* * *

American spaceflight did not begin at the Kennedy Space Center; nor did it begin at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station across the Banana River from here. It began in the early twentieth century when three men working independently in three different countries all developed the same ideas more or less simultaneously about how rockets could be used for space travel. Konstantin Tsiolkovsky in Russia, Hermann Oberth in Germany, and Robert Goddard in the United States all came up with an eerily similar concept for using liquid fuel to power rockets for human spaceflight. I’ve seen this pointed out as an odd coincidence, one of those moments when an idea inexplicably emerges in multiple places at once. But when I read through each of these three men’s biographies I discovered why they all had the same idea: all three of them were obsessed with Jules Verne’s 1865 novel De la terre à la lune (From the Earth to the Moon). The novel details the strange adventures of three space explorers who travel to the moon together. What sets Verne’s book apart from other speculative fiction of the time was his careful attention to the physics involved in space travel—his characters take pains to explain to each other exactly how and why each concept would work. All three real-life scientists—the Russian, the German, and the American—were following what they had learned from a French science fiction writer.

Spaceflight began in earnest on October 4, 1957, when the Soviet Union launched the first artificial satellite, Sputnik, into orbit. The degree to which Americans were shaken by Sputnik is all but incomprehensible to people born too late to remember the Cold War. We can only know it from books and films—my favorite is Homer Hickam’s memoir Rocket Boys , in which he describes standing outside on cold October evenings to watch the tiny light of Sputnik go by. We can only imagine their panic when they heard on the radio that steady Soviet beeping. The thing was streaking by like a star over Americans’ cities and towns. And what was to stop it from raining weapons down upon Americans from that vantage point? If Sputnik wasn’t actually big enough to have weapons capabilities, maybe the next satellite would be.

It is fair to say that Sputnik completely changed the way Americans in positions of power thought about both weapons and spaceflight. Up until that fall of 1957, the idea of using the rockets developed for World War II to make science fiction fantasies come true was at best a tough sell. But once everyone heard that ominous beeping, the goal of getting an American satellite up there too suddenly became urgent.

A tiny government agency called the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics had been in charge of overseeing the development of new airplane technology, including the plane that Chuck Yeager had flown to break the sound barrier in 1947, but their ambitious plans for sending pilots into space had always been dismissed as too expensive, too dangerous, and ultimately pointless. After Sputnik, President Eisenhower took a new interest in the activities of NACA and turned it into NASA, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, with an infusion of funding. NASA was meant to beat the Soviets at their own game. The space race was on, and it seemed that the Soviets already might have won it.

Project Mercury began the same day NASA did, folding in a poorly funded Air Force project known as Man in Space Soonest. Everyone knew how far ahead the Soviets were, but it suddenly seemed there was no choice but to try to catch up. Not to do so would be to concede defeat. Entering the race would mean a justification for a huge upsurge in government spending, some for new projects, some for existing but underfunded ones. Public education was one of the first areas to feel the effects—high schools revamped their curricula to include more math and science, as well as Russian-language instruction.

At the end of World War II, the best of Germany’s rocket designers had been recruited to the United States by a covert government group that later became the CIA. The project was called Operation Paperclip because the Germans’ affiliation with the Nazi party and/or the SS had to be covered up through fake documents, which were paperclipped to their files. The most important German rocket expert was Wernher von Braun, who had been responsible for the development of the V-2 rocket used to bomb Allied cities. Now an American citizen, von Braun had been working to develop rockets for the US Army since 1945 and had been finding the support and funding offered him and his staff at Fort Bliss to be insultingly inadequate. But all that changed in 1957 with Sputnik, and the rocket designers soon found themselves working for NASA and enjoying much better accommodations. Suddenly everyone was interested in what von Braun and his team could do and wanted them to have all the money they needed to do it.

As it turned out, the United States came close to being the first to put a human being in space, had it not been for a couple of setbacks and an abundance of caution. As it was, a Soviet cosmonaut, Yuri Gagarin, made the historic first flight into space on April 12, 1961, and Alan Shepard followed soon after, on May 5. Riding the wave of that enthusiasm, and needing a way to recover from the Bay of Pigs debacle in Cuba, President Kennedy made his move.

On May 25, 1961, Kennedy spoke to a joint session of Congress and made an ambitious pitch: “that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the earth.” Not long before, Kennedy had had nothing but skeptical things to say about human spaceflight. The Soviets had changed the script for him. When I watch his speech to Congress now, I am struck first of all by his youth. He was forty-three years old, one of the youngest people in the room, and he appears younger than his years. I’ve always known that in this speech he urges lawmakers to strike out on a bold path, but I never knew until I watched the entire speech myself that he does so with such sincerity and humility. He emphasizes how difficult and expensive the project will be, that there is no guarantee of success. He admits that “I came to this conclusion with some reluctance,” and then closes with this: “You must decide yourselves, as I have decided. And I am confident that whether you finally decide in the way I have decided or not, that your judgment, as my judgment, was reached in the best interest of our country.”

What Congress decided was to embark on what would turn out to be the largest peacetime engineering project ever undertaken by the US government. They felt they had little choice, with the terrifying possibility of Soviet weapons in orbit and on the moon. The role of this fear in influencing space policy is not to be underestimated, and proponents of spaceflight would try to keep this fear alive as long as it had any plausibility. Kennedy’s speech to Congress is a rousing piece of rhetoric and a key moment in spaceflight history, but it also shows us the first instance of a recurring spectacle: an impassioned spaceflight advocate begging a fickle Congress for money. The script would be rewritten again and again for the space shuttle and the International Space Station, and the results would never be as unequivocally favorable again.

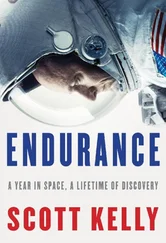

Gus Grissom flew next, in July, repeating Shepard’s suborbital flight, then John Glenn became the first American to orbit the planet, on February 20, 1962. Scott Carpenter and Wally Schirra followed, and Gordon Cooper made the last Mercury flight, becoming the first American to spend over a day in space and the last to travel in space alone. Already the Gemini project was under way, named for the two-man crews who would work through the problems necessary for getting to the moon: creating larger and more reliable rockets, mastering the biomedical challenges of enabling astronauts to survive in space for weeks at a time, developing methods for docking two vehicles together in space, and testing the space suits and other equipment necessary for space walks.

Читать дальше