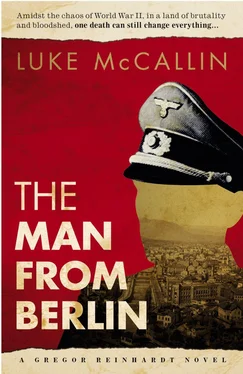

Luke McCallin - The Man from Berlin

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Luke McCallin - The Man from Berlin» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2014, Издательство: Oldcastle Books, Жанр: Триллер, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Man from Berlin

- Автор:

- Издательство:Oldcastle Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2014

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Man from Berlin: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Man from Berlin»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Man from Berlin — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Man from Berlin», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The priest shook his head, and his mouth firmed a little. ‘Not regularly. Without wanting to speak ill of the dead, and without wanting to take anything from her achievements, I must say that Marija’s behaviour left something to be desired, Captain.’

‘You know your ranks, Father.’

‘Oh, only sometimes. I’ve been known to mix my sergeants with my colonels on occasion,’ the priest replied.

‘Father… ?’

‘Father Petar,’ he said.

‘What time is the first mass on Sunday?’

‘At seven o’clock.’

‘Is there another service?’

‘Yes. At ten.’

‘Did you serve either of the masses?’

‘I was there, yes. At both of them.’

‘Father, did you notice if there were any Germans in the congre shy;gation?’

‘We get a lot of German soldiers in here. Many, these past few days. From the barracks just up the road. Praying, for success mostly.’

‘Success in what?’

‘The coming offensive, of course. Against the Partisans. The archbishop gave a most rousing sermon on it just this Sunday.’

Reinhardt had met Archbishop Saric once and, as an intelligence officer, read translations of his newspaper articles. The man was a rabid Ustasa, a committed fascist. He had also read some of the tawdry poetry the man produced, paeans of praise to Pavelic and his ilk, venomous tracts against Jews and Serbs. The way it had been explained to him, Saric was one of the instigators behind the mass conversions to Catholicism that were often forced on the Serbs by the Ustase. Just before they were hacked to death and dumped in mass graves.

Petar brushed down the front of his cassock, then stood up. ‘If you will excuse me, Captain? I have things to see to.’

Reinhardt wanted to get out of there before he became maudlin, or said something and regretted it. Not that he would be sorry for what he said. He would be sorry to have lost control of himself and said it. That, as Carolin would say, he would dare to express an opinion outside a police case. But he had not yet got what he came for.

The two of them walked down the aisle to the entrance. ‘Your German is very good, Father.’

‘Thank you, Captain. I spent some years studying for the priesthood in Bavaria. A most pleasant time.’ There was a moment of silence, the church drinking up their words. ‘And will you be taking part in the coming attack, Captain?’

Reinhardt shook his head. ‘No. Nothing quite so rewarding for me.’

‘Perhaps not anymore,’ Petar said. He motioned at Reinhardt’s Iron Cross. ‘But once it was.’

‘Thank you, Father. You have been most helpful.’ Reinhardt paused, looking back into the church. There really was nothing here anymore for him. Such a long road he had walked from the days of the boy he was, the boy he was brought up to be. Of the comfort he had once taken in the rote and ritual of the church, war, the years he had spent policing the filth and squalor of Berlin, and of watching his wife pulled away from him, had driven a wedge between then and now. ‘You must excuse me, Father,’ he said, with a smile meant as self-deprecating. ‘God and I have drifted quite far apart, but I like to think we were once close enough.’ He opened the big door and stepped outside into bright sunlight.

Petar followed him out. ‘God is never far from you, my son. You only have to reach out to him wherever you are. But it is funny how often I hear such similar things from your fellow soldiers.’

‘Who said what to you, Father?’ Claussen was standing just outside, his hands clasped loosely behind his back.

‘That many of you feel that you have drifted too far from our Lord.’ Petar paused, looking down at the flagstones that lined the church’s entrance. ‘I talked not long ago, Sunday in fact, and again yesterday, with an officer who felt like that. A very erudite man who had a very Catholic upbringing. A most remarkable knowledge of the Bible. We talked of much. He seemed… troubled. Borne down by a great weight.’

‘Well, if he was heading for the front, I suppose that’s only to be expected before battle.’

‘Yes, indeed. Doing God’s work is never easy on mortal men.’ Reinhardt had heard this kind of speech in the trenches. Us against them. God with us. Except here, it had taken on a measure of virulence he had never known. ‘No, it was not fear of battle. It was something else. Some inner demon he needed to exorcise. A fear that there was no way back for him. For those like him. We spoke much of forgiveness, and absolution. I offered him confession, but he refused.’

‘Perhaps he knew its limits.’ Petar frowned at him. ‘The limits of forgiveness,’ Reinhardt repeated. ‘What some of us have seen, and heard, and done, here in this country, will remain with us as long as we live.’

The priest smiled, but something seemed to shift behind his face, and for a moment Reinhardt caught a glimpse of someone else – shy; something else – behind his eyes. ‘I am sure it must be difficult, my son. But what you do is for a great cause. The Serbs. The Jews. Communism. These are most terrible afflictions. They must be swept away by men of courage and iron conviction. What you do in that cause, you will be forgiven.’

‘Father. There is perhaps one way you can help me.’

‘Tell me.’

‘Father, please think about this. Did you notice if any of the Germans who came to mass on Sunday, or since, acted strange?’

‘Strange, Captain?’

‘Nervous. Withdrawn. Panicked. Perhaps someone acting un shy;towards. Someone who seemed distressed. Or perhaps a new face… ?’

Petar frowned, shook his head. ‘I am not sure what you are getting at, Captain.’

‘May I tell you something in confidence? Yes? I have a reason to believe Marija was killed by a German soldier. And I have reason to believe that soldier may well have come here. Perhaps to confess. Perhaps to seek solace in prayer. Of course, the confessional is sacrosanct. But, perhaps, did you notice anything in church that Sunday?’

The priest’s eyes had gone flat at Reinhardt’s words. ‘What are you alleging, Captain?’

‘Nothing, Father. I am following up a line of inquiry. A feeling. Marija’s murder was horrible but her killer arranged her body as if she were at rest, afterwards. It seemed to me an act of remorse. And that such a man might seek… solace… in a place like this.’

‘I had read the Partisans were to blame for Marija’s death.’

‘Perhaps,’ said Reinhardt, noncommittally. ‘But for instance, I would be more interested in hearing about that soldier you talked with.’

‘No, Captain. You will not get that from me. I know what you Nazis have done to men of the faith. You will not hound that man for it, nor for his doubts.’ Reinhardt made to speak, but Petar cut him off. ‘Enough, Captain. I feel you have misled me. That you manoeuvred me into speaking of such things.’

It sounded so much like what Stolic had said in the officers’ mess that Reinhardt blinked. ‘I am sorry you think that, Father.’

Petar nodded, his eyes considering. ‘Well, even if I cannot applaud your line of reasoning, there are enemies all around, Captain. Where we least expect them. And even if you have, as you say, drifted far from your faith, go with my blessing.’

He touched Reinhardt on the shoulder. It felt like something caustic, and something seemed to come apart then, deep inside. Reinhardt was not sure what it was, only that something small, but something important, broke. Snapped. ‘You know, this medal,’ he said, jerking his thumb at his Iron Cross. ‘I got it taking a British redoubt at Amiens, in France. 1918. I attacked it, and then I defended it. I lost nearly all my men. At the end, there were just a few of us standing. Three, in fact. We all got the Iron Cross. One of them was a Jew. His name was Isidor Rosen.’

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Man from Berlin»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Man from Berlin» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Man from Berlin» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.