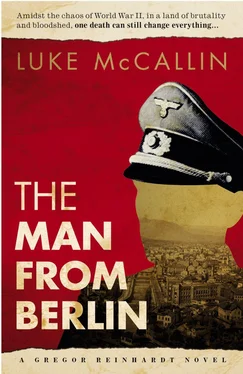

Luke McCallin - The Man from Berlin

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Luke McCallin - The Man from Berlin» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2014, Издательство: Oldcastle Books, Жанр: Триллер, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Man from Berlin

- Автор:

- Издательство:Oldcastle Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2014

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Man from Berlin: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Man from Berlin»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Man from Berlin — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Man from Berlin», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The Feldgendarme indicated a status board leaning against the sandbags. ‘Latest is the road’s clear as far as Rogatica. You’ll have to check in there for conditions farther on. Your destination?’

‘Foca.’ He proffered his movement orders at the Feldgendarme, who glanced at them before handing them back.

‘Safe trip, sir.’

Reinhardt nodded and took a deep breath, lowering the goggles back down. He shared a quick glance with Claussen, then squared his shoulders and looked ahead. Claussen hauled the wheel left and started down the road. The Feldgendarme watched them go until, flickering through the trees, the car vanished over a rise and the sound of its engine faded away into the still air of the mountains.

Part Three

THURSDAY

As they left the checkpoint behind, the road switchbacked up Mount Romanja, which lay athwart their route east, snaking through lands that had once been well inhabited, and past houses, alone or in hamlets, built of wood and dressed stone. Most were empty, and many were destroyed, walls collapsed in rubble and skewed timbers blackened and burned, gardens and fields overgrown and abandoned. These lands had been farmed and worked mainly by Serbs until the Ustase came, and most of the people had been slaughtered, rounded up in camps, or driven off into the arms of either the Partisans or the Cetniks. Signs of life were few. A spiral of smoke from a chimney, a handful of goats that twitched their heads nervously as the car went by, washing hanging from a line.

They rose higher up the rounded flanks of the mountain, the countryside flattening into view to their left. As always, when he saw it from the heights, Reinhardt found something about the Bosnian forest that registered on a level below that of rational conception. It spread out beneath and around them, a canopy of varied greens and shifting forms, rising and falling with the land hidden beneath it, and the earth was lobed by the frayed sweep and curve of hills, shy;fissured sometimes by flanks of exposed rock like the bleached karstic bones of the land.

The road swung across the rounded summit, through a forest sunk in gloom, the trees flowing against the blue sky that streamed overhead through a tracery of branches. They drove past mountain meadows across which marched the matchsticks of broken fences made to keep in livestock long gone. Big houses, like chalets or ranches, stood abandoned and gutted. When they emerged from the forest, at a point where the road swung down the other side of Romanja, they stopped for a break and to have something to eat.

Claussen had brought a flask of coffee and some bread and sausage, and Reinhardt walked to the edge of the road, sipping from a mug, and looked down across the country below them. The road wound away across flatlands to where a range of mountains broached the haze around their foothills, summits seeming to hang in the air like the brushstrokes of a painter. Standing there, he felt happy or, at least, resigned to a course of action. Perhaps they were the same thing, he mused, as he took the Williamson from his pocket, rolling it over in his hand and watching the play of light across the inscription. In any case, happiness did not mean conversation. Neither he nor Claussen had exchanged more than a couple of words since they left, but there was a comfort in that silence that he was loath to break for the sake of mere speech.

