Nils stands beside the road as if he were frozen to the spot, and watches Maja stop on the other side of the low stone wall.

She looks at him. He looks back at her but can find no words, not even to say hello. The silence is made all the more unbearable by the joyous song of a nightingale rising from the ditch along by the wall.

In the end Maja opens her mouth.

“Have you shot something, Nils?” she asks cheerfully.

He almost reels backwards at the question. At first he thinks Maja knows everything, but then he realizes she isn’t talking about the soldiers. He has a shotgun; he’s usually carrying the hares he’s shot when he gets back to the village.

He shakes his head. “No,” he says. “No hares.” He takes a step backwards, feeling the weight of the little metal box in his rucksack, and says, “I have to... go now. To my mother, in the village.”

“Aren’t you taking the village road?” asks Maja.

“No.” Nils is still moving backwards. “I can get there quicker across the alvar.”

The words are coming more and more easily; he can actually talk to Maja Nyman. He’ll talk to her some more another day, but not today.

“Bye, then,” he says, and turns away without waiting for an answer.

He can sense that she is standing there watching him, and he walks directly away from the village road, counting up to two hundred steps, then he turns off and heads back down toward the village.

The whole time he can hear the faint rattle of the metal box moving around in the bottom of his rucksack, and he realizes he daren’t take it home with him. He must be careful with his spoils of war.

After a few hundred steps more, when the village road has disappeared behind the juniper bushes, a little pile of stones appears in front of him.

The old memorial cairn. It’s a marker Nils almost always walks past on his way to and from Stenvik, but now he goes over to it and stops. He looks at the pile of large and small stones, thinks for a moment, and looks around.

The alvar is completely deserted. The only sound is the wind.

An idea is growing within him, and he shrugs off the rucksack and sets it down. He takes out the box containing the gemstones, holds it in his hand, and stands right beside the cairn.

Almost directly to the east lies Marnäs church. Nils can see the church tower sticking up, like a little black arrow on the horizon. He orientates himself by the church tower, positions himself as if he were standing at attention, and takes a big stride away from the cairn. Then he begins to dig.

He lifts the top layer of turf in small pieces and then digs down into the ground with his hands and the German’s little knife. The rock isn’t far below the surface here; the layer of soil is shallow all over the alvar.

Nils scrapes away the soil to make the hole bigger, hacking and digging and looking around him all the time.

When he has made a broad hole in the ground, about a foot deep, Nils has already hit the rock, but it’s deep enough. He takes the metal box and places it carefully in the bottom of the hole, then lifts several flat stones from the cairn and builds a little vault around it. He quickly fills in the hollow, packing the soil down as hard as he can with the palm of his hand.

He devotes most of his time to replacing the pieces of turf on top of the soil — it’s important that everything looks the same as usual around the cairn.

It takes a long time to get the turf right, but in the end he gets up and looks at the spot from different directions. The ground looks untouched, he thinks, but his hands are dirty when he puts his rucksack back on.

He sets off toward home again.

He’ll tell his mother about the encounter with the Germans, he decides, but he’ll tell her carefully so she doesn’t get worried. He won’t tell her about the gemstones he’s hidden. Not yet, that will be a surprise for her. Right now the spoils of war are hidden treasure that only he knows about.

He finally climbs over the stone wall and is back on the village road, but closer to the village than when he met Maja. He’s almost back in Stenvik.

Before he reaches home, two men in heavy boots come up onto the road from the sea and trudge past him. They are eel fishermen, carrying a freshly tarred hoop net between them, their hands blackened.

Neither of them says hello; both look away when they are passing Nils. He doesn’t remember their names, but it doesn’t matter. Their rudeness doesn’t matter either.

Nils Kant is bigger than them; he’s bigger than the whole of Stenvik. Today he has proved that, during the battle out on the alvar.

It’s almost dusk. He opens the gate to his own house and goes into the silent garden, striding proudly up the stone path. The empty garden is flourishing and turning green. The grass scents the air.

Everything looks just as it did this morning when he left home to hunt for hares — but Nils himself is a new person.

Lennart Henriksson was standing next to Gerlof’s desk, weighing the plastic bag containing the little sandal in his hand, as if its weight might reveal if it was genuine or not. The fact that the shoe had turned up didn’t seem to please him at all.

“You need to tell the police about things like this, Gerlof,” he said.

“I know,” said Gerlof.

“Something like this needs to be reported straightaway.”

“Yes, yes,” said Gerlof quietly. “I just didn’t get round to it. But what do you think?”

“About this?” The policeman looked at the sandal. “I don’t know, I don’t jump to conclusions. What do you think?”

“I think we should have been looking in other places, not in the water,” said Gerlof.

“But we did, Gerlof,” said Lennart. “Don’t you remember? We searched in the quarry and all the cottages and boathouses and sheds in the village, and I drove all over the alvar. We didn’t find a thing. But if Julia says it’s his shoe, then we have to take this seriously.”

“I think it’s Jens’s sandal,” said Julia behind him.

“And it came in the mail?” asked Lennart.

Gerlof nodded, with the unpleasant feeling that he was in the middle of an interrogation.

“When?”

“Last week. I phoned Julia and told her about it... That was partly why she came to visit.”

“Have you still got the envelope?” said Lennart.

“No,” said Gerlof quickly. “I threw it away... I’m a bit absentminded sometimes. But there was no letter with it, and no sender’s name, I do know that. I think it just said ‘Captain Gerlof Davidsson, Stenvik’ on the front, and it had been forwarded here. But the envelope isn’t that important, is it?”

“There’s something called fingerprints,” said Lennart quietly, with a sigh. “There are strands of hair and a lot you can... Well, anyway, I’d like to take the sandal with me now. There could be traces on it too.”

“I’d really rather—” Gerlof began, but Julia interrupted him and asked, “Are you going to take it to a lab somewhere?”

“Yes,” said Lennart, “there’s a forensics lab in Linköping. The national police lab. They examine this sort of thing there.”

Gerlof didn’t say anything.

“Fine, let them have a look at it,” said Julia.

“Do we get a receipt?” said Gerlof.

Julia looked annoyed, as if she were embarrassed by her father, but Lennart nodded with a tired smile.

“Of course, Gerlof,” he said. “I’ll write you out a receipt, then you can sue Borgholm police if the lab in Linköping loses the shoe. But I shouldn’t worry if I were you.”

When the policeman left a few minutes later, Julia went out with him, but soon returned. Gerlof was still sitting at the desk, holding the receipt Lennart Henriksson had scrawled and staring gloomily out the window.

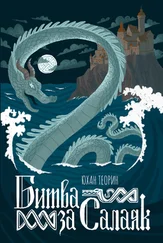

Читать дальше