Sitting at the undersized desk in my Nashville hotel room, I wrote a two-page introduction outlining Buzz Aldrin’s accomplishments. I decided to end with the inscription on the stainless steel plaque that he and Neil left behind on the surface of the moon. I stood up to practice reading the introduction out loud to make sure it was under two minutes, and when I reached the end, I tried to deliver the inscription boldly: “Here men from the planet Earth first set foot on the moon…. We came in peace for all mankind.” But, embarrassingly, I got choked up. Some people are the same way with the preamble to the Declaration of Independence or the last verse of “The Star-Spangled Banner”; for me, this is the poem that most stirs my patriotic sentimentality. It’s still hard to believe that these words rest on the surface of the moon two hundred and fifty thousand miles away, have rested there since before I was born; it’s even harder to believe that the plaque so modestly refrains from bragging. I’ve always thought this was part of the answer to my question about what the era of American spaceflight has meant.

So I wait on Seventh Avenue in downtown Nashville, where I am to meet Buzz. It’s a disconcerting sensation, waiting on a sidewalk with my coat over my arm, dress and lipstick on, like waiting to be picked up for a date. Book festival patrons on their way to events meet my eye, seem to wonder why I’m standing here. I’m waiting for Buzz Aldrin , I want to tell them. But I would sound like a lunatic.

When the limo finally pulls up, Buzz Aldrin pops out of it as if on springs.

“I’m Buzz Aldrin,” he says as I approach him. But I’d know him anywhere. He is nearly eighty years old, but he is still cartoonishly handsome in a Dudley Do-Right way, with the deep chin cleft and sparkling eyes of a forties movie star. To my delight, he wears the same blue blazer he wore in the YouTube punch video; the color brings out the startling blue of his eyes. Buzz Aldrin is animated, twinkling, even, while we shake hands. He has absolutely no trace of the frailty or hesitation one might expect from a man his age. I introduce myself, and he repeats my name back to me, which thrills me.

I realize I am holding on to Buzz’s hand too long. I can’t help it. I am exquisitely aware, in that moment, of the fact that his hand has been on the moon. This hand—this eighty-year-old white man’s hand—has traveled farther than anything I will ever again have the chance to touch. This hand, I think in that split second, may still have residual moon molecules on it. I think to myself: I am touching a moon hand. These thoughts are goofy and vaguely childlike, like so many we have about spaceflight, but I know the day is coming, not too long in the future, when there will no longer be any living human beings who have walked on the moon, no more moon molecules lingering in the creases of aging men’s hands. All this makes a handshake hard to pull off elegantly.

Buzz turns to help his wife, Lois, out of the car. Lois is tiny and elegant, dressed in a sequined NASA shirt. They both carry Louis Vuitton overnight bags, part of his compensation for appearing in the ads connecting the brand with the fortieth anniversary of the moon landings. They have just arrived from a long flight but appear perfectly pressed and alert.

Once we reach the authors’ green room, Buzz and I put on our name tags, look in our author goodie bags (each containing, among other things, a Moon Pie and an airplane-sized bottle of Jack Daniel’s), and settle in to wait for our event. We have nearly two hours until his talk is scheduled to begin. Lois has brought a magazine and leaves Buzz and me to chat. This is my chance.

I don’t really know how to bring up my question, though. I am suddenly conscious of how annoying it must be for Buzz Aldrin to have these big questions sprung at him without warning, knowing that his answers may appear in print. He would probably rather relax and make small talk like anyone else. I hate to be the one to do this to him, to force him into interview mode.

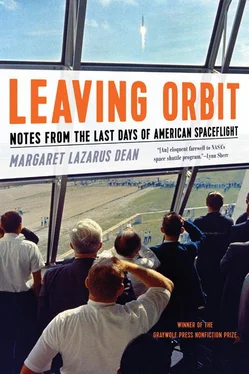

While I dither internally, Buzz asks politely about my book. I hand him a copy (having finished my own book event earlier in the day), then watch as he scans the jacket. Even though my book has been out for a while, has withstood reviews and polite corrections from people like Omar, this still makes me extremely nervous.

“Did you read Encounter with Tiber ?” Buzz asks.

I murmur vaguely. Encounter with Tiber is a 1996 science fiction novel Buzz cowrote with John Barnes. I own the book—it’s a mass-market paperback with a debossed alien solar system on its cover. I’ve read the chapter that describes a fictional space shuttle disaster with great attention. But the novel spans centuries—millennia, actually—and begins with a seventy-five-character dramatis personae, longer than those of most Russian novels. Despite glowing reviews from the likes of Alan Shepard, Michael Collins, and Arthur C. Clarke, I’ve never gotten around to finishing it.

Buzz asks a few polite questions—what kind of research I did, whether I, too, had been a thirteen-year-old when the space shuttle Challenger exploded. I tell him I was.

“A terrible thing,” Buzz says. “We always thought the shuttle project was so much safer. Going to the moon was supposed to be the big risk, and the space shuttle was supposed to be this move toward safety and reliability.”

This was part of the problem, of course—people thought the shuttle was as safe as an airliner, and were bored by that safety; they felt that much more betrayed when it turned out not even to be reliable. Buzz is right that it was a big risk going to the moon—I’d read the night before that President Nixon’s speechwriter, William Safire, had drafted a speech for the president to give in the event the lunar module of Apollo 11 was unable to lift off the moon’s surface. The speech is eloquent and moving, a haunting voice from an alternate universe in which the worst has happened. It begins with the line: “Fate has ordained that the men who went to the moon to explore in peace will stay on the moon to rest in peace.”

“It was a terrible thing that one of the crew was a teacher,” Buzz adds.

I consider telling Buzz about my theory that the inclusion of a schoolteacher on the flight, and the ill-fated attempts to publicize that particular flight to schoolchildren, altered irrevocably my generation’s feelings not only about spaceflight but also about our country, about the way the world works. American spacecraft had been taking astronauts safely to space and back since long before we were born, and so we understood human spaceflight as a normal state of events, a pre-existing condition, a birthright. For those who were already adults, Challenger was a terrible accident, but for children it was something more like a betrayal of our deepest trust. It permanently damaged our faith that the world made sense and that the adults were properly in charge of it.

But I’m not confident this line of thinking will interest or engage Buzz. At a certain level, I’m afraid of seeming guilty of a particular type of unappetizing generational self-pity (“Boo-hoo, we watched a rocket explode on TV”) when everyone knows that, especially compared to his, my generation was strangely immune from tragedy. That an accident resulting in the deaths of seven people was, for us, the worst thing that had ever happened was evidence of how very sheltered we had been.

“I always thought John Denver should have gotten to go on that flight,” Buzz says, interrupting my thoughts.

“John… Denver?” I repeat, wondering whether he really means the singer.

“Yeah, you know, ‘Rocky Mountain High’? He was a great advocate of spaceflight, and when NASA first talked about sending a civilian, they considered sending a creative person, a performer. John Denver could have written a song in space that would inspire generations to come.”

Читать дальше