‘You went into the water to find the package? Why?’

‘For you, it was for you.’

He heard a growl of laughter, then it was translated and the Englishman too, laughed.

‘For me? Incredible… Perhaps because you knew who I used to be. Get your clothes off. Dry yourself.’

Hamid stood beside the car, hopped from foot to foot, stripped himself bare, and the cold lathered his skin. He rubbed hard with the towel and brought sensations of heat and chill to his body. He put his clothes into the plastic bag that had held the package.

‘Will it still work, after that time in the water?’

He sat on the back seat and the heater was turned high. The doors were slammed. The fisherman and his son stood on the end of the pontoon, did not wave but gazed impassively into the headlights.

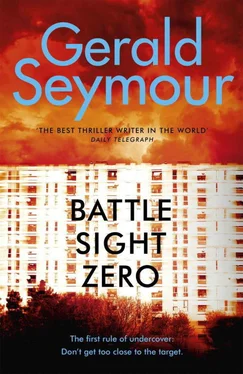

Through chattering teeth, Hamid answered. ‘It will work, as normal. It is an assault rifle. I can feel it, the shape of it, distinctive. It will work as well as the day it was made because it is a Kalashnikov.’

He was so thin she thought she could have snapped him in half. It did not matter how much Karym ate, he never put on weight. His sister was always fussing about her clothes size, sometimes near to tears. At first her hands had not explored him. Because of the way he rode the old scooter, hardly clear of the Saint Charles railway station, and going west, she did. Prompted by him. At first she had tried to sit upright and hold on to the bar at the back of the pillion seat, and she had shrieked twice, once when he swerved past a slow vehicle and the other when he had hit a pothole. Her arms now were around his waist, her fists clenched over the button on his stomach. She held him tight.

Hot breath on the nape of his neck. A strange smell on her body which he did not recognise. No helmet, and he thought her hair would have careered out behind her. The scooter was not a Ducati 821 Monster, did not have the thrust of 112 horsepower: it chugged at up to 65 kilometres an hour, throttle full… The girls on the project, up until the time of his new fame, would not have considered riding behind him, enduring the hard seat, going at such pathetic speed. He had been surprised that she had said she would come with him, fancied it a delusion of excitement. He thought she was naked beneath her T-shirt. He gave her a hard ride and her hold over his stomach was tight.

Zeinab saw the bright lights ahead.

It had been a moment of madness – the second in one evening. Sleeping – for part of the night – with the driver, her dupe boy, was one. Allowing herself the stupidity of swinging a leg over the seat of the kid’s scooter was the second… And she was exhilarated, allowed the pleasure to ripple in her. Half-dressed, she was caught by the wind that seemed to scour her body, liberated.

Did not need to have gone to bed with Andy Knight. Did not need to have gone into the deserted streets of Marseille on the back of a pathetic underpowered scooter and did not need to have clung to his waist… a madness and a freedom. His English was hesitant, accented, but understandable. He twisted his head, with his eyes off the road, shouted at her that the lights were where he lived, and gunned the engine and coaxed minimally more speed from it. They came to a wide entrance that seemed to be defended by heavy stones. Youths came forward.

There were parts of Manchester where she would have been advised not to be when the light fell. She thought this one an equal. Most of the youths wore balaclava masks, or had scarves tied over their faces. She dug her fingernails into the boy’s stomach, felt the scrawny flesh below his shirt. She had not known freedom before. Could have called out into the night, at the sporadic street-lights and high blocks, ‘Why not?’ All of her life, school in Dewsbury, carted to the mosque, disciplined at home – at the university, and under the strictures of academic work and timetables for producing essays and passing exams – with the little group and struggling to be accepted past the prejudice wall of Krait and Scorpion – never free. She held the stomach of the boy, felt feeble muscles cramped in knots. He shouted at the youths, and they backed off, as if disappointed that he had brought home a girl.

He parked. She lifted her leg, swung it over the pillion. Wind blasted her face, her chest and thighs. She was eyed, a stranger, as would any man, or woman, brought late at night into Savile Town. He took her hand. She was older than him, taller than him, stronger than him: he held her hand and she allowed it. He led her up a dried mud path and they passed shrubs, and their shadows were thrown, and a hundred televisions seemed to blast them, then a pool of darkness and then the hallway of a block. She smelt faeces and urine and decayed food. A queue stood here. A man came from a doorway, clutching fifteen or twenty kilos of merchandise, wrapped in newspaper and wedged into a hessian shopping bag. Two kids stood at the doorway – the door was ajar, a voice sounded from inside, and one of them waved forward the man next in line – and each had his face covered and each carried a gun. Both had slender bodies, would have been younger than the boy who had brought her… all part of a liberation, the new-found freedom.

He said the elevator did not work. They climbed together. Too many stairs and she had started to pant. He held her hand, helped her. She smelt cooking, she heard arguments, vivid laughter, her breath wheezed. Up three flights, and came to a landing. No paint on the walls, but graffiti in Arabic, different to what she knew of the symbols used in Quetta, in Pakistan, and her hand was freed, and a key was produced, and a door unfastened, and her hand taken again.

A girl sat on a sofa, had washed her hair and had a towel round her head. Had an empty plate beside her, held a can of juice. The TV showed a singer. The boy nodded to her, and she shrugged. What did it matter to her if he came home with a girl? Zeinab supposed she was regarded as a symbol of success, an object to be displayed. She was led across the room and he pushed a door open. His bedroom was lit by a small lamp beside the bed. The bed was unmade. Clothes, unwashed, crumpled, covered half the floor. A TV was on the wall. A poster of a singer, female, a view of a cliff edge in mountains with a village tucked under the escarpment. In a cheap frame was a photo of a middle-aged man and a woman, probably his mother and father. The image that dominated, stopped her dead: an AK-47 rifle… she stared hard at it, then looked around and fastened on the bookcase. She read the titles of the books on the top shelf… AK-47 Assault Rifle, the Real weapon of Mass Destruction and The Gun, the AK-47 and the Evolution of War and AK-47 The Story of a Gun and The Gun that Changed the World … The boy had a library, more than 50 volumes and most of them hard-backed and therefore expensive, and lived in a foul tower block that would be raddled with addicts and drug customers, and all he read was about the gun that she had been recruited to courier back to the UK… Everything else in the room was disgusting, dirty, nothing was treated with pride except for the book shelves and their contents. And, she should not have come, and she reckoned she would be late returning, and the boy spoke.

‘You are looking at them?’

‘Should I call you an expert, on the Kalashnikov?’

‘Almost, perhaps… I read about it, I hope one day to have one. My confession, I have never fired one. My brother will not let me even hold one. He says that only boys ready to die, wanting Paradise, have a Kalashnikov. I can strip one, can clean one, can…’

‘Why is it so special?’

‘You want to know? Have you not come to purchase a supply route for hashish? It is narcotics that you want?’

Читать дальше