The elephant felt a terrible pain in her chest.

It was hard for her to breathe; the world seemed too small.

The Countess Quintet, after considerable and extremely careful consultation with her worried advisers, decided that the people of the city (that is, those people who were not invited to her balls and dinners and soirées) could, for their edification and entertainment (and as a way to appreciate the countess’s finely tuned sense of social justice), view the elephant for free, absolutely for free, on the first Saturday of the month.

The countess had posters and leaflets printed up and distributed throughout the city, and Leo Matienne, walking home from the police station, stopped to read how he, too, thanks to the largesse of the countess, could see the amazing wonder that was her elephant.

“Ah, thank you very much, Countess,” said Leo to the poster. “This is wonderful news, wonderful news indeed.”

A beggar stood in the doorway, a black dog at his side, and as soon as Leo Matienne spoke the words, the beggar took them and turned them into a song.

“This is wonderful news,” sang the beggar, “wonderful news indeed.”

Leo Matienne smiled. “Yes,” he said, “wonderful news. I know a young boy who wants quite desperately to see the elephant. He has asked me to assist him, and I have been trying to imagine a way that it could all happen – and now here is the answer before me. He will be so glad of it.”

“A boy who wants very much to see the elephant,” sang the beggar, “and he will be glad.” He stretched out his hand as he sang.

Leo Matienne put a coin in the beggar’s hand and bowed before him, and then continued on his walk home, moving more quickly now, whistling the song the beggar had sung and thinking, What if the Countess Quintet becomes weary of the novelty of owning an elephant?

What then?

What if the elephant remembers that she is a creature of the wild and acts accordingly?

What then?

When Leo came at last to the Apartments Polonaise, he heard the creak of the attic window being opened. He looked up and saw Peter’s hopeful face staring down at him.

“Please,” said Peter, “Leo Matienne, have you figured out a way for the countess to receive me?”

“Peter!” he said. “Little cuckoo bird of the attic world. You are just the person I want to see. But wait; where is your hat?”

“My hat?” said Peter.

“Yes, I have brought you some excellent news, and it seems to me that you would want to have your hat upon your head in order to hear it properly.”

“One moment,” said Peter. He disappeared from the window and came back again, his hat firmly upon his head.

“And now, then, you are officially attired and ready to receive the happy news of which I, Leo Matienne, am the proud bearer.” Leo cleared his throat. “I am pleased to let you know that the magician’s elephant will be on display for the edification and illumination of the masses.”

“But what does that mean?” said Peter.

“It means that you may see the elephant on the first Saturday of the month; that is, you may see her this Saturday, Peter, this Saturday.”

“Oh,” said Peter, “I will see her. I will find her!” His face suddenly became bright, so bright that Leo Matienne, even though he knew it was foolish, turned and checked to see if the sun had somehow performed the impossible and come out from behind a cloud to shine directly on Peter’s small face.

There was, of course, no sun.

“Close the window,” came the old soldier’s voice from inside the attic. “It is winter, and it is cold.”

“Thank you,” said Peter to Leo Matienne. “Thank you.” And he pulled the window shut.

