Standing in the gift shop in front of a wall displaying all the mission patches from every spaceflight, I think about all I’ve seen today, all that will still occur here over the next year. The idea forms in my mind again that I could witness and write about these last launches. Or rather, it might be more accurate to say it’s at this moment the idea solidifies into intent. Because it’s been brewing all day, the idea I keep pushing to the back of my mind, this feeling that I should come back for these launches and write about them. I felt it in the VAB, and I felt it in the Orbiter Processing Facility, where it seemed I could almost reach up to touch the landing gear of Endeavour. I felt it at the Landing Facility with its three miles of runway dotted with alligators who are under the impression that the warm concrete has been laid out for their sunbathing comfort. That night at dinner with Omar and my family, he tells us about the excitement of launch days when he was little, about being awakened by the sonic booms of orbiters punching through the atmosphere in the middle of the night. He tells us about the terrible day his father came home from work after having spent the day in Launch Control searching his data screens for some sign of what had happened to Challenger.

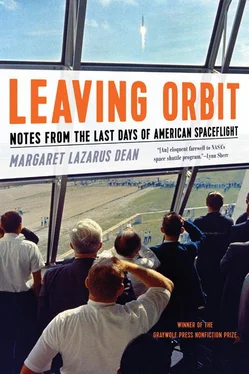

All the books I’ve read about American spaceflight are about a trajectory still on the upswing. Even the books written post- Columbia envision a shuttle program righting itself, restoring our faith, and carrying us over until the next vehicle is ready to launch. No one has yet tried to grapple with the end that is now in sight. Only when something ends can we understand what it has meant.

In the parking lot, my father and Judy shake hands with Omar and thank him for everything he’s done today. While they get into the rental car and set the GPS for the airport, Omar tells me I should come back for the Discovery launch.

“I’d love to,” I say. “But it’ll probably be during a busy time in my semester.”

“Sure,” Omar says nodding. “I understand it’s hard to get away. But remember—it’s the last one.”

I hug him before getting into the backseat of the car with my family. Omar stands in the parking lot waving as we pull away, until he is a tiny dot in the rearview mirror.

I’ve read that the twentieth century might be remembered only for the atomic bomb, the industrialized slaughter of human beings, and the first steps away from our home planet. If this is true, the end of American spaceflight is going to be one of the more significant moments of my lifetime, significant beyond the three missions left and the sixteen astronauts still preparing to go into space. By the end of Family Day, when we are all saying our good-byes, I have come to feel that the end of the space shuttle is going to be the ending of a story, the story of one of the truly great things my country has accomplished, and that I want to be the one to tell it.

* * *

The night I get home from Cape Canaveral, I e-mail Omar to thank him again for inviting me, then go to the NASA website and find the shuttle launch manifest. One more mission for Discovery in the fall and one for Endeavour the following spring. A last mission for Atlantis , if it’s added, will be in the summer. After that there will be no more.

In another window on my computer is a Flickr photo set belonging to a woman I don’t know. The photo set shows the woman visiting the Kennedy Space Center on some sort of special escorted trip. The way her captions are written tells me she doesn’t know nearly as much about shuttle as I do—she uses slightly the wrong terms for everything. Worse, her writing lacks the enthusiasm I feel properly befits her experience. Not only does she not report crying upon entering the Vehicle Assembly Building, she doesn’t even seem to understand it as a special privilege. As the photos continue to scroll by, I get more upset, because here she is donning a full-body cover-up and climbing into the crew cabin of an orbiter, an enormous privilege. The astronauts themselves don’t take this lightly. In the pictures, the woman looks pleased and amused but not mind-blown. It was NASA’s message about the space shuttle from the beginning that it would be cheaper, safer, more routine, than Apollo, more like commercial air travel. Maybe that message sank in too far with some people, and maybe this is part of what has doomed the shuttle. I stare at the woman’s pictures for a while longer, then close the browser window.

“I know my rockets,” I’d assured Omar, but did I? There are always people who know more, have seen more. I’ve seen one launch, which is more than most people can say. But Omar has kept company with the orbiters themselves. He has seen dozens of launches and has spent workdays, workweeks, work years inside the buildings I’ve waited a lifetime to enter. I’ve been inside the VAB now, but this horrible woman has been inside the crew cabin. There will always be someone who has seen more.

I print out the launch manifest and make some notes in the margins. After we get our son to bed, I show the printout to my husband, and though he clearly dreads the chaos this project will cause in our household, he agrees that this story needs to be written. Chris is a writer too, and a freelance editor; each of my absences will seriously cut into his time to work. He will care for our three-year-old son while I go to Florida multiple times and on a maddeningly ever-changing schedule. I will have to drive twelve hours each way to save money and to give me flexibility in those cases when the launch scrubs until the following day. When launches are delayed for longer periods of time, I will leave Florida empty-handed and start over. I will have to impose on my colleagues to cover classes for me when the launch schedule conflicts with my academic calendar. In order to start this project, I will have to set aside the novel I’m already halfway through, a novel I’m expected to publish soon in order to qualify for tenure and keep my job, which is the sole source of benefits for my family. And I will have to impose more on Omar, the only local and NASA insider I know. All this might well turn out to be for nothing. But I’ve decided to try.

Over the following months, people will ask me what I expect to find by going to the last launches, and I will have to admit that I have no idea. I’ll find it when I see it, I tell them—or else, I won’t, and all this will have been a waste. I know I want to write about those places where the technical and the emotional intersect—like the smell of space, or the schoolchildren watching Challenger explode with a teacher aboard, or an adult woman hiding her tears in the cathedralic heights of the Vehicle Assembly Building, or a bored child in a movie theater watching a beautiful astronaut float in her sleep. I want to see the beauty and the strangeness in the last days of American spaceflight, in the last moments of something that used to be cited as what makes America great. I want to see the end of the story whose beginning was told by some of the writers I admire most. I want to know, most of all, what it means that we went to space for fifty years and that we won’t be going anymore.

CHAPTER 2. What It Felt Like to Walk on the Moon

The astronauts walked with the easy saunter of athletes…. Once they sat down, however, the mood shifted. Now they were there to answer questions about a phenomenon which even ten years ago would have been considered material unfit for serious discussion. Grown men, perfectly normal-looking, were now going to talk about their trip to the moon. It made everyone uncomfortable.

—Norman Mailer,

Of a Fire on the Moon

Southern Festival of Books: Nashville, Tennessee, October 10, 2009

Читать дальше