They did need to talk, though. Finishing his coffee and lighting cigarettes for them both, Reinhardt spread a map on the hood of the kubelwagen . The wind lifted one edge, and he weighed it down with the watch. ‘Have you ever driven down to Foca? No? Two possible roads there from Sarajevo. South, through Trnovo, Dobro Polje, then east to Miljevina. Or east, then south through Rogatica and Gorazde. That’s the road we’re on. It’s a fairly straight run through Rogatica’ – he pointed to the map southeast of their position – ‘to Gorazde’ – shy;farther south still – ‘and then along the Drina to Foca. Schwarz is aimed at the Partisans, here,’ he said, his finger circling the map south of Foca, over Mount Sutjeska. ‘But this is where we might have trouble. Brod.’ He pointed to a section on the map where the Drina, flowing north, made a sharp turn east towards Foca. Brod was where the southern and eastern roads met. A crossroads. If word of them had gone out, it would find them at Brod. ‘I don’t know of any way around it…’ He trailed off, looking at the map. ‘Nothing for it but to get there as fast as we can and then… play it by ear, I suppose,’ he finished, tossing the cigarette butt away, picking up the Williamson.

‘A favour, sir?’ Claussen motioned at the watch. ‘What’s the story with that? Never seen you with it before.’

Reinhardt ran his fingers over the inscription, giving himself time to surmount the reluctance within to talk of it. Only Brauer and Meissner knew the story. And poor old Isidor Rosen, but if anyone deserved to hear it now, it was Claussen. ‘It was that same battle in 1918 I got the Cross. That British redoubt. We fought a game of cat-and-mouse with the Tommies through the trenches for three days. I killed their officer, but not before he gave me this,’ he said, pointing at his knee, ‘and ended my war. Before he died, he gave me the watch and… asked me to give it back to his father if I survived the war.’ He paused, remembering suddenly, vividly, the viscous slide of mud, the latrine stench, the spatter of men across the bottom of the trenches. ‘I put it down to things a dying man says. But then the war ended and what he said stayed with me. I wrote to his father. We met. Spoke of his son. I offered him back the watch, but he said to keep it.’ Which he had, the watch taking on a significance that, after all this time, even Reinhardt himself was not sure of anymore. Only that it reminded him of a chance meeting of kindred spirits, a short space of time when he could be something other than the creature he was turning into, and because that Englishman was the last man he killed in that war, and that was worth remembering.

He weighed it in his hand, hesitating, then pulled the file from his backpack. ‘This is what it’s about. The evidence against Verhein.’ He explained the case, outlining what they knew and suspected, Claussen’s eyes moving from the file, to him, and back.

‘You can’t leave that lying around,’ Claussen said when Reinhardt had finished. He took a crowbar from the tool kit and levered the spare tyre away from its rim. ‘Under here,’ he said, voice strained. Reinhardt pushed and shoved the file under the tyre, against the inner tube. When it was done, they shared a blank look, a shared complicity that needed no words.

They set off again, descending steeply down the side of the mountain until the road emerged onto the flats, and Claussen opened the throttle and put the car on the road that arrowed straight across a wide, empty prairie, where the light undulated over a wash of grass runnelled winter pale and spring green. Gradually the foothills ahead emerged out of the haze, and the flats ended, the road sliding its way down into a deep canyon, down to where Rogatica nestled in its valley. The road took them past a destroyed hamlet, past an Orthodox church with its steeple blown off, the remains of its walls skirted in rubble, and through scarred neighbourhoods that showed the signs of much fighting, until they found the German headquarters.

A Feldgendarmerie officer informed Reinhardt that the road to Gorazde was backed up with traffic, and movement was slow around the bridge over the Praca. As they drove slowly back out, the town seemed sunk under a slough of decay and abandonment. Bullet holes pocked the walls; many houses were destroyed, and more burned out. Charcoal scrawls on some of the walls showed crosses, Catholic and Orthodox. Once, a Star of David on a house where the doors and windows gaped open. What few people he saw seemed stooped over, whatever their age, their eyes elsewhere. There were Serbs among them, mostly old women in black headscarves and black dresses who walked with a bandy-legged shuffle. Reinhardt could feel the fear in the town. As in the lands around Sarajevo, Rogatica’s Serbs had mostly been deported, massacred, or fled to the hills.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Man from Berlin»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Man from Berlin» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Man from Berlin» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.