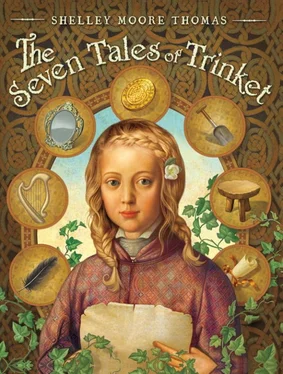

Shelley Moore Thomas

THE SEVEN TALES OF TRINKET

MY FATHER WAS A TELLER OF TALES. It runs in the blood, I think, for never have I loved anything so much as a story.

Except for my mother, of course.

I loved her well.

Her death was the worst thing I’ve ever known. Worse even than when my father left and never came back, for that has been almost five years past and that pain is now but a dull, empty ache.

My mother’s last breaths begin this story, for each story has a beginning. That is the first thing a storyteller must learn.

The night was cold and the wind whispered softly, rustling leaves and occasionally rattling the shutters of our small cottage. But the sky was so clear I could see every star, even the tiny ones. Despite the chill, I spent a lot of time outside looking at the sky. It was better than being inside our cottage, which held nothing but memories of happier times, and looking at my mother, sick with the wasting. Once she had been pretty, and even as she faced death, her eyes still held a twinkle.

“’Twas what your father first noticed about me: my eyes,” she had told me many times. “Lovely Mairi-Blue-Eyes, he called me.” Large they were, like sapphires, except that I had never seen a real sapphire, so I had to take her word.

I felt a hand on my shoulder. It was Thomas, the Pig Boy. “Old Mrs. Pinkett says to come in. She says…”

He did not finish the sentence.

Somehow, we both knew this night would be my mother’s last. There was so little left of her. Thomas squeezed my shoulder as I rose to go inside. I entered as quietly as I could, though the door creaked as a light wind rushed in beside me. Old Mrs. Pinkett nodded over at the bed where my mother lay. Her once soft arms now felt of brittle bone. But her eyes were more alive than ever.

“Sing for me, Trinket,” she whispered. So I sang for her the songs that we had made up in the years since my father left. They were not as beautiful as his, but we tried our best. For my mother always said that a house without music would be a lonely house indeed. When I finished, she raised a frail hand to my cheek.

“I’ve much to tell you, Trinket, and so little time,” she said.

“First, tell me, once more, tell me the beginning,” I said.

She drew a breath and began. “Once, a handsome storyteller whisked a fair maiden off her feet with his silvery words and amazing tales. He promised her a story each night and during the whole of their time together, he was true to his word. He carried her off with his words to places far away. And when she finally agreed to marry him, he took her to a little cottage by the sea where they were most joyfully happy.

“Their happiness was complete upon the birth of their babe. Our precious child , they called her, our delightful trinket , and that became her name. Your name: Trinket. The bard’s daughter.”

I smiled when she said my name.

Then she coughed. I turned to pour her some water, but there was Thomas, cup already in hand. I wanted to thank him but he disappeared as quickly as he’d come. My mother coughed again, this time even more harshly. I gave her water, but she had trouble swallowing. She tried to speak, but her voice rasped, sounding small and choked.

I took over the telling, willing my own voice to be strong.

“The traveling bard left one day when the girl was six, off on one of his storytelling, story-collecting adventures, for that was the life of a bard. He traveled from castles to villages, from coasts to mountains to valleys, telling the stories that were his own.

“He kissed the top of the child’s downy head,” I went on. My mother smiled, for I had added the downy part since the last time. “And called from the top of the hill, I shall see you with the season’s change .”

I hesitated, then continued.

“But he never came back.”

In a whisper, my mother took over the tale, adding the parts where perhaps he was kidnapped by pirates and forced to stay aboard a ship until he’d told ten thousand tales, or perhaps he had defeated a fierce dragon by putting it to sleep with a bedtime tale and had to tame all the dragons in the land with his stories.

Yes, she had told me time after time, that is why he could never come back .

