and my brothers and sisters and most of our friends — loved animals would be an understatement; much of the time we wanted to be animals. Take us to a park or some place with a rambling yard, and we’d immediately begin mapping out the territory for one of our elaborate games of make-believe. At first, we pretended to be various woodland fauna, inspired by the Old Mother West Wind books by Thornton Burgess, a series our mother read to us. At home, one of us would clamber up onto the roof of our ranch house (via the top bar of the swing set) to play the eagle who came swooping down to pounce on the squirrels and chipmunks below. Later, after The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe introduced me to classical mythology, we invented a game we called “mythical creatures,” and played at being griffins, unicorns, and winged horses.

This preoccupation with animals starts early. Two friends of mine, toddler twins named Corinne and Desmond, began pointing at themselves and saying “This is a puppy” almost as soon as they learned to talk. As time goes by and the impossibility of such imaginings becomes obvious, the ache for contact with the animal world grows more desperate. By age seven, when I first read The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, I longed for some better rapport with the family cats and the neighborhood dogs, with any kind of beast, really. Animals seemed like relatives left behind in the Old Country, except that the growing expanse that separated us wasn’t a physical ocean but a cognitive one. They stood on the dock, getting ever smaller, while we children watched from the deck, on the way to a new, supposedly better way of being in the world, haunted by the image of what we were losing.

Animals, like infants, belong to the vast nation of those who communicate without words, through gesture, expression, scent, sound, and touch. Children are immigrants from that nation and, like most recent immigrants, still have a mental foothold on the abandoned shore. I believed, probably correctly, that I understood animals better and cared about them more than the adults around me. I could still faintly remember what it was to be like a beast, before language complicated things. But I didn’t appreciate the inverse relationship between the individual self I was building out of the new words I acquired every day and the inarticulate world that moved away from me as my identity gained definition.

Watching Corinne and Desmond grow up, I have noticed another drawback to learning to talk: speaking also ushers in the stage at which grown-ups stop doing anything you want just to make you stop crying. It’s only when you can ask for something with words that people expect you to understand “no.” So age one also marks the beginning of our entry into human society proper, where compromise is the price of admission. Many adults — and especially the authors of great children’s books — view growing up as a kind of tragedy whose casualties include innocence and the capacity for wholehearted make-believe. But kissing Puff the Magic Dragon good-bye happens later, on the brink of prepubescence. Travers, in her chapter on poor John and Barbara Banks, seems to be saying that even the smallest children have already suffered a heartbreaking separation, before they leave their cribs.

When I first read William Wordsworth’s “Ode: Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood,” with its lines about birth as the beginning of an exile from heaven, I thought of John and Barbara:

Our birth is but a sleep and a forgetting:

The Soul that rises with us, our life’s Star,

Hath had elsewhere its setting,

And cometh from afar:

Not in entire forgetfulness,

And not in utter nakedness,

But trailing clouds of glory do we come

From God, who is our home:

Heaven lies about us in our infancy!

Shades of the prison-house begin to close

Upon the growing Boy …

Wordsworth surely didn’t mean to include language among the shades of the “prison-house” that close in upon “the growing Boy”; poetry, after all, was a kind of religion to the Romantics. Yet incarceration was also the metaphor that occurred to the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche when he called words and grammar a “prison-house of language.” Some poststructuralist philosophers would go on to insist that our thought is so shaped by language that the only reality we can ever know is entirely constructed of it. We live in a hall of mirrors, and the mirrors are made of words.

Words, furthermore, introduce us to our most implacable enemy: time. Developmental psychologists believe that memory begins with the learning of language; to speak (or more accurately, to understand speech, since most children can comprehend before they can articulate) is to remember. With memory comes the capacity to dwell on the past and to anticipate the future; without memory, how could we know our lives and our selves? And without knowing these things, how could we own them? But as Travers’s mournful little parable would have it, to speak is also to forget — to forget what it is not to remember, to forget what it feels like to live the way animals do, in a perpetual now, unaware of death and outside of time.

I can’t shake the feeling that even if children don’t cognitively grasp the miraculous tragedy of consciousness, they nevertheless feel the aftershocks of the journey they’ve made. Animals inhabit the world of raw experience we’ve left behind; animals are the people of our lost homeland. To a child, an animal seems like a compatriot. The attachments that I had to the animals I knew were every bit as powerful as my feelings toward, say, my siblings (and less ambivalent, too, since I wasn’t competing with the family cats for my parents’ attention or a bigger share of the french fries). It’s true that some adults still feel this way about their pets, and if you ask them why, the explanation often has to do with the transparency of animals’ affection, their sincerity, which also turns out to be connected to their lack of language. Animals can’t speak, ergo, they can’t lie.

Читать дальше