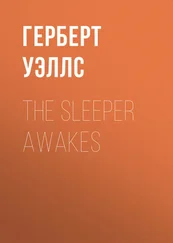

As I walked along the seafront, past the outdoor, seawater Jubilee Pool, feeling the first drops of rain on my face and licking flakes of pastry off my fingers, I scanned the faces I passed. It was instantly obvious as soon as a figure appeared in the distance that it was not Lara. Everybody was too old, or too young, or too fat or too tall; and anyway, if she were alive, she would be miles and miles away from here, the town in which Guy’s body had been discovered.

The coastline stretched away in both directions, crinkled and craggy. The sea was wild, the wind getting up. I turned my back on Newlyn and changed direction, heading instead towards the castle of St Michael’s Mount, cut off from land by the high tide, pushing my bike back to the station.

I fed the cats, made us both a cup of tea, and went online with Laurie, moody and suspicious, at my side. I looked up everything I could possibly find about Lara (there was nothing new, though a couple of newspaper sites were already bearing photographs of me clambering over that gate, and I hoped no one I had ever met would see them). I called Penzance police, to the annoyance of the man who answered the phone.

‘But,’ I told him, ‘I think there was someone else involved. You should be looking at all the passengers, tracking every one of them down. One of them did it, not Lara.’

He was almost polite.

‘We are of course pursuing every angle and talking to every passenger,’ he said. Then he made me get off the phone, quietly but ruthlessly, and I knew he saw me as a nuisance caller who was one of the hazards of answering the phone at the police station.

The press and the internet were interested in Lara and Guy for now, but soon the next story would come along. Lara’s body would be found, or she would be caught, or she would never be found. Those were the only three possible outcomes.

‘I want her to be all right,’ I told Laurie.

‘She’s not, though.’ His voice was flat. ‘And you know it. Whether she did it or not.’

‘I know. Shall I open some wine?’

He laughed. ‘Oh! Drink with me for a change. That’s good of you, my darling.’

‘Look, Laurie. There’s something I’m thinking about doing.’

‘What?’ The anxiety in his voice made me backtrack instantly, as I had known it would.

‘Oh, it’s nothing really. Look. Let’s have a drink. There’s some of that soup left over, too.’

He did not reply. I could not meet his gaze. There was only one bottle of wine in the house, and because I had drunk the nice one with Alex, it tasted rough. I could remember buying it: it had cost me £3.49, and it tasted cheaper than that.

All the same, cheap red wine was soothing in a way, and I sat on the floor in front of the wood burner, wearing my thick cardigan, jeans and chunky socks, and tried to work up the courage to share my plan. Ophelia came and rubbed herself against me, and Desdemona walked straight up to Laurie, who ignored her as he always did. He was ignoring me, too. I spoke to the cat instead, inside my head so he wouldn’t hear.

‘It’s none of my business,’ I told her. ‘There’s nothing I can do. All I can do is let it go.’

‘You don’t want to, though,’ she countered silently. ‘You want to know.’

‘Well, yes. I do want to know. I want to know what really happened.’

‘Well,’ said Ophelia, clambering on to my lap so I had to lean right back on my hands, and trampling me down until I was a suitable seat. ‘Why don’t you go to London and see what it looks like at that end?’

‘I could do that. Couldn’t I? Who would look after you guys?’

She sat on me and started purring. Her contribution to the conversation was over.

‘It would probably beat sitting around having conversations with a cat,’ I said, but her eyes were closed. When a cat doesn’t care, it doesn’t care.

In the middle of the night, I jerked awake. Laurie stirred next to me.

‘You’re obsessed with that woman,’ he said.

‘Shh,’ I told him, and he went back to sleep.

I was imagining someone cracking up. It had happened to me, years ago, and my cracks were showing now, more so every day. It was catching up. Perhaps that was what I had recognised in Lara, and what she had seen in me. Maybe that was why we had struck up a casual conversation, then spent the rest of the day together, drinking, talking intently.

I was amazed that the situation with Laurie, our odd set-up, had lasted as long as it had. Laurie never left the house. I could not live like that for ever.

I could suddenly empathise with a person running away on the spur of the moment, leaving everything behind and making herself invisible. It was, after all, possible that Lara might have done that. The papers had established the train’s schedule, the places where it stopped in the night to prolong its journey so that it reached Cornwall at a time when people might want to be setting off into the world. There were many of them.

She could have stumbled on the real killer, and turned and run away. I could imagine her panicking, her pulse racing faster and faster until she suddenly knew that she had to get out, immediately. The train could have been pulled in at a siding somewhere. No one had been watching: whatever had happened, that had been established. She could have climbed out of a window and vanished, terrified and unable to think straight.

She could, just possibly, have melted away at Reading: they thought Guy was killed at around the time the train stopped there. There was no one who looked like her on the station’s CCTV, but the cameras did not capture every passenger getting out at every door. The killer could have got on there, or got off there, or taken Lara off with him.

I slipped out of bed and crept into the study, and closed the door. When I switched the light on it dazzled me for a second, and made everything, all the boring paperwork of a modern life, look harsh and almost sinister.

She would not have stopped in London, if she had fled back there.

My passport was filed under P in the big metal filing cabinet. I pulled the drawer out so hard that it gained its own momentum and smashed into my leg, making me gasp.

There was nothing there. A few other things beginning with P were in there (contact details for a painter, an envelope of photos that I could not bear to look at), but there was no passport. I took everything else out and checked through it. Still no passport.

It had been there. I had not taken it out.

Laurie could have hidden it to stop me leaving. I would ask him, and I knew that I would be able to tell instantly from his face if he was lying. It would not have been his style. He would not hide my passport to keep me at home. He kept me at home with his presence.

If it was not him, however, there was no one else.

I thought about it. Nobody came upstairs in this house. No one was left alone in this room for the time it took to open a filing cabinet and retrieve a passport that was filed under P. Nobody at all. We had not been burgled. No one had even been to the house. Had they?

I sat on the floor and tried to work it out.

chapter eighteen

My bag was next to the door. I had almost nothing with me: everything I was taking fitted into a largish shoulder bag and a canvas handbag. The shoulder bag had been my father’s, long ago when there was such a person in my life. It was black, plasticky faux-leather, with a sturdy strap, and it was the only suitable receptacle I owned. It held the very minimum of clothes and toiletries.

It was the end of the day, almost dark outside and an odd time to be setting off.

I stood in front of Laurie before I went, and tried, again, to explain it to him. He looked back at me without a word. I hated it when he did that. In the end I walked away. He and the cats would take care of each other. I had left the cats lots of food, and had filled the fridge and the cupboards with everything that any of them could possibly need.

Читать дальше