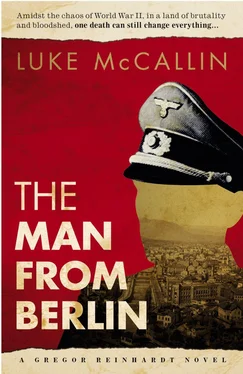

Luke McCallin - The Man from Berlin

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Luke McCallin - The Man from Berlin» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2014, Издательство: Oldcastle Books, Жанр: Триллер, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Man from Berlin

- Автор:

- Издательство:Oldcastle Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2014

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Man from Berlin: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Man from Berlin»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Man from Berlin — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Man from Berlin», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘I did warn you, did I not?’ Reinhardt jumped, startled. He had been so lost in his thoughts he had forgotten the doctor, standing quietly just a few feet away. ‘About these people?’

‘Who is he? The man they’ve got?’ asked Reinhardt.

‘There are two of them. One is a waiter. The other is his uncle. Both Serbs, although the waiter is half Croat.’ Reinhardt shook a cigarette into his hand, offering one to Begovic. He lit his, finding his hand shaking. He let the match go out, clenching his fist hard for a moment, before lighting another one for the doctor. Its flame pitched Begovic’s pasty pale face into sharp relief and woke answering glints in his thick spectacles. The match flickered out, and they were plunged back into that peculiar deep gloom dusk sometimes brought on.

‘What have they really done?’ asked Reinhardt around a deep lungful of smoke. He felt more than saw Begovic look at him, the pause as the doctor obviously wondered how much to tell him.

‘The uncle is a member of the Communist Party. His name is Milan Topalovic. They say he’s one of the Partisans’ contacts in the city. The police have had their eye on him for a while. What is it you policemen often say? “Motive and opportunity”? Unfortunately for him, Topalovic lives in Ilijas, not far from Ilidza. They’ve witnesses – including that old Austrian woman, Frau Hofler – who said they saw him, several times, near Vukic’s house. So he had the opportunity, apparently. And he’s a Serb, allegedly a Partisan, and Vukic hated both, so that’s motive. Apparently. The waiter’s just a boy really. They used him to get to Topalovic. He’s his only relative. They said if Topalovic confesses to the Vukic killing, they’ll let the boy go.’

Reinhardt finished his cigarette and tossed the butt into the road. ‘Thank you, Doctor. I wish you a pleasant evening.’ There was a foul taste in the back of this throat, and he wanted to be away from there.

‘Wait,’ said Begovic, coming after him. ‘You’re walking? You didn’t bring a car?’ Reinhardt shook his head. What little light there was ran up and down the frames of Begovic’s glasses as he turned his head from side to side. ‘It’s not safe for you to walk alone. Not even here. I will come with you. I’m going your way in any case.’

Reinhardt smiled, somewhat bemused that this little man thought to protect him. Then he tensed as a shape suddenly loomed out of the shadows. The man exchanged a few words with Begovic in Serbo-Croat. Reinhardt could not see him well, only the gleam of his eyes above the shape of his beard as he listened to the doctor. He nodded, reluctantly, it seemed, and stepped away. Begovic smiled as he answered Reinhardt’s unspoken question. ‘That’s Goran. You saw him yesterday. My driver cum assistant cum handyman. He doesn’t like me walking about after dark.’

‘Your friend is right, Doctor. It will be curfew any minute now. You should not be out.’

Begovic patted his jacket pocket. ‘I have a doctor’s permit.’

Reinhardt inclined his head courteously, putting his heels together. ‘In that case, it would be my pleasure, Doctor.’

