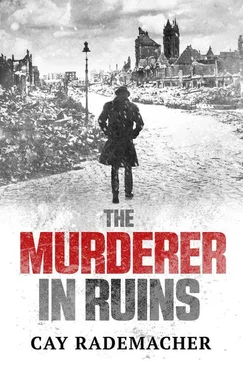

Cay Rademacher - The Murderer in Ruins

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Cay Rademacher - The Murderer in Ruins» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2015, ISBN: 2015, Издательство: Arcadia Books Limited, Жанр: Триллер, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Murderer in Ruins

- Автор:

- Издательство:Arcadia Books Limited

- Жанр:

- Год:2015

- ISBN:9781910050750

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Murderer in Ruins: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Murderer in Ruins»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Murderer in Ruins — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Murderer in Ruins», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The people piling in after them shoved Stave and Anna von Veckinhausen against the window on the far side of the carriage. The chief inspector fought back with his elbows, without turning round, then gave up and allowed himself to be pushed up against the woman who was going to help him catch the rubble murderer. He gave her an embarrassed smile.

‘Just a couple of stops and then we’ll be back in the fresh air,’ she said.

A shunt, the screech of steel wheels on tracks and a lurch as the tram turned a corner. Blows to the shoulders, the stomach, the weight of the man next to you swaying, a pain in the hand when somebody reached out to grab the same handhold as you. Muttered imprecations, growing louder. Nobody apologised, nobody looked at anybody else.

Stave said nothing. Every word could be dangerous. Nobody knew what the person next to you did in the war. There were cases of people cursing under their breath, then being stabbed by former veterans from the Russian front. Teenagers, who at the age of 15 were enlisted into the Hitler Youth and sent to the front for beating to death somebody who accidentally insulted them. Our society is a wasteland, the chief inspector thinks to himself. We detectives are just clearing up the rubble.

Stave couldn’t bring himself to say anything in the obscene crush. Anything he said would be overheard. You either cursed or shut up. In any case, what would I say to her, he thought to himself.

Fortunately the tram began to empty after the third and fourth stops – both unmarked amidst a wilderness of ruins, dozens of people clambering out. Where were they going, Stave wondered. Only now, when finally it was possible to move, a sweating conductor made his way across to them. Stave handed him a multiple journey ticket he had bought two weeks ago and to date had only used for one journey. Single tickets were no longer being sold: there was not enough paper. Stave rarely used the tram; he used the cash he saved to buy cigarettes he could exchange at the station for information from returning veterans. In any case walking strengthened his bad leg.

‘Two,’ he said to the conductor.

‘Generous,’ Anna von Veckinhausen said.

Good that she hadn’t used his title. If she’d said, ‘Chief Inspector,’ then everyone would have turned to look at him. And that wasn’t a pleasant feeling if you were in a carriage where at least half of those present had been trading on the black market.

‘Do you take the tram often?’ Stave asked needlessly, when there was finally enough space around them that he felt comfortable talking normally.

‘I’ve got used to it since I came to Hamburg.’

‘How did you get around before that?’

She gave him an attentive, slightly amused look. ‘Is that an official question?’

‘Private. You’re not obliged to answer.’

‘In a car. Or a carriage. Preferably on a horse.’

‘The home of a well-to-do family.’

‘A well-to-do home. I know what you’re thinking.’

‘What am I thinking?’

‘You think I come from some landed Junker family east of the Elbe. That it’s people like me who ruined Germany.’

‘Did you?’

She exhaled angrily. ‘We were nationalists, conservatives. But we never voted for Herr Hitler.’

The chief inspector wondered what she meant by ‘we’, but didn’t ask.

‘I get out here,’ Anna von Veckinhausen said, as with screeching brakes the tram came to a halt next to a blackened building facade half its original height.

Stave followed her without asking permission. They took a straight street that led between mountains of rubble, from which here and there remnants of wall protruded, reminding Stave of a long-drawn-out cross on a grave.

