‘Mummy, what a lovely dinner!’

‘Well, it’s the first day of the holidays,’ said her mother cheerfully, ‘and I’ve just got three weeks’ work from Mrs Pendlebury Parker, so I thought we would celebrate.’

There was a bunch of marigolds in the centre of the blue and white table cloth, a constellation of small, glowing suns. There were crescent rolls, tinned tongue and salad, and a bottle of bright pink fizzy stuff for Rosemary.

‘There is ice-cream with stewed fruit afterwards,’ said her mother, ‘but hang up your things and wash first.’

‘Tell me about Mrs Pendlebury Parker!’ said Rosemary when her knife and fork began to move a little more slowly. ‘Is it nice sort of sewing, and can you bring it home with you?’

Stories of Mrs Pendlebury Parker and the splendours of Tussocks, her house which was just outside the town, were always a source of wonder to Rosemary.

‘I’m afraid I shall have to go there every day for the next three weeks,’ said her mother. ‘I’m so sorry to have to leave you for so long on your own, Poppet, but she does pay so well, I felt I could not afford to say no. I’m afraid it is largely mending linen, so I can’t bring the work home.’

Rosie let the blob of ice-cream on her tongue melt completely before she answered, and then she said as cheerfully as she could, ‘I shan’t mind really, I expect. How hateful for you to be sides-to-middling sheets, when you ought to be making beautiful dresses!’

Mrs Brown smiled. ‘Never mind, darling. Think of all the things I shall have to tell you when I come home in the evenings!’

‘And perhaps,’ said Rosemary, brightening, ‘you’ll be rich enough afterwards to buy one of those things for making your sewing machine go by electricity, and then you’ll earn so much more money that we shall be able to go and live somewhere else, where your ladies will come to you, instead of you having to go to their houses whatever the weather is like. And I shall dress in black satin and say, “This way, Modom!”’ Her mother laughed.

‘And I shall be able to say, “Mrs Pendlebury Parker,” I shall say, “No, I’m afraid I cannot make you twelve flannel nightdresses by the day after tomorrow. I never sew anything coarser than crêpe de chine!”’ They both laughed a great deal, and the meal ended quite cheerfully.

When they had finished, Mrs Brown had to go into the town to match some silks, so Rosemary cleared away and washed up the dinner plates. Next she put away her school things and changed into a cotton frock, and all the time she was wondering what she could do with herself for the next three weeks. Could she really do something useful, she wondered, as Mrs Walker had suggested? It had been rather unfair to call her a ‘great girl’, because she was rather small for her ten years. All the same, it would be wonderful, she thought, to earn some money without her mother knowing anything about it, and at the end of the holidays carelessly to pour a shower of clinking coins into her astonished lap!

‘The trouble is, I don’t know what I could do,’ she said to herself. ‘I can’t sew well enough. The only thing I can do is to keep our rooms clean and tidy. I always do that in the holidays when Mummy is busy. I can sweep and polish and wash-up.’

She rather liked the idea, and by the time she had done up the difficult button at the back of her cotton frock Rosemary had made up her mind. She would go out daily and clean.

Now she had a hazy idea that it would be necessary to take her tools with her, in the same way that her mother took her own thimble, needles, and scissors when she went out to sew. Dusters and a scrubbing brush would be easy, but Mrs Walker would not let her past the front door with a broom without going into a long explanation, and then it would no longer be a surprise.

‘Well, there is nothing for it,’ she said to herself, ‘I shall have to buy one for myself.’

After much rattling and poking with a dinner knife her money-box produced two and fivepence three farthings.

‘P’r’aps if I went to Fairfax Market I could find a cheap broom,’ she thought doubtfully. ‘It’s rather a long way, but I think I could get there and back before tea time.’

2

Fairfax Market

Rosemary put the money in her pocket and left a note for her mother; then she started off for Fairfax Market. This was held in the old part of the town in the cobbled market square. Because she imagined that two and fivepence three farthings was not very much money with which to buy a broom, she decided not to waste any of it on a bus.

She started resolutely off, only stopping occasionally to look in a shop window. But it was hot and dusty going. The pavements seemed to toast the soles of her feet through the rubber soles of her sandals. To make matters worse, one of the buckles came off. By the time she reached the market a slight drizzle was falling, and the clock on the Market Hall roof was striking four. Instead of the cheerful racket of people shouting their wares, of laughter and bustle, the stall-holders were already packing up. Rosemary went up to a stout woman who was stacking crockery which had been displayed on the cobbles.

‘Please,’ she said anxiously, ‘will you tell me where I can buy a broom?’

‘You can’t,’ snapped the fat woman without looking up. ‘Not now you can’t.’ Then she straightened herself with a grunt and looked at Rosemary’s disappointed face.

‘Never ask a favour of a fat woman when she’s bending,’ she said more kindly. ‘Leastways, not if you want a civil answer. Don’t they teach you that at school?’

Rosie shook her head, and the fat woman went on, ‘The market’s been closing at four on Mondays these last three ’undred years, leastways, so my old father told me. Never mind, cheer up, lovey! ’Ave a fancy milk jug for your ma instead?’

Rosemary shook her head again and went sadly on between the rows of dismantled stalls and piles of goods hidden under tarpaulins, already glistening with rain. The money in her hand was hot and sticky, but there was nothing to buy with it, let alone a broom, so she put it back in her pocket. She inquired again of a young man who was loading bales of brightly coloured material into an ancient car.

‘Please, do you know where I can buy a broom?’

But all he said was ‘’Op it, see!’ So Rosemary ’opped it.

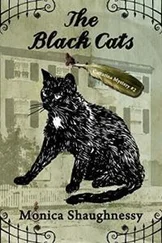

She wandered on among the drifting straw and bits of paper till she came to the end of the market, where the pavement began again. Here she found a little shop that sold newspapers and sweets and odds and ends, so she stopped to look in the window. She wondered whether to buy a toffee-apple or a liquorice bootlace to sustain her on the way home. The toffee-apple would last longer, but on the other hand she could eat a bit of the bootlace and use the rest as a skipping rope and still eat it later. She had just decided on the apple, because you cannot skip comfortably with a buckle off your sandal, when she felt something damp and furry rubbing against her bare legs. She looked down, and saw a huge black cat. Now Rosemary liked cats. If only Mrs Walker had allowed it she would certainly have had one of her own, so she bent down to stroke him. But the cat ran off and then sat down a few yards away and looked at her. Rosemary followed and tried to stroke him again, but the creature darted off for a few feet as before, and sat down to wash its paws. Rosemary laughed.

‘I believe you want me to follow you! All right, I will. I’m coming!’ So they went off in fits and starts, with Rosemary trying to catch the cat, who lolloped away as soon as she was within stroking distance. But although the cat did not laugh as she did, it was perfectly obvious that he was enjoying the joke as much as she was. She was just going to make a successful grab at him when she bumped into someone. It was an old woman.

Читать дальше