As the evening goes on, people talk about whether they will come back for the next attempt or not. I will not. This will be my first time leaving Florida with the spacecraft I came to see launch still on the ground.

As I’m getting ready to leave, Omar asks if I’d like to set off a model rocket with him in the morning. He’s bought a scale model of the SpaceX Falcon, and he offers it as a sort of consolation because I didn’t get to see the real one go off.

I answer immediately, “Of course!” We make plans for when to meet up. I have a twelve-hour drive tomorrow and really should be hitting the road as early as possible. But I like the idea of seeing Omar one more time before I go, and besides that, I sense a metaphor.

* * *

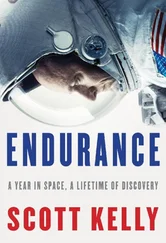

What does it mean that we’ve done so much, and what does it mean that we’ve decided to stop? I talked to Andy about the unlikely chain of events that led to the start of NASA and Project Mercury, and though it goes against some of the patriotic pride we usually take in our space program, I’ve had to accept that the political will to keep spaceflight going just doesn’t exist anymore, hasn’t for a long time. We have been infected by the myth of public support for spaceflight for so long, it’s kept us from properly understanding how we got to where we are. As historian John Logsdon writes, “Apollo was a product of a particular moment in time…. Its most important significance may well be simply that it happened. Humans did travel to and explore another celestial body.” It happened, but we never quite understood why we were doing it. There was never enthusiastic public support for human spaceflight for its own sake. I should probably say this again: There was never enthusiastic public support for human spaceflight for its own sake. At best, there was support for beating the Soviets at a game that they had grabbed a head start on, a game that seemed to have to do with military, not scientific, superiority. People said they didn’t want to go to bed under a Soviet moon, and they were serious. The power of that brief surge of emotion was enough to start Apollo, but the moon project had lost its relevance as a national project by the time it was actually accomplished. The power of that brief interest, combined with the immense fun and pageantry and good feeling brought about by the successes of the heroic era, and its heroes, has been enough to fuel fifty years of NASA. This is remarkable in and of itself, of course. Few projects based on such short-lived support have shown themselves to have such endurance.

But maybe this is a part of the answer to the question I’ve been torturing myself with all this time: Why are we stopping this when everyone seems to like it? The answer is that public support for spending the money, to the extent it ever existed, was long gone by the time I was born. The whole thing depended on a confluence of forces that can’t be re-created. Those of us who love it should count ourselves lucky that it somehow accidentally happened at all, and, I suppose, we should accept the fact that it’s finally run its course.

I discovered at this attempt that it’s simply impossible to stand outside in the middle of the night watching an enormous object on the horizon try to launch itself into space and not root for it. At least, it’s impossible for me. And once you’ve stood out there and rooted for it, you kind of hope for it to succeed even once you’re not watching it in person anymore. A few days later, I will set my alarm for the middle of the night in order to wake up and watch the second attempt to launch Dragon. I will be pleased and confused when it does launch successfully. I find I have started to care about this spacecraft. Not in the same way that I care about the space shuttle or the Saturn V, or even the Redstones and Atlases—nothing would ever come close to that—but when the little white Dragon on my phone’s screen slowly pulls itself up into the sky, the way spaceships do, I will feel a surge of joy for it, clap my hand over my mouth to keep from waking my husband. Then I will have to stop and think about what that means.

What does it mean that we went to space for fifty years and then decided not to anymore? This question is as difficult to grapple with as ever because, I’ve discovered, it’s actually many questions at once. What does it mean to stop exploring? What does it mean to disappoint children? What does it mean to cancel the future? What does it mean to hobble the one government agency that people feel good about? What does it mean to hope for private companies to take over something we used to do as a nation? What does it mean to stop spending the money?

One thing I notice every time I’m at the Cape is how literal all the workers are about their work. I’ve kept calling the work here some kind of dream, yet what I see over and over is that, to the people who do the work, nothing is a dream, a metaphor, a fairy tale: everything is exactly what it is. If the work here results in something beautiful, it is beautiful by accident, as form follows function. It is the reflected beauty of our intentions I’m seeing, not someone’s abstract idea of beauty.

Hugely wasteful, hugely grand? If we wanted to go back to the moon now, we couldn’t do it. We’d have to start over. But here’s the thing I keep coming back to: the goal itself was beautiful, beautiful in its imagery and in its impossibility. It was a dream that even the literal-minded could share—even Neil Armstrong, as a boy, had dreamed a recurring dream that he could hover above the earth by holding his breath. The dream came true, even if it was only a fluke. Even if it was only for a while.

* * *

In the morning, I find Omar at the park, a perfect location with four full-sized soccer fields, all of them unused today. We walk into the center of the four fields, leaving as much empty space as we can around us. Omar carefully unpacks the model’s pieces and starts setting it up, telling me about how it works as he assembles it. But a piece is missing; it must have fallen out in his car. He heads back to the parking lot to find it, a five-minute round trip. To pass the time, I snap a few pictures of the rocket and tweet one along with the words:

w/ @izqomar: Failure is not an option.

Ten seconds later, I look up to see Omar heading back toward me with the missing piece held aloft triumphantly. He’s still far away, but I see him startle, then make an expression exactly as if his phone has just vibrated in his pants. He fishes the phone out of a pocket, looks at it, and smiles. He’s seen what I put on Twitter.

“That’s pretty funny,” he calls out as soon as he’s within earshot. A second later, my phone buzzes. Omar has retweeted me, and now a few of his followers are weighing in—he has over five hundred. Now with all the pieces in hand, Omar kneels down to finish assembling the rocket.

“Now, I’ve made a few mods,” Omar explains from his position on the ground. He shows me where a tube meant to guide the rocket along a metal rod had fallen off the fuselage earlier—Omar had replaced it by supergluing a fast-food straw in its place. This adaptation held together through one previous launch, but today it looks to be coming apart. Soon the straw comes off in Omar’s hand. He grunts in exasperation.

“That’s definitely a scrub,” he announces, disappointed.

“But I’ve already tweeted that failure is not an option,” I point out. I’m only kind of joking.

“Do you have any duct tape in your car, or anything like that?” Omar asks. I don’t, but I start thinking about other ways to attach the straw to the body of the rocket. I come up with the idea of using my hair elastics, and that seems to work. Our jury-rigged rocket is set up on its stand, its white body striped with my brown hair elastics, poised for launch. Omar and I step away as far as the detonator cord will let us. Omar is extremely careful working with the wires and the detonator, and he describes what he’s doing as he does it, probably a safety thing he learned at work. Once everything is set up to his satisfaction, Omar takes a deep breath and says, “Okay. You ready?”

Читать дальше