“There was a lot of blood.”

“Yeah?” he said, all frayed red bow-tie and frayed polyester white shirt and frayed ancient blue cardigan. “A lot, huh?”

“Cut her throat.”

“God damn.”

“And she was a looker, too.”

“Young, huh?”

“Young enough.”

“God damn,” he said to my back after I’d nodded good night and was starting out the door. “Sure wish the Chicago papers was going to cover this.”

The screen door slammed behind me.

The old fart said, “Hey.”

I stopped, turned around.

“You got a phone call.”

“From whom?”

“Guy named Tolliver. Is that the rich Des Moines Tolliver?”

“He leave a number?”

“Said you had it.”

“Thanks.”

“Is that the rich Des Moines Tolliver?”

“I’m not sure.”

He looked disappointed.

In my room, I locked up for the night, opened a Pepsi, sat down on the edge of the bed, lifted the receiver, dialed a long-distance operator and dialed Tolliver. My room was shadowy and chilly, a tomb of secrets, furtive adultery, broken dreams and bright doomed hopes.

The maid answered. I had the impression she didn’t care for me awfully much. Maybe she knew I was a hypocrite about tabloids.

“I’ll see if he’s taking calls,” she said frostily and set the phone down.

“Hello,” said a deep voice that sounded both intelligent and curiously humble. I guess I’d been expecting the stereotype robber baron to answer.

“Mr. Tolliver?”

“Yes.”

“My name’s Jim Hokanson.”

“Yes, Mr. Hokanson, that’s what Katie said. Katie, my maid.”

“Well, I called you earlier tonight before it happened.”

“Before what happened?”

“Before—” I stopped myself. “Have you heard from the police tonight, Mr. Tolliver?”

“The police?”

“Yes. There’s been — some trouble.”

“What kind of trouble?”

God, now I’d have to tell him.

“Mr. Tolliver, I wish I didn’t have to tell you this but — your daughter Nora’s been murdered.”

A long enigmatic silence. “My daughter Nora?”

“Yes.”

“Has been murdered?”

“Yes.”

“And you are who, exactly?”

“Jim Hokanson.”

“Are you a police officer?”

“No.”

“Are you a private investigator, then?”

“Something like that.”

“I see.” A pause. “Mr. Hokanson?”

“Yes.”

“Mr. Hokanson, this is going to come as a shock to you, but I don’t have a daughter.”

“I met her.”

“You met someone who perhaps told you she was my daughter, but she wasn’t.”

“I feel pretty goddamned foolish right now.”

“As well you should, Mr. Hokanson. As well you should. Now give me your exact location. I have a plane of my own, and I’m going to fly over there tomorrow.”

“I’m really sorry about this.”

“Quit babbling, Mr. Hokanson, and tell me where you’re calling from. I want to find out just what is going on.”

