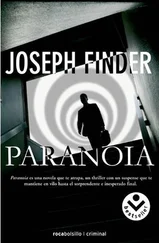

“I know all about you. You’re an interesting guy.”

I took a few shallow breaths, the best I could do.

“A man of paradoxes, I’d say. I’m familiar with your army records. I know what you did at Kunduz. The blood on your hands.” He shook his head again, and I couldn’t tell whether it was with disapproval or admiration.

He was talking about an episode in my past that I never discussed and preferred to forget.

“You do what you have to do,” he said. “You understand that, I can tell.”

“What do you want?”

“Just a little talk. We’re both busy men. We’ll keep this brief.”

“Okay. How about getting these cuffs off me?”

He nodded. “Sure. Soon.” He scuffed the toe of his brown calfskin brogue at the edge of a little creek of blood that was already starting to dry. “You know, in our line of work, there’s the sheep and there’s the shepherds. Guys like us, we’re the shepherds. We take care of the sheep. We protect them and make sure they live quiet, safe lives. Isn’t that really what they pay us for?”

I looked at him and said nothing.

He went on, “You and me, we don’t have an issue here. You may think we do, but we don’t. We’re like Germany and France — mortal enemies during the Second World War, and a few years later they’re trading partners. History of the world.”

“Do you have a point?”

He smiled. “We may do things differently, you and me, but ultimately we’re on the same side. The problem comes when clients — civilians — distract us. Set us against each other. There’s no reason for us to be at each other’s throats.”

“Is that right.”

“Look, Heller, you have your soft targets. We both know that.”

I just looked at him.

“There’s that woman who works for you, Dorothy something. There’s that nephew you’re really close to. The reporter from Slander Sheet. Hell, there’s even your mother, back in Boston. Soft targets.”

“Don’t even think about it, Vogel.”

“Man, I hate like hell to be talking like this. We should be working together, what I’m saying. Keeping the sheep safe.”

“Uh-huh.”

“You don’t want to be on the wrong side of me, Heller. We work this out, same time next year I’ll be sending you clients.”

“Uh-huh.”

“We don’t? Get yourself a black suit. You’ll be going to a lot of funerals.”

His cell phone rang, and he took it out of his pocket. “Vogel,” he said. “Yeah. Got it. I’m on my way.” He turned around, called out, “Rafferty, let’s go.” Then to me he said, “I’m sorry, I’ve got a meeting.”

He took out one of his metallic business cards and slid it into my shirt pocket. He waved vaguely at me, at the chair and the zip ties and everything. “We’ll give you some time to think it over.”

For a long time I sat there, zip-tied to the aluminum chair, thinking.

Vogel had left me alone in the empty warehouse, probably figuring that it would take me most of the day to get free. Maybe several days. I’d been bound with an excess of zip ties, one looped to another, which made it particularly challenging.

Not impossible, though.

Or so I told myself.

Unfortunately, I couldn’t use Vogel’s metallic business card, since I couldn’t reach my shirt pocket. I looked around the room, poring over the metal desk and coat tree and floor, looking for scissors or knives or anything sharp. The desk had a drawer, and that demanded a closer look. So how to move around? My ankles were zip-tied to the front chair legs. I shifted my feet and discovered I had a little bit of play. Enough for me to lift my heels and push against the ground with my toes. That moved the chair only a few inches, though, and I had twelve or fifteen feet to travel to the desk drawer. But it was something. The journey of a thousand miles...

A kind of dazed calm settled over me, like a blanketing fog. A very useful sort of calm. Once I was helping my nephew, Gabe, assemble a fiendishly complicated play-set model of a hospital, and he cried out in frustration. That was when I taught him how to let the calm wash over you, and to focus on one piece at a time, breathing in and out, placid, calm . It probably took the two of us three hours to assemble this damned hospital, but high-strung, short-tempered Gabe stayed with it, and when the hospital was finished, he glowed with pride. So whenever he was faced with something perplexing and intricate, a physics problem set or a difficult math assignment, I would say to him, “Remember the hospital,” and he’d instantly smile and nod, as if to say, I got this . When I’d see him about to blow his stack over an impossible jigsaw puzzle, I’d just say “hospital,” and he’d smile and nod and try harder.

Now I said to myself hospital, and I smiled. I can do this. It’ll be arduous and slow, but I can do this. I made myself enter the zone. Calm . I lifted my heels, pushed off with my toes, scraped the chair legs another two inches closer to the desk drawer. Two down, one hundred and seventy-eight to go.

My cell phone rang in my pocket.

As I slow-scuttled along the floor, the phone ringing, I worked on my hands. They were looped to each other at the wrists, and then each loop was connected to the chair’s vertical struts. If you thrust in a downward direction with enough force, you can snap the cable tie’s locking head and free yourself. But that wasn’t an option.

Lift heel, press toes, and shove. Another two inches closer. Nothing was impossible. Hospital .

I had to get the hell out of here.

The phone continued to ring. I counted thirteen rings, and then it stopped for a moment, and then it started to ring again. Insistently, it seemed. Someone was trying to reach me with some urgency. Mandy? Dorothy?

Only then did it occur to me that my fingers were free to wiggle and move, and that was something.

Working by feel alone, I tugged at one of the cable ties with my fingers, a loop that connected the loop around my wrists to one of the struts. I was able to pull it around so that its locking head was nearest my fingers.

Now I inserted a fingernail into the tiny plastic box that forms the lock. Inside that little box is a pawl, a pivoting bar that engages with the notched end of the strap and locks it in place, keeps it from moving. With my fingernail I was able to pry the pawl upward to release the tension. Then, tugging with my fingers, I loosened the cuff, pulling and pulling until the end of the strap came loose.

Success! It felt like a major victory, like winning an Olympic gold medal. I didn’t think about the fact that my wrists were still tightly bound together and my ankles were still looped onto the chair legs. That was negative thinking and wouldn’t help me. Focus on one tiny victory at a time. Hospital .

The phone stopped ringing.

I crabbed the chair along the floor toward the desk drawer, another couple of inches.

Now I was able to grab the other loop with my scuttling fingers, pulling it around until I grasped the locking head, then I probed it with the fingernail of my middle finger until I felt the little locking bar. I pushed it up with my fingernail while, with the fingers of my other hand, I tugged at the strap and managed to pull it loose. My hands, though bound, were now free to range around behind my back. That was something.

Get the hell out of here.

I scraped a few inches more. I looked at the desk drawer and wondered what implement it might contain. Maybe scissors, maybe a sharp letter opener, maybe even fingernail clippers. Anything that could cut through the nylon straps and free me. Even a paper clip would be useful.

Читать дальше