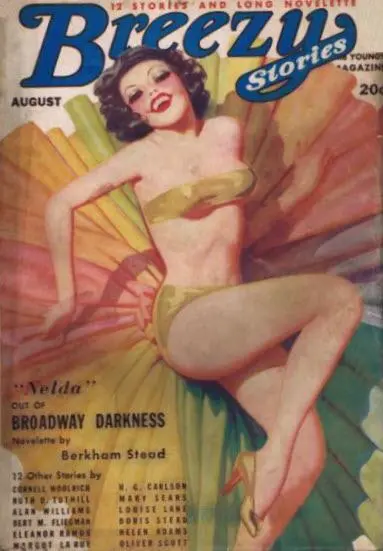

Корнелл Вулрич - A Treasury of Stories (Collection of novelettes and short stories)

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Корнелл Вулрич - A Treasury of Stories (Collection of novelettes and short stories)» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2018, Жанр: thriller_psychology, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A Treasury of Stories (Collection of novelettes and short stories)

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:2018

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A Treasury of Stories (Collection of novelettes and short stories): краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A Treasury of Stories (Collection of novelettes and short stories)»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A Treasury of Stories (Collection of novelettes and short stories) — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A Treasury of Stories (Collection of novelettes and short stories)», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

I took another look at Alice Colman’s regards to the statue and wondered why she hadn’t put her name down with it, and how she had come to be mixed up on her dates the way she had. And why a different address from her own. Of course the obvious answer was that she knew g.d. well what was taking place on that stairway below at the time, and was too nervous to know what she was doing. But she hadn’t acted nervous at all, she had just acted dreamy. So that probably wasn’t the answer at all. And just for luck I transcribed the thing into my notebook exactly as it stood in eyebrow pencil.

4/24/35/4 and then, 254W51. Wrong date, right hour, wrong address, no name.

“I take it all back, Johnny,” I said wearily. “Kick me here — and here. The guy did come up here after all — and right on top of what he did too.”

“But he didn’t write nothing — you looked all over them wind—”

“He didn’t come up here to write, he came to read.” I pointed at it. “He came to read that. Let’s go down. I guess I can keep my promise to General Lafayette down there after all.”

When I got ashore I halfheartedly checked Colman at the Tarrytown Apartments once more. No, neither Mr. nor Mrs. had come back yet, they told me after paging them on the house phone. I didn’t tell them so, but they might just as well have hung out a to-let sign and gotten ready to rent that apartment all over again. He wasn’t coming back any more because he was spending the night at the morgue. And she wasn’t coming back any more either — because she had a heavy date at 4. As for Scanlon’s Amboy Street address, I didn’t even bother with it. Have to use your common sense once in awhile. Instead I asked Information to give me 254 West 51st Street, which was the best I could make out of the tag end of her billet-doux.

“Capital Bus Terminal,” a voice answered at the other end.

So that’s where they were going to meet, was it? They’d stayed very carefully away from each other on the ferry going back, and ditto once they were ashore in New York. But they were going to blow town together. So it looked like she hadn’t had her days mixed after all, she’d known what she was doing when she put tomorrow’s date down. “What’ve you got going out at four?” I said.

“A.M. or P.M.?” said the voice. But that was just the trouble, I didn’t know myself. Yet if I didn’t know, how was he going to know either? I mean Scanlon. The only thing to do was tackle both meridians, one at a time. A.M. came first, so I took that. He spieled off a list a foot long but the only big-time places among them were Boston and Philly. “Make me a reservation on each,” I snapped.

“Mister,” the voice came back patiently, “how can you go two places at once?”

“I’m twins,” I squelched and hung up. Only one more phone call, this time to where I was supposed to live but so seldom did. “I may see you tomorrow. If I came home now I’d only have to set the alarm for three o’clock.”

“I thought it was your day off.”

“I’ve got statues on the brain.”

“You mean you would have if you had a—” she started to say, but I ended that.

I staggered into the bus waiting room at half past three, apparently stewed to the gills, with my hat brim turned down to meet my upturned coat collar. They just missed each other enough to let my nose through, the rest was shadow. I wasn’t one of those drunks that make a show of themselves and attract a lot of attention, I just slumped onto a bench and quietly went to sleep. Nobody gave me a first look, let alone a second one.