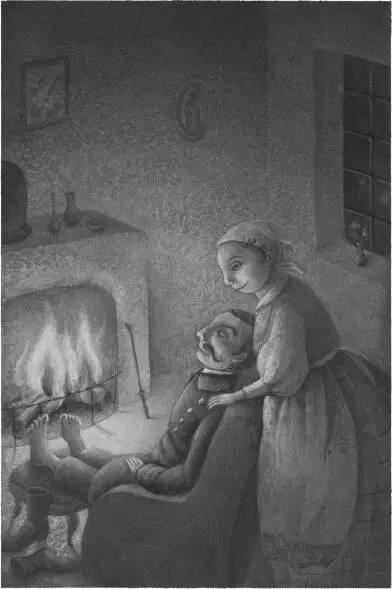

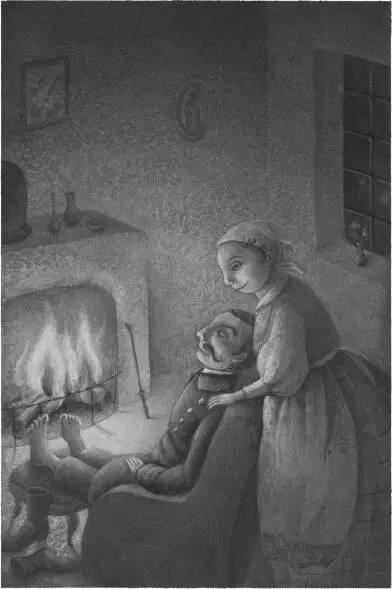

In the apartment of Leo and Gloria Matienne, Leo sat down in front of the fire and heaved a great sigh and took off his boots.

“Phew,” said his wife. “Hand me your socks immediately.”

Leo removed his socks. Gloria Matienne took them from him and put them directly into a bucket filled with soapy water. “Without me,” she said, “you would have no friends at all, because no one would be able to bear the smell of your feet.”

“I do not want to surprise you,” said Leo, “but, as a matter of course, I keep my boots on in public places and there is no need then for anyone to smell my socks or my feet.”

Gloria came up behind Leo and put her hands on his shoulders. She bent and kissed the top of his head. “What are you thinking?” she said.

“I am imagining Peter,” said Leo Matienne, “and how happy he was to learn that he could see the elephant for himself. His face lit up in a way that I have never seen.”

“It is wrong about that boy,” said Gloria. She sighed. “He is kept a prisoner up there by that man, whatever he is called.”

“He is called Lutz,” said Leo. “His name is Vilna Lutz.”

“All day it is nothing but drilling and marching and more marching. I hear them, you know. It is a terrible sound, terrible.”

Leo Matienne shook his head. “It is a terrible thing altogether. He is a gentle boy and not really cut out for soldiering, I do not think. There is a lot of love in him, a lot of love in his heart.”

“Most certainly there is,” said Gloria.

“And he is up there with no one and nothing to love. It is a bad thing to have love and nowhere to put it.” Leo Matienne sighed. He bent his head back and looked up into his wife’s face and smiled. “And we are all alone down here.”

“Don’t say it,” said Gloria Matienne.

“It is only that—”

“No,” said Gloria. “No.” She put a finger to Leo’s lips. “We have tried and failed. God does not intend for us to have children.”

“Who are we to say what God intends?” said Leo Matienne. He was silent for a long moment. “What if?”

“Don’t you dare,” said Gloria. “My heart has been broken too many times, and it cannot bear to hear your foolish questions.”

But Leo Matienne would not be silenced. “What if?” he whispered to his wife.

“No,” said Gloria.

“Why not?”

“No.”

“Could it be?”

“No,” said Gloria Matienne, “it cannot be.”

At the Orphanage of the Sisters of Perpetual Light, in the cavernous dorm room, in her small bed, Adele was dreaming again of the elephant knocking and knocking, but this time Sister Marie was not at her post, and no one at all came to open the door.

Adele awoke and lay quietly and told herself that it was just a dream, only a dream. But every time she closed her eyes, she saw again the elephant, knocking, knocking, knocking, and no one at all answering her knock. And so she threw back the blanket and got out of bed and went down the stairs in the cold and the dark and made her way to the front door. She was relieved to see that there, just as always, just as for ever, sat Sister Marie in her chair, her head bent so far forward that it rested almost on her stomach, her shoulders rising and falling, and a small sound, something very much like a snore, issuing forth from her mouth.

“Sister Marie,” said Adele. She put her hand on the nun’s shoulder.

Sister Marie jumped. “But the door is unlocked!” she shouted. “The door is forever unlocked. You must simply knock!”

“I am inside already,” said Adele.

“Oh,” said Sister Marie, “so you are. So you are. It is you. Adele. How wonderful. Although of course you should not be here. It is the middle of the night. You should be in your bed.”

“I dreamed,” said Adele.

Читать дальше