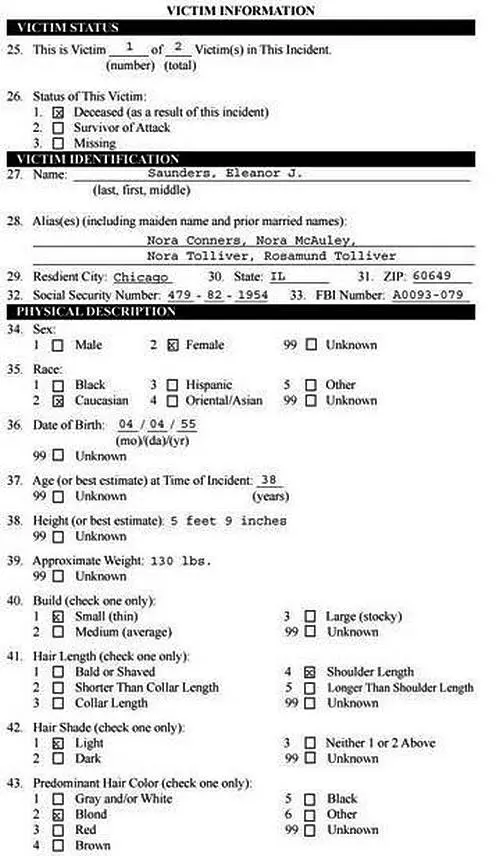

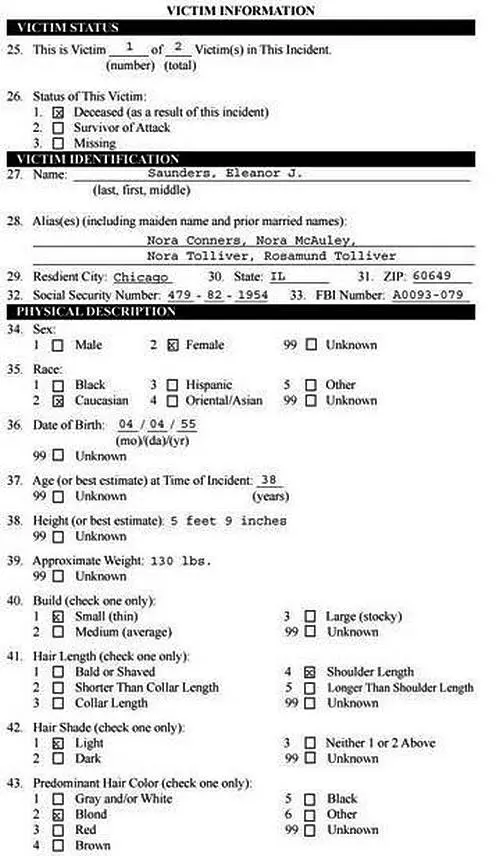

This is the page that Jane Avery — make that Chief of Police Jane Avery — pushed in front of me while I was eating breakfast in a sunny booth in Fitzwilly’s Cafe the next morning. She wore a crisply laundered new blue police shirt and dark blue pants with knife-sharp creases. In the sunlight, her freckles were more vivid than ever, and her tiny nose and white, white teeth more fetching than ever.

“Does any of this sound familiar?”

“I haven’t swallowed my waffle yet.”

“I’m not kidding, Jim.”

“Neither am I. I’ve got a mouthful of food.”

“So swallow.”

I swallowed.

“First of all,” I said, “this is a form that relates to sexual homicide.”

“After she was killed, she was raped.”

“God,” I said, trying not to think of the odd vulnerability that had always rested in Nora’s eyes.

I looked over the form some more. “Eleanor Saunders. Chicago. Age thirty-eight.”

“And her companion’s name was Karl Givens.”

I just looked at her. Didn’t say anything.

“Maybe you knew her under some other name.”

“Who said I knew her?”

“I watched you look at that blue Cadillac last night, when they were bringing the Saunders woman out. You knew her, all right.”

A waitress came. Jane ordered coffee, black. It was nice in here, mote-tumbled sunlight streaming through the front window, an early 1960s Seeburg jukebox standing in the comer, with maybe even a few Fats Domino songs on it, and mostly quiet people in work clothes who knew and seemed to like each other. A place like this in the city, at 8:12 A.M., would have been a madhouse.

“You going to tell me about her, Jim?”

“Didn’t know her.”

“Look at me and tell me you didn’t know her.”

I raised my eyes from the last of my waffle. “Didn’t know her.”

“You’re lying.”

“I didn’t know that you called visitors liars.”

“You do if you’re chief of police. And if your guest happens to be lying.”

The waitress came back with her coffee. “Thanks, Myrna,” Jane said.

She sipped her coffee.

“You going to invite me over for dinner tonight?”

“I don’t know yet, Jim. You really make me mad.”

I’d put our remarks down to normal man-woman banter until just now. She really was angry, but she was so quiet about it, I hadn’t been able to tell until she’d told me.

“I’m sorry.”

“Then you’re really not going to tell me how it is that you and the dead woman came to town on the same day, at the same time, and how she got herself murdered and how you claim not to have known her?”

“How do you know we arrived the same day at the same time?”

“I checked. That’s my job.”

“I wish you’d calm down.”

“I wish you’d tell me the truth.”

“How about the man with her?” I’d almost called him Vic.

“What about him?”

“Is he still alive?”

“Not for much longer. If he doesn’t improve by noon, they’re going to put him on a helicopter and take him to Iowa City. But even that probably won’t do much good.”

“I really do wish you’d invite me over tonight.”

She stood up and clattered a quarter on the table. “I really do wish you’d tell me the truth.”

She left.

In the car, I spent twenty minutes going through Peary’s profile. Here we had three suspects:

Cal Roberts

Richard McNally

Samuel Lodge

According to Peary’s profile, and he’d been just about the most skilled profiler I’d ever worked with, these were our man’s personality characteristics:

Above-average intelligence

Socially competent

Sexually competent

Demands submissive victims

At some point, I’d probably send the FBI Behavioral Science Unit all the material that Peary had gathered.

These days, the FBI is inundated with so many requests for help from local police departments that there’s now a long waiting line. The budget doesn’t allow for the FBI to accept every case, so the trickiest ones tend to get taken first.

This is where I can help small-town police departments. Because I’m a former employee, I know whom to call and what kind of specific help to ask for. I can usually speed things up. Then, when the FBI returns its assessment of the material, I can show the local police how to implement it into their investigation.

Which is just what I was trying to do as I sat there — to think of the three suspects in light of Peary’s eight-page profile.

Читать дальше