Well, that’s all for now, darling. You’re in my mind and soul every waking moment.

In a few minutes, I’ll be turning off the light and slipping into bed again. Your letter will soon be touching my naked breasts.

Eternal love, darling.

Rosamund

What he did with the letter, first night he had it, was wait until his pal in the upper bunk was snoring, and then he took the letter and wrapped it around himself and made love to it, his fluids running into her delicate handwriting, becoming one.

After leaving the McNally place, I went to a drugstore where I bought some headache powder and drank a milk shake and looked through a science-fiction magazine. Then I went back to my little temporary hutch.

A motel room at mid-afternoon is an especially lonely place. With all their earnest drunken noise, the night people at least lend the place a festive air. But afternoon is wives on the run from rickety marriages, the kids in tow with dirty faces and sad frantic eyes, missing their daddy and yet hating him at the same time for how he treated mommy; and traveling salesmen wearing too much Old Spice and knowing far too many dirty jokes; and afternoon lovers from insurance agencies and advertising firms and department stores, giving each other quick hot sex of the sort their marriage partners gave up on years ago.

I saw samples of all these types passing by my window as I sat in the armchair, talking on the telephone, yellow pad on my knees, telling a friend of mine all about Mr. Tolliver.

“You want to know everything about him?” Sheila asked.

“Everything.”

“It’ll take me a little while.”

“I know.”

“He’s prominent enough that I think you could probably pick a lot of it up at the library. I really hate to charge you these rates, but it’s how I make my living.”

Sheila Kelly costs half as much as other computer search services I’ve used yet apologizes constantly for her prices.

“You’ll find out things I’ll never find in the library.”

Sheila was one of that new breed of human beings who spends half her life using a computer as an extension of her mind. Mike Peary had used her on several investigations and told me the information she’d turned up had helped him resolve the cases in a day or so. I’d had similar luck. Sheila performs hacking services that are not, strictly speaking, legal. But they sure are useful.

“Why don’t you give me your number?”

I gave her my number.

“Is that a motel?”

“Right.”

“Is it a nice place?”

“Well, the toilet flushes anyway.”

She laughed. “My husband and I stayed in a place like that in South Dakota once. It was like Motel Hell. We could only get one station on the TV and that was a local show that had pro wrestlers performing between country and western singing acts.”

“Well, this isn’t quite so bad.”

“You probably won’t hear from me till tomorrow.”

“Whenever.”

Ten minutes later, after stripping down to my boxer shorts, I laid down on the bed and opened up my Robert Louis Stevenson book.

I read until I got drowsy and then I napped for a while.

When I woke up, the sunlight was waning behind the curtains. A car door opened and chunked shut. Hearty laughter, man and woman. The night people were arriving.

I went into the bathroom and washed my face and combed my hair and when I came back out I picked out a shirt and trousers for my visit to Jane Avery’s tonight.

Then I looked down and realized that my bare feet had stepped in something that I was tracking across the rug.

I turned on the lamp and looked down at the stains I’d made. I raised my foot and turned it so I could see my sole, which I daubed at. Something sticky.

My eyes moved back up the trail I’d left. It stretched from where I stood to the closet door.

I went over to the closet and looked down. So much for the sharp eye of the detective. I’d walked past the small puddle beneath the door without noticing it until I’d accidentally stepped in it. No doubt about it. The Detective League of America, or whatever organization it was that detectives belonged to, was going to kick me out.

The closet door was louvered and dusty. I opened it carefully, on dry hinges that creaked, and looked inside at my clothing hanging from the rod that had been positioned at eye level. A string attached to a light socket above hung in front of my face. I gave it a tug. The naked bulb was burned out.

From here, below the line of shirts and trousers, I could see only a pair of legs from the knees on down. The shoes were tasseled and expensive cordovan loafers. The trousers appeared to be dark blue and hand-tailored. But I wasn’t going to learn much this way. I pushed all my attire to the right side of the small dusty closet for a better look.

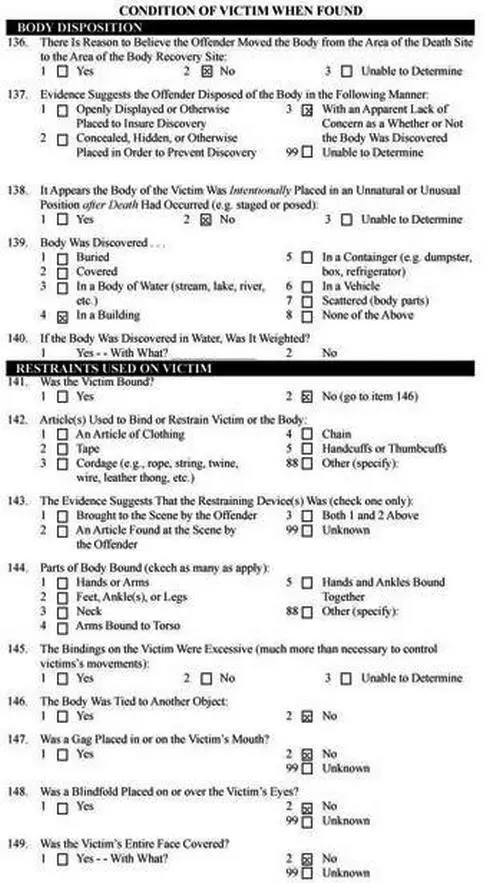

Even though I’d only seen him once, and then from a distance, I recognized the handsome and imperious face of Sam Lodge. He was still handsome, still the sneering art instructor and antique-shop owner but his charm was gone. The large butcher knife that had been shoved deep into his chest, almost to the hilt, lent him a violence that no amount of charm could have disguised anyway. The killer had shoved him up against the back of the closet so that his neck appeared broken, head resting at an awkward angle on his left shoulder. His blue eyes stared without interest at some point in the room behind me.

I closed the door and stood for a long moment trying to figure out what he’d been doing in my room in the first place. We hadn’t exactly been the best of friends. But even so, the enormity of death, of extinction, took me down for a few moments. After my wife died, I’d felt the same way, knowing that never again would she ever exist, not on this world nor on the billions of worlds filling the universe, never exist again no matter how remarkable were the discoveries of future science, never touch others with that special loveliness and grace and quiet self-effacing wisdom that had been so precious to me. And somebody was going to be feeling these same things about Sam Lodge, probably his wife and certainly his parents, when they learned that he was now broken and forgotten in a closet in a shabby little motel in the middle of a nowhere planet in a nowhere backwash of the dark and rolling cosmos.

I did the only thing I could. I went to the phone and called Chief of Police Jane Avery.

Six days ago, he had to change cells, again. Five times in a year-and-a-half.

Another one of the warden’s grand plans. Probably got the idea from one of his Sociology texts.

He did what he always did, put his toothbrush and toothpaste and shampoo and hairbrush and deodorant and shaving cream and razor into his gym bag and shambled in line behind a guard who led him to a new cellblock.

Guy in the cell is this big dumb shaggy hick with warts or something all over his face.

Guard locks him in.

First thing he does, he starts sniffing the air.

What in hell is that smell?

So dirty, so overwhelming he feels like he’s choking.

“Name’s Lumir.”

He nods to Lumir.

“Not as loud over here in this cellblock. Not as many jigs.”

But he’s still sniffing, trying to figure it out.

“You don’t mind, I like the top bunk.”

“You cut your stools with water, Lumir?”

“Huh?”

Читать дальше