My mother waited for his return. It took a long time for her heart to break completely. And when the illness came last winter, she had no fight left in her. A mended heart could have stood strong against the rampage of the fever and the wasting that followed. But a heart in little pieces had no chance.

She coughed and pulled me closer. “Trinket, my sweet girl. You have choices to make, you know.”

“I know.”

I could live with Old Mrs. Pinkett and learn the healing arts, but as much as I liked her, I did not feel the call in my bones to heal others. That is what Mrs. Pinkett said I should feel if I were to learn from her. My bones felt only empty.

I could live with Thomas the Pig Boy and his mother and learn the care and keeping of pigs and the occasional sheep, but the smell was too much. And though Thomas and I had spent most of our lives together, playing and getting into trouble, I’d no wish to be daughter to his mother. She was a rough woman with a sharp tongue that hurt far worse than getting a smack. How Thomas put up with it, I did not know.

My mother would want to know the direction I would take, Old Mrs. Pinkett had told me. It would help to ease her passing if she knew what my future might hold. But I was not so ready for my mother to leave. Not ready at all.

She looked at me, seeing more than I wished for her to. Her sapphire blue eyes squinted slightly. “I know what you are thinking.”

“I am not even thinking in this moment. You must be mistaken.” My lie sounded false, even to my own ears. The wind whispered and hissed through the cracks in the shutters as if doubting my words as well.

“You are thinking of him.”

“Him who?” Though we both knew exactly who him was.

My father.

“You want to go and find him.”

Did I? I had never spoken these words, but in her last moments, my mother knew the questions I had been too afraid to ever ask.

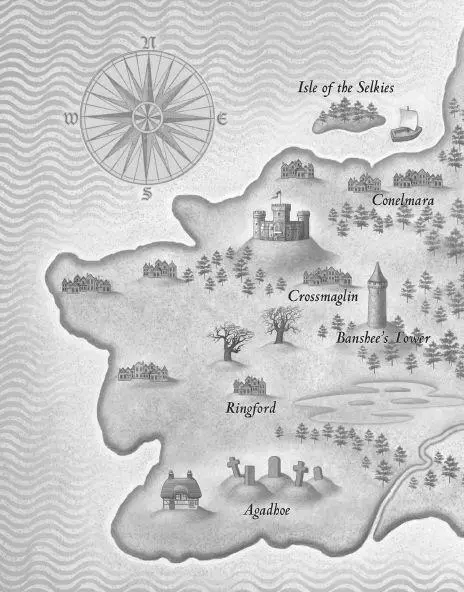

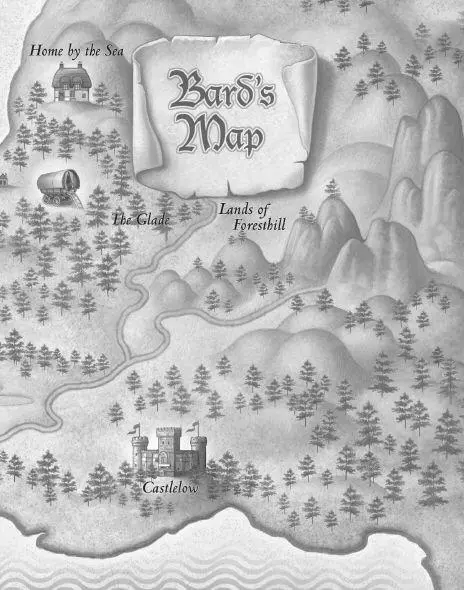

“There is a map, Trinket. A map in the old chest…” She coughed again and this one rattled throughout the room. A gust blew open one of the shutters and it creaked back and forth whilst the wind whistled around us, secretive and chilling.

There was no time to dally, so I asked, “What really happened to him, do you think?”

She was quiet and her breath did not come for a moment, causing me to think that perhaps she was gone, but then she sighed and closed her eyes. The flurry in the room calmed to a gentle breeze.

“I wish I knew.”

Those were her last words.

* * *

I cried for a whole week after she passed. I cried until the tears would come no more and my soul was empty.

Читать дальше