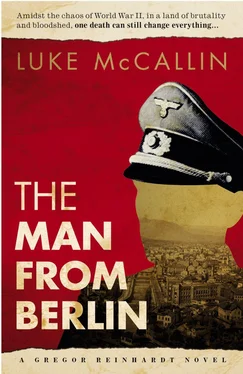

Luke McCallin - The Man from Berlin

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Luke McCallin - The Man from Berlin» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2014, Издательство: Oldcastle Books, Жанр: Триллер, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Man from Berlin

- Автор:

- Издательство:Oldcastle Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2014

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Man from Berlin: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Man from Berlin»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Man from Berlin — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Man from Berlin», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Reinhardt liked to think he was at least somewhat self-aware. He was a man whose formative years were spent in strict discipline and war. His father, a university professor, was a stern taskmaster who instilled in his son two perhaps contradictory ideas: a sense of duty to the state and people, and a respect for learning and independence of thought that constantly brought him into trouble with the university’s rectors and eventually forced him from his post. From him, Reinhardt inherited also his taciturn nature. Although he had a keen mind, he was not free with his opinions. Carolin would often chastise him, not for not having a mind of his own, but for keeping it, and his temper, too firmly under control.

She sometimes resented the influence Meissner had over Reinhardt but knew she could not fight it. The debt Reinhardt felt to Meissner was not one he ever thought about repaying. Meissner was a father figure to him who had saved his life several times during the war and from penury after it. She appreciated, although could not fully understand, the deep ties of loyalty and respect that bound them together, and she learned to find a place in that relationship. With Brauer, though, it was different, their two families coming from similar left-wing working-class backgrounds.

As he sipped his coffee, Reinhardt again thought back to the end of 1938, to his return to the colours and the start of the journey that had led him, via Norway, France, Yugoslavia, and North Africa, to where he was now. Reinhardt knew he had been a good policeman. It had been a surprise and a revelation to him how much he had enjoyed it, the security and respect it afforded, after those bitter and tumultuous years immediately after the war. The chance to channel all that anger and frustration from the war into something else, something constructive. But his fall from grace with the Nazis had been rapid, especially once he had refused transfer to the Gestapo for the second time, after he had clashed repeatedly with the new men they were pushing into the police, but more often with the men he had known for years who suddenly, overnight, expressed sympathy or outright support for Hitler and his ideals. He was pushed off the homicide desk and began a descent through the various departments, then out of Alexanderplatz into the suburbs, until he was running missing-person investigations. Which, seeing as just about all missing persons were Jews and just about all of them had been made missing by the people who employed him, was about as low as a detective could go in those days.

But even then he was still of interest to the Gestapo, and by June 1936 he knew there would not be a third offer. They would just move him. There was a lull during the Olympics when, for a few weeks, the city almost seemed to return to normal. Reinhardt was even reinstated back to homicide, but when the Games were over, it all came lurching back. That summer, the Nazis amalgamated the Kripo and the Gestapo with the intelligence agency of the SS and the Nazi Party – the Sicherheitsdienst – and there was no longer any distinction between the forces of the state and those of the Party. He became desperate in the autumn of that year to find a way out.

There was one more reprieve, at the end of the year, when he was posted to Interpol in Vienna. The Nazis were desperate to maintain a semblance of professionalism, and Reinhardt had a good reputation and contacts in England and France. He was their ‘face’ in Interpol. It was a sop, and he knew it, but it got him away from them, and they left him alone for a while. Carolin’s health even seemed to improve, but Vienna’s charms wore off fast as the city began the same downward spiral as in Berlin. After nine months there, the farce of Interpol was over as the Nazis moved it to Berlin, and Reinhardt went back into Kripo.

He muddled through that winter, keeping his head down, working nights, taking sick leave, all the while continuing to try to do his best, and clever enough to realise his best was only serving the Nazis. It was then, he knew, his horizons began to narrow, when he began measuring his days against the least he could do to get through them. The shambles of those months made him realise he was a man with few convictions in life, and he found himself with little or no desire or willingness to fight for the few he had. That realisation was horrifying to him. He held to the need to keep working to pay for Carolin’s treatment as a justification to stay on the job, but as her condition worsened, and as the work became increasingly surreal in the juxtaposition of formal procedure, extreme violence, and breathtaking political chicanery, he took steadily to drink.

Almost as soon as they returned to Berlin, and against Reinhardt’s express wishes, Friedrich joined up and Carolin, increasingly sick and worn out by the constant struggle between father and son, faded away and died. And then, at what seemed the lowest point, Meissner stepped in and arranged, through his contacts, a transfer to the Abwehr. shy;Reinhardt accepted even though the army held no more attraction for him, and the oath to the Fuhrer stuck in his throat, but it got him out of the police and away from the Nazis. The mental weight he had borne for several years eased.

Reinhardt was left only with the friendships of Meissner and Brauer, who had himself quit the force in 1935 after a violent altercation with his new commander. As a rambunctious working-class man with strong left-wing leanings, Brauer was instinctively hostile to the Nazis but smart enough to keep his head down. A self-confessed ‘simple’ man, Brauer had no illusions about his abilities to resolve a crisis of conscience, so he decided not to have one. From his position in the Foreign Office, Meissner’s motivations remained a mystery to Reinhardt, something that, when he thought about it, still gave him cause for concern.

What it all meant to Reinhardt, he realised more and more, was that he had no reason to do any of the things he did anymore. In the first war, he was a young man. Told to fight for the Kaiser, and for Germany, he did so to the best of his abilities, which in the end were considerable, and, truth be told, he had never been as alive as during those days of iron and mud. He would never be younger, never be fitter, one of the elite. But in reality he fought for Brauer, and Meissner, and all the others who shared the hardships of that war, and the riotous peace that followed. All those men from different walks of life, professions, persuasions, and convictions. Lives like threads that came together in one place and time to form one particular pattern of experiences, a unique combination shared by no one else. This time around, he had nothing and no one to fight for, and no one to fight alongside. No one to guard his back, as he once guarded theirs, and so he skulked through this war, keeping his head down, staying in the shadows.

It had been a long time since he had thought of anything like this, and he wondered whether it had done him any good. He knew he was lonely. Sometimes he even revelled in it. He knew he had not been true, really true, to himself for many years. He even knew when it first began, when he had first avoided his own eyes in the mirror. It was the time in 1935 they received the news about Carolin’s cousin. Greta was disabled and had been transferred to one of the new sanitoria. A few months later they received word she had died. He knew, though… As a policeman, you heard things.

The last excuse for carrying on and muddling through had been Carolin, and she was gone, and so the question he could not avoid answering much longer was, what made him keep going the way he was? Serving a cause he detested, in a uniform he hated, in an army he could not respect, with men he did not think he could fight for, feeling his convictions falling away one by one. He knew that collaboration and resistance came in many forms. He knew collaboration was not necessarily immediate, coerced, or unconditional, just as he knew resistance was not always instant, fervent, or inflexible. Knowing this gave him no comfort, and he knew that however much he had tried to hew to some kind of middle path, he had done both over the last few years.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Man from Berlin»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Man from Berlin» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Man from Berlin» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.