I was on the row of benches against the wall, not out in the middle where people could sit behind me. At twenty to four by the clock I suddenly remembered exactly what this guy Scanlon had looked like on the ferry that afternoon. Red hair, little pig-eyes set close together — what difference did it make now, there he was, valise between his legs. He had a newspaper up over his face in a split second, but a split second is plenty long enough to remember a face in.

But I didn’t want him alone, didn’t dare touch him alone until she got there, and where the hell was she? Quarter to, the clock said — ten to — five. Or were they going to keep up the bluff and leave separately, each at a different time, and only get together at the other end? Maybe that message on the statue hadn’t been a date at all, only his instructions. I saw myself in for a trip to Philly, Boston, what-have-you, and without a razor, or an assignment from the chief.

The handful of late-night travelers stirred, got up, moved outside to the bus, got in, with him very much in the middle of them. No sign of her. It was the Boston one. I strolled back and got me a ticket, round-trip. Now all that should happen would be that she should breeze up and take the Philly one — and me without anyone with me to split the assignment!

“Better hurry, stew,” said the ticket seller handing me my change, “you’re going to miss that bus.”

“Mr. Stew to you,” I said mechanically, with a desperate look all around the empty waiting room. Suddenly the door of the ladies’ restroom flashed open and a slim, sprightly figure dashed by, lightweight valise in hand. She must have been hiding in there for hours, long before he got here.

“Wait a minute!” she started to screech to the driver the minute she hit the open. “Wait a minute! Let me get on!” She just made it, the door banged, and the thing started.

There was only one thing for me to do. I cut diagonally across the lot, and when the driver tried to make the turn that would take him up Fifty-first Street I was wavering in front of his headlights. Wavering but not budging. “Wash’ya hurry?” I protested. His horn racketed, then he jammed on his brakes, stuck his head out the side, and showed just how many words he knew that he hadn’t learned in Sunday School.

“Open up,” I said, dropping the drunk act and flashing my badge. “You don’t come from such nice people. And just like that” — I climbed aboard — “you’re short three passengers. Me — and this gentleman here — and, let’s see, oh yeah, this little lady trying so hard to duck down behind the seat. Stand up, sister, and get a new kind of bracelet on your lily-white wrist.”

Somebody or other screamed and went into a faint at the sight of the gun, but I got them both safely off and waved the awe-stricken driver on his way.

“And now,” I said as the red tail lights burned down Eighth Avenue and disappeared, “are you two going to come quietly or do I have to try out a recipe for making goulash on you?”

“What was in it for you?” I asked her at Headquarters. “This Romeo of yours is no Gable for looks.”

“Say lissen,” she said scornfully, accepting a cigarette, “if you were hog-tied to something that weighed two hundred ninety pounds and couldn’t even take off his own shoes, but made three grand a month, and banked it in your name, and someone came along that knew how to make a lady’s heart go pit-a-pat, you’d a done the same thing too!”

I went home and said: “Well, I’ve gotta hand it to you. I looked at a statue like you told me to, and it sure didn’t hurt my record any.” But I didn’t tell which statue or why. “What’s more,” I said, “we’re going down to Washington and back over the week-end.”

“Why Washington?” my wife wanted to know.

“Cause they’ve got the biggest of the lot down there, called the Washington Monument. And a lotta guys that think they’re good, called Federal dicks, hang out there and need help.”

Clip-Joint

The taxi-driver slowed down invitingly, reached behind him, and threw the door accommodatingly open almost before the man’s arm had gone up to hail him. He said, “Yessir! Good evening!”, a courtesy he wasn’t in the habit of addressing to every customer. Skip Rogers ducked his head and got in. He took a tuck in each trouser just below the knee, leaned back against the upholstery, and sighed expansively. The uncommonly polite driver reached around a second time and closed the door for him. You wouldn’t have thought it was New York at all but for the serial number on the cab’s license plates.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A Treasury of Stories (Collection of novelettes and short stories)»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A Treasury of Stories (Collection of novelettes and short stories)» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A Treasury of Stories (Collection of novelettes and short stories)» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.