The two of them walked in silence down to the end of the street, then left on Kvaternik. There was some street lighting here, shining creamy from lamps atop wrought-iron posts that stood along the quai, on the side nearest the river. Without speaking, the two of them crossed over and proceeded down towards Bascarsija, following the little pools of light winding down the road and around the corner. The shrunken river trickled quietly past them. There was something calming about walking. It was something Reinhardt seldom was able to do anymore, and the doctor was a strangely comforting presence. He was obviously fairly well known as he tipped his hat several times to people he passed as they hurried to get off the street before curfew, stopping once to talk to a woman with a little boy. He tickled the boy under the chin as he said goodbye, but the child only had eyes for Reinhardt. Big, wide eyes over a solemn mouth, the sort of face that expected the worst from people like him. Reinhardt looked away, suppressing a shiver of memory.

As the boy and his mother left, Begovic caught Reinhardt looking at him. He gave a little smile, then let his eyes slip, looking over Reinhardt’s shoulder at the opposite bank. He took a couple of steps over to the parapet that ran along the pavement. ‘You know, I was born just across there. In Cumurija.’ He looked down at the water. ‘We used to play down there. I can remember the Austrians building this, it was called Appelquai in those days. Very exciting. All that machinery. We used to play on the building site all the time; it drove the workers crazy. They would thrash us if they caught us, but it never stopped us.’ He gestured with his head across the river. ‘It used to flood all along and over there, quite regularly. I remember once, we were washed out of the house. It was the most exciting day of my life.’ He smiled at the reminiscence.

‘That’s a nice memory,’ said Reinhardt, more out of politeness than anything else. He hesitated a moment, wondering if he should be polite and offer a memory of his own, but he had nothing like that to offer. His childhood had been happy enough, but austere in its way; school, the church, duty, holidays once a year at Wismar on the Baltic.

‘Then the Austrians strengthened the other bank too, and it never flooded again. This place’ – he gestured down at the river – ‘became too dangerous to play in. Because of the new banks, the waters would rise too fast and too quickly.’ Begovic looked up, then around and behind him. ‘This city and water have always gone together, you know. There’s the valley, and the Miljacka. There’s the Zeljeznica, and the Bosna. The water flows through in the way it wants. Sometimes gently. Sometimes not. Like life. The Ottomans understood that, I think. All the Austrians could do was dam it, and channel it. Make it work for them and call it progress. Which,’ he sighed, ‘I suppose it was, in a way.’

They carried on walking up to the Emperor’s Bridge, which led back over the Miljacka to the barracks, where they stopped. Reinhardt waved away a pair of policemen on foot patrol. He looked up at the night sky. ‘You know,’ he said, ‘there are times I hate this place. The mountains. The streets. They seem to hem you in. You move and move and never get anywhere. Whichever way you turn, there’s always a wall.’

Begovic looked up as well. ‘Walls have doors, Captain. And windows. Have you been to Travnik? No?’ He smiled, running his eyes up and along the roll of Trebevic against the night. ‘Now there is a town squeezed in between its mountains. I can see how you might think that of Sarajevo, Captain, but I don’t see walls, or confinement. My city is a flower. A rose, in the shelter of her mountains.’ He looked up at Reinhardt. ‘This is my city, Captain. Mine. And she is beautiful.’

Reinhardt offered his hand, and Begovic took it after a moment. For some reason, Reinhardt was absurdly grateful that the doctor had not looked around to see if anyone might be looking before shaking the hand of a German soldier. ‘Thank you, Doctor,’ he said. ‘For your help, back there. I do apologise for my behaviour.’

‘Think nothing of it,’ replied Begovic. He paused. ‘If it can help, I can tell you Topalovic will not suffer much more. It will soon be over for him. For them both.’

Reinhardt’s mouth twisted. ‘Yes. A show trial and an execution. Very quick, if it’s done properly.’

Begovic blinked at him past his thick glasses. For a moment, it seemed to Reinhardt he wanted to say something else. Share something. ‘I wish you a good night, Captain. Until the next time we meet.’ He tipped his hat and was gone, a small, thin shape disappearing into the night.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Man from Berlin»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Man from Berlin» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Man from Berlin» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.