Johnny was the only other CAY deputy at work that early, and we hit the scene twenty minutes later.

Abby Elder, the mother, was still in a blue terry bathrobe when she answered the door. Johnny walked in ahead of me and I saw him eyeing the front doorknob sadly — God knew how many times it had been touched by now. Abby’s eyes were red and puffed and her hair was still messed from sleep.

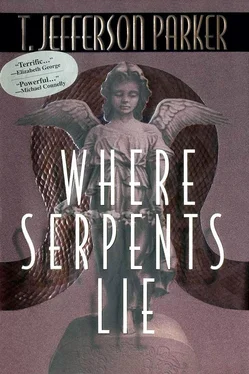

Two Irvine PD officers stood in the bedroom. They looked at me, then down at the bed. I followed their eyes to the thrown-back sheet and covers and the long translucent snakeskin lying lengthwise down the bed. It was papery and wrinkled and its two jaws lay loose and open. It was probably five feet long and four inches wide. I looked at the hideous thing, then back at Abby Elder, who stood with her arms around herself and a big piece of her bottom lip locked under her teeth. Fat clear tears rolled down her cheeks.

“What does he do to them?”

“Nothing, Ms. Elder,” I said. “He dresses them and lets them go.”

“He should be in prison.”

“He will be.”

“She’s my life. Brittany is my whole life.”

“We’re going to do everything we can to get her back to you.”

I told Johnny to start his crime scene work and took Abby into the living room. I wanted to hear every word she had to say. I told her to take it slowly, tell me the details as she remembered them.

While she talked she looked at me with eyes begging me not to fault or blame her. Parents blame themselves for everything bad that happens to their children. I can vouch from experience. So I interrupted her several times to assure her that this was not her fault in any way, but other than that I kept silent, took notes and let her tell me about the night that was, she said, easily the worst of her life.

“This is every worst nightmare I ever had,” she sobbed at one point.

“People wake up from nightmares,” I said. “You’re going to. So is Brittany.”

At the mention of her daughter’s name, a fresh river of tears poured down Abby Elder’s face. I said nothing.

Instead, I looked at the pictures hanging on the living room wall. They were school portraits of Brittany — a pretty, dark-haired girl with brown eyes and a mischievous grin. There was a pink ribbon in her hair. In another photograph she was posed with her mother. They both looked happy and healthy, like they had nothing but good things to do that day. I wondered again at the courage and energy it must take for a mother to raise a child alone. Or a father. A single parent, I thought. Like Pamela’s mother. Like Courtney’s. I realized something then, but I couldn’t quite grasp what it was. So I listened.

Her story was actually quite brief and clear: she had awakened at 6 A.M. as she always did on workdays, to her alarm. She liked waking up to a reggae station. She put on her robe, got a cup of coffee — the machine timer had it brewed up by five-thirty because she loved the smell of coffee in the morning. She poured in some milk and took the cup with her to peek in on Brittany. Usually, she said, Brittany would sleep until Abby was done with showering and dressing, around seven. But Abby always checked on her, first thing, or almost first thing, after she had that first cup of coffee going.

“And,” she said, blinking and looking down at the carpet She took a deep breath but didn’t look at me. “And when I opened the door and looked... she wasn’t there. She just... wasn’t there. Instead, that... thing was in her bed. Where she was supposed to be.”

The room was still fairly dark and it felt different, she said, so she turned on the light and overrode her shock a little, thinking that Brittany might be way under the covers, down by the foot of the bed, as she sometimes was. She wasn’t. Abby had pulled the bed away from the wall and looked under it. She’d flung open the closet, then run to the child’s bathroom. When she went back into the bedroom she felt the breeze and saw the window slid open and realized the screen was gone. She had screamed. Then she had raced to the kitchen and dialed 911.

“The room felt different because the window was open?” I asked.

“Yes. The wind coming through? I didn’t register it until I came back in.”

“Did it feel different for any other reason?”

She brought her red-laced eyes to me. “It felt like a room that something bad had happened in.”

I made a note of that. Abby said she’d looked through Brittany’s room again after calling 911. Then she looked on the patio and in her own bathroom, and, for reasons not rational, under the big cream sofa in the living room. She looked in the garage. She looked in the washer and dryer. She said she was standing in the living room crying when the Irvine officers arrived, and when she answered the door she was too distraught to even speak. Her gaze shifted to the floor again and I knew that Abby Elder was punishing herself for what had happened. She shook her head and buried her face in her hands.

I could see down the short hallway toward Brittany’s room where Johnny was photographing the bed with the shed skin in it. He’d already set his crime scene ribbon across the beginning of the hall, and stationed the Irvine cops on the other side of it. They stood there side by side, one looking back at Johnny and the other looking forward at me. They both looked spent: graveyard patrolmen on their last hour of the shift.

“When was the last time you checked on her?” I asked.

“Before I turned out my lights. It was eleven-twenty.”

Abby Elder’s words sounded detached and dreamlike now, as if delivered on her behalf by someone next to her.

I asked her if she had any relatives in the area.

She said her mother, up in Fullerton, maybe half an hour away.

“Why don’t you call her? See if she’ll come over and be here with you.”

“I... I think that’s a really good idea. Now?”

“Sure. We’re almost finished with this.”

I asked for a cup of that coffee, both because I wanted it and because I wanted to get Abby focused away from herself a little. For the next twenty minutes we talked about her life, job, habits, haunts, friends, acquaintances, routines, activities. Her family, her ex, her neighborhood. I was trying to find the intersection with Pamela and Courtney. I saw little Pamela in Orange — which was north of here; and I saw little Courtney down in San Clemente — to the south. Brittany was in the middle. None of their tangents crossed in any way that I could find. Until I looked at Brittany’s picture on the wall and began to understand what I’d almost understood just a few minutes ago. This was it: Pamela, Courtney and Brittany looked nothing alike. A blonde, a redhead and a brunette. Their mothers — Jennifer, Bridget and Abby — looked very much alike.

He’s not picking the girls, I thought: he’s picking the mothers. That’s why we haven’t connected the girls. It’s not they who catch his eye. It’s Mommy. That’s where we’ll find the plane of intersection.

“Abby,” I said. “Would you name for me, right off the top of your head, every group you’ve belonged to recently — church group, parents’ group, classes, workshops, seminars, social groups, clubs, unions, affiliations, anything? Everything? Please? Just take off and start naming.”

I’d asked Jennifer Clark and Bridget Simenon the same question, and I had their answers carefully recorded in the case files of Pamela and Courtney. But I knew I had been focusing on affiliations where the girls would be present. Now I knew that the girls came second. The mothers came first, to his eyes. It was a small candle in our room of darkness, but its light was warm and promising.

Читать дальше

![Джеффри Дивер - Where the Evidence Lies [A Lincoln Rhyme Short Story]](/books/403782/dzheffri-diver-where-the-evidence-lies-a-lincoln-r-thumb.webp)