The Nissen huts stood at a crossing in the shadow of the old flak bunker: tin barracks erected along all four streets. The chief inspector counted 20 of them, with here and there the yellowy flame of candlelight shining through windows cut in the barrel-like sides, while others just sat there in the dark. The air was filled with the acrid stench of wet wood burning. Blue smoke rose from thin, twisted tin chimneys and gusted amidst the lines strung between the huts and hung with washing, long frozen solid. There was a smell of cabbage soup and wet shoes, and here and there a well wrapped-up figure coming from the tram passed them, pushed open a door in one of the barracks and disappeared.

In those few seconds Stave got a glimpse of the interior; rough wooden tables, a tiny stove in the middle of the hut, made of black cast iron. Clothing or sheets in every colour hung from lines strung across the interior in every direction, either washing or as makeshift walls, so that families could have the minimum of privacy in these barracks with no rooms.

Stave wondered what it must be like for someone who had grown up in a grand mansion now to be living in a communal barracks in the midst of ruins. He wondered if Anna von Veckinhausen was ashamed. Or if she was just lucky still to be alive and have a roof over her head, even if it was made of corrugated iron.

Anna von Veckinhausen walked up to the door of the Nissen hut in the centre of the crossing, a crossing with a completely undamaged advertising column standing in the middle of it. Every day when she left the hut Anna von Veckinhausen would find herself staring at the photos of the murderer’s victims. Maybe that was what led to her changing her statement, Stave thought in a moment of self-satisfaction.

A pair in dyed Wehrmacht greatcoats passed them, pushing a battered pram with a squeaking front axle. It didn’t look as though there was a child in it, more like a lump of wood, the chief inspector thought. That reminded him of his own unheated apartment and then he wondered what it must be like at night in these thin-walled barracks.

Anna von Veckinhausen speeded up her pace.

She wants rid of me, the chief inspector thought, ever so slightly disappointed. She doesn’t want to be seen with me here.

‘Thanks you for accompanying me,’ she said, as she reached the door in the front of the Nissen hut. ‘Do you think I need a bodyguard from now on?’

‘Why do you say that?’ Stave asked.

‘Because the murderer saw me.’

The chief inspector thought back to his conversation with the journalist from Die Zeit , and with a feeling of pained guilt turned his eyes up to the grey sky. ‘That is if the figure you saw was the killer. And if this figure did see you then he probably saw no more of you than you saw of him. He didn’t see your face, and certainly doesn’t know your name or address.’

‘I’m sure you’re right,’ she replied, but it didn’t sound as if she was convinced. She held out her hand. ‘Good night, Chief Inspector.’

She waited until he had walked off a few paces, before opening the door. Stave didn’t get the chance to look inside. He politely doffed his hat as a mark of farewell but the door had already closed with a tinny clang. He turned round slowly and set off on the long walk to Wandsbek, without limping. There was always the chance that she was watching him from one of the Nissen hut’s tiny windows.

He strode along for few hundred metres, trying not to think of Anna von Veckinhausen, or his son, or his wife, but just the case. The goddamn case.

A Hamburg industrialist who had made military equipment for the old regime and the pretty conservative-minded aristocrat from East Prussia – could there be a connection? The word ‘bottleneck’ on a piece of paper, and looted antiques, sold to the Brits. Was there a connection to be made there? A shrouded figure amidst the rubble. A long coat. The smell of tobacco. If he could trust the statement of a single witness. And could he trust Anna von Veckinhausen? Don’t think about her, not now. But then could he trust anybody? MacDonald – in the light of all the leads pointing to the British? Maschke, after the orphan child had pointed to him, and who was obviously hiding something? Ehrlich, who might well be on a personal vendetta and not really interested in finding the killer at all?

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Murderer in Ruins»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Murderer in Ruins» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Murderer in Ruins» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.