Seeing Clearly

The Lightning Thief is also about “seeing clearly”: the schools Percy has attended (six so far) and the various teachers he’s had, as well as his smelly unpleasant stepfather, have marked him down as a troublemaker and a no-hoper. When something goes wrong, it must be Percy’s fault.

And that’s because they don’t see the real Percy.

Nor, for that matter, does he see them very clearly: He’s unaware that his teacher Mr. Brunner is actually a centaur, that Mrs. Dodds is a razor-taloned Fury out for his blood, that his best friend Grover is a cloven-footed satyr, and that the three old ladies on the roadside are the Fates.

Later, he fails to see through the disguises the various gods or monsters adopt—sometimes until it’s almost too late, as when the Mother of Monsters, Echidna, along with her doggie-who-ain’t-a-doggie, tries to turn him into a smokin’ shish kebab.

Percy’s failure to “see clearly” extends to his “normal” life as well: His dyslexia, considered a handicap in our world, causes visual distortions. “Words had started swimming off the page, circling my head, the letters doing one-eighties as if they were riding skateboards,” he describes it in The Lightning Thief . In reality, the dyslexia is the result of Percy’s brain being hard-wired for Ancient Greek and is part of his uniqueness.

But most of all, Percy doesn’t see himself clearly.

Like the schools and society that have labeled him as some kind of maverick and failure, he sees himself in terms of those same labels.

In the Rags to Riches story, the true focus is not so much on growing up as it is one of its chief requirements: becoming aware .

It is learning to be conscious , learning to see clearly and wholly, that distinguishes these types of stories. Even Peter Rabbit manages to escape the dangerous farmer and the garden in which he eats and plays to his heart’s content (like any egocentric infant) only when he climbs up high to get a better view of things.

Attaining consciousness—awareness—is the true mark of the rebel, and the greatest danger for those in power, whether they be gods or parents. It is no coincidence that authoritarian regimes, like Saddam Hussein’s pre-invasion Iraq, seek always to control the media and to dictate what people can and can’t know.

Rags to Riches

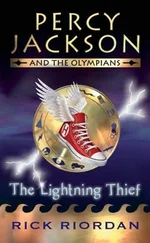

In his astonishing book The Seven Basic Plots , Christopher Booker outlines and explores the fundamental stories that have entranced, and continue to entrance, the human race. One of these is the Rags to Riches plotline. While many stories combine more than one of these plots ( Star Wars is both a Rags to Riches story and an “Overcoming the Monster” story, as is The Lightning Thief ), I want to concentrate on the Rags to Riches plotline, in which, as Booker puts it, “a young central figure emerges step by step from an initial state of dependent, unformed childhood to a final state of complete self-realization and wholeness”—in other words, the hero gains maturity throughout the journey, or rite of passage, that he experiences.

Why is this story, above all others, told so often?

The quick answer is that it is the only one of the seven basic plots that charts the life of a human being from the limited awareness of childhood to the discerning perception of adulthood.

The Rags to Riches story is also designed to show us the importance of learning through experience. It shows us the early days of life when no one in the story sees clearly; how this permits us to be easily ruled by others; how cruelty and abuse rule through ignorance; how trying to see clearly becomes a threat to this domination and in what way, by passing through various grueling tests in which a near death occurs. Throughout all this, new powers of maturity are gained, self-mastery is acquired, and a “happy ending” is defined as one in which everyone has begun to see more clearly than ever before. And as Booker points out, when people can see properly, they can move ahead and gain confidence and prosperity.

By contrast, this plot also shows how the great and fatal flaw of the dark figures in the story is always a kind of persistent or peculiar blindness, a distortion of vision, brought on by self-centeredness—that very trait that defines infancy and early childhood. The title itself tells us that the preoccupation in The Lightning Thief is with vision: Someone has stolen light—the very thing needed to see clearly! And the culprit? A god, of course. A god of war. A god of domination and darkness.

In this sense, we understand that the dark figures of the story are those who never grow up, who never see clearly and wholly, who remain blind and self-centered.

The Five Stages of Growth

The Rags to Riches plot generally progresses through five stages intended not only to chart the human journey but also the journey of that most rebellious of human traits: consciousness.

Stage 1: Initial wretchedness at home and the “Call”

Here we meet the young neglected hero and see the world he inhabits, a world of scorn and abuse (think of the Dursleys in Harry Potter). The importance of this stage is not just to show how things began but to draw attention to the difference between the hero/heroine and the darker figures around him or her—in Percy’s case his stepfather, his math teacher Mrs. Dodds, the nastiest girl in school who torments him and Grover, and the school system itself. Note that in mythological terms, the lowly hero/heroine is also the “diamond in the rough,” that which is overlooked and treated with contempt for appearing to be plain and inferior.

Yet what is significant here is that while the dark figures in the story rarely change at all, the hero also does not change as much as characters in other story types . . . and that’s because the Rags to Riches hero already possesses the traits that will one day make him or her exceptional . These traits are simply buried inside him, more or less invisible to the people around the hero, and to the hero as well.

The other crucial aspect of this stage is that we see the downside of not seeing clearly, of being in a state of limited awareness: Percy buys into society’s labels (believing himself to be a loser and troublemaker); he is exploited by his scumbag stepfather (he feels he has no power); he thinks there is something wrong with him, that he’s bad (everything keeps going wrong); and he doesn’t know what is going on or who people really are (he does not have the special knowledge or maturity he needs to “see” the bigger picture).

Stage 2: Out into the world, initial success

This is a kind of “dream stage” when almost everything goes right at last, in contrast to the next stage, though it also gives the hero time to start developing some of the skills he’ll need later on. In Star Wars, Luke learns how to use the Force from Obi-Wan Kenobi. In The Lightning Thief , Percy Jackson arrives at Camp Half-Blood and begins his training. Like all “orphans” in Rags to Riches stories, he is also trying to find out who he is and where he came from. This search for personal identity is a powerful force and usually focuses on the hero’s parentage. Here, Percy discovers he is the son of Poseidon, the lord of the ocean (interestingly, the ocean is usually a symbol of the unconscious and of the feminine).

During this stage the hero tries to grow up too quickly: becomes cocky, arrogant, or overly prideful, and thinks he is mature before he really is; he usually makes important decisions based on this false assumption. What success he finds at this point is based on some false power or outside agency (Aladdin had his genies).

Читать дальше