When she left her bed nine months later, her right leg was withered and ramrod-straight. The other children could not but notice it. They made fun of her at school, calling her Peg-leg. She dreamed of them at night, like foul-snouted coyotes circling ravenously, sniffing menacingly at her leg. She fended them off. She lashed out at them, but she did not cry. At first school was torture for her; later it became a place to practice self-defense.

Knowing how cruel children can be, her mother put extra layers of socks on Frida’s right leg to conceal its thinness. But she fooled no one. It was only the new, custom-made pair of boots that gave balance to Frida’s walk, if not to her character, which was already showing signs of defiance. The boots made her feel important; she was still only a child, but already she was allowed to wear them like a real young lady. She still kept them in her room, next to her favorite doll, the Aztec figurines the Maestro had given her and the papier-mâché skeleton. The boots were made of fine calfskin, the toes a shade darker than the rest. She remembered how long it took for the maid to lace them up and how she would wait patiently for her to finish. The boots took her back to the days when her father would take her for walks in the countryside. While he painted his watercolors, Frida would collect pretty stones, watch the butterflies, birds and insects.

That was the first time I remember feeling jealous. Not of the other, healthy children, but of all those winged creatures. Once, when a butterfly alighted on my shoulder, flapping its delicate wings, I suddenly burst into tears. I didn’t know what to tell my father. I didn’t know it was jealousy I was feeling. Why don’t I have wings? I asked him. He did not laugh.

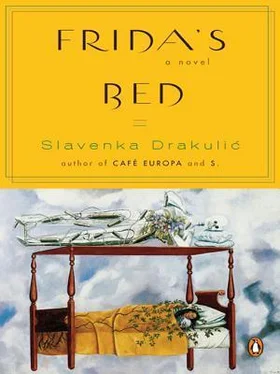

Perhaps it had been a sign of the bad times to come, thought Frida as she turned over in her bed that morning.

After recovering from polio, Frida, though still a child, quickly realized that her illness had left its mark. There were two ways she could cope with it: she could give up, accept her lameness as something shameful and hide away in the dark womb of the house — or she could fight back. She was forced at an early age to accept that she was different. But she had yet to learn the most important thing: how to turn her shortcoming into an advantage. That would take years.

When the other children made fun of her, she reacted with anger and defiance, but never self-pity. Young though she was, she refused to accept defeat, that was for Mama’s girls, like Kity and her friends. She had always despised tears or any sign of weakness. Since she was different anyway, she might as well be better, faster, stronger. She soon learned how to ride a bike. She climbed trees and swam faster than any of the other little girls who skipped rope and played hopscotch, taking care not to dirty their pretty little dresses. She was better even than Kity, who was not lame, but was not spunky either. And because she was different she could be bold and daring where other little girls could not, she could learn, for instance, how to wrestle or box. Her mother secretly felt sorry for her, but her father was fulsome in his support, telling her that she was better than the others because she was braver, that courage and intelligence were more important than not being lame and that she had both.

Racing around the nearby park on her bicycle, she felt as if she were flying. If only she could fly, she thought, then she would not need legs.

I could not escape the pity or the cruelty of others. Pity had a smell to it, I always recognized it because I had grown up with it. Because it had followed me all my life. Sometimes I thought I would gag from the familiar reek of sweat that soaked the air.

An old auntie, a friend of her grandmother’s, would sometimes come calling. She was short and round like a bread roll. She would waddle over to the sofa and sink into the cushions with a sigh, as if these few steps had left her exhausted, and perhaps they had. Then she would take out a fine batiste hankie and wipe her neck and throat. She would bring Frida sweets, the kind that came wrapped in silky paper so they wouldn’t stick to your fingers. In return, Frida would let the old lady hug her and stroke her hair with the hand that was not busy gesticulating and dabbing at her sweat, and the old woman would say, Poor, poor little thing! Then, on the verge of tears, she would heave an even louder sigh. She had a peculiar sour-sweet smell to her, a mixture of sweat, vanilla sugar and the mint tea the maid would serve, and also of something indefinable, unusual and strong, like tobacco, but different from the pipe tobacco that Frida’s father occasionally smoked. Once she had finished her afternoon tea, she would take out a little silver box, a snuffbox she called it. She would place a pinch of the dark powder on the crook of her finger, raise it to her nose and snort it. Auntie snorted snuff. Don Guillermo, big-boned and tall, would stand by the window and watch her perform this ritual, which little Frida found so fascinating. He did not approve of the child’s pretending to like it when the old lady stroked her head just so she could get the sweets, nor did he approve of the old lady’s pitying Frida every time she paid a visit. Once, controlling his irritation in front of the child, he could not stop himself from saying, Don’t keep telling her what a poor little thing she is, Tante. She looked at him in astonishment, as if the girl’s father had taken leave of his senses. But see how she limps, poor little thing, she said sadly. That’s just how it looks, said the father, and he walked out of the room, angry, she could tell by his step. Frida took the sweets and hobbled out after him.

In the warm late afternoon air that wafted in through the open garden doors, in the scent of the snuff that mingled with the fragrance of lavender, jasmine and the yellow rambling roses, she recognized the smell of pity. After the old lady left, her father told her that the most important thing was for her not to think of herself as a poor little thing. It had never occurred to her to do so. But she remembered that smell.

The morning light, still faint and diffused, slowly crept in under the dark curtains, circling the furniture and spilling across the floor.

Her nightgown was soaked with sweat, she was shivering, but she took comfort from the fact that, for the moment at least, she was awake and conscious. Because as soon as they gave her the injection, she would drift off into semiconsciousness again. Maybe she could even have a cigarette. But that would require an extra effort. She would have to lift her hand out from under the cover, reach for the cigarettes and matches on the night table, light one up and inhale. And then she would cough until she rued ever having made even the slightest movement. She could hear the birds singing outside. Soon Mayet would wake up and walk into her bedroom with the basin and towel. These morning rituals had become so pointless and tedious. She would rather rest and postpone the start of the day until later.

She tried to recall her life before polio, before her body had become such a burden, before she knew how hard it could be to walk. She remembered hiking in the nearby hills, running after her father and helping him carry his painting kit. Or going to the market with the maid, to mass on Sunday mornings with her mother‚ to school with Kity. Her body was not yet a hindrance to her when she walked. But after she recovered from the polio, her body assumed a new weight. Not just physically, she reflected, but metaphysically as well. It became as heavy as a rock that she was forced to drag along. After the accident, there was scarcely a second that she was not conscious of its weight.

She had to admit that there were also times when she knew the meaning of exhilaration and happiness — how else would she have found the strength to drag her body around? And so that morning she tried to recollect the days when it had been such a simple matter to wake up and get out of bed without anybody’s help.

Читать дальше