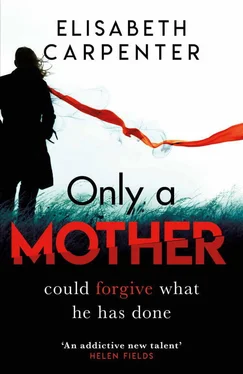

I keep trying to pinpoint the time when things went so wrong; I keep thinking about how he used to be, when he was so pure, innocent. Like when he was only three years old, covers up to his chin, in this very bed I’m sitting on.

‘I don’t want to leave home when I’m a man, Mummy,’ he said. ‘Can I marry you?’

‘I’m afraid not, love. But you don’t have to leave if you don’t want to.’

Then he burst into tears.

‘What’s wrong, love?’ I said, my heart melting and breaking at the same time.

‘I never want to be a daddy. I saw Mark’s dad at playschool and he told Mark off because he spilt juice down his front.’

‘But mummies tell kids off too.’

‘But… but…’ He wiped his face with his covers. ‘You don’t shout as loud as he did. And if I was a daddy, I’d have to meet another mummy and I just want you .’ He started crying again.

I realise that I’m crying too, now.

I go to the window and there’s no sign of my son outside. If I looked everywhere, there would be no sign of the little boy that once cried himself to sleep because he loved me too much. That boy is long gone.

I’d half hoped that by snooping, reading these letters, it would’ve jinxed Craig into coming home. When I used to smoke and lit one waiting for a bus, it always used to come. But, no. No sign.

I carefully put the letters back and go downstairs.

I get my phone from my handbag and select Craig’s number.

‘Craig? It’s me, your mum. Are you there?’

Sounds like static coming down the line, then a strange sound as though a car is going under a series of tunnels .

‘Craig!’ I shout louder; he might have answered it by mistake in his pocket or something. ‘Can you hear me?’

I press my mobile to my head, so it squashes my ear flat.

Faint music. A car radio maybe.

‘Craig!’

There’s a noise like someone’s throwing the phone against a hard surface. ‘Shit!’ A man’s voice – it doesn’t sound like Craig. And then the phone goes dead.

My heart’s pounding. What if someone’s out for revenge? What if Brian’s kidnapped him to punish Craig for taking Lucy away from him? Or it could be Jenna’s dad, angry that he hasn’t seen justice for his girl.

I open the front door and walk out onto the pavement, looking left and right. It’s quieter than it normally is, but there’s a car parked at the top of the street; two people in the front seats with their heads down. It’s not a new car. Craig used to tell me that drug dealers always had flash cars, so they can’t be dodgy. But surely the police would have nice cars too. If Craig was in trouble, they wouldn’t be just sitting in the car like that, they’d be straight through my door.

I go back inside and pace the living room.

I could call the police, but it would sound silly: my son didn’t answer his phone properly. I haven’t seen him for almost two days; his supervising officer didn’t mention anything like this – or I wasn’t listening properly, there was too much to take in. Leaflets. They gave me some leaflets. I search the kitchen drawers and I can’t find them.

No, no. I can’t call anyone. I don’t want to get him into trouble if he was doing nothing. Though if he’s with Jason, then I doubt they’re doing nothing.

The world seems to have gone quiet. No voices on the street, or jazz music from next door. I’m sure I can hear the ticking of the grandmother clock in the dining room. These four walls feel like they’re closing in, laughing at me. It was better when I knew where he was, that he was safe. It’s a terrible thing to think, but I’ve felt so unsettled these past six days – even compared to the days and nights the house was targeted. The police were no use then either.

I go to the kitchen and splash my face with cold water.

When that first lit newspaper came through the door, I was fast asleep on the sofa when the smoke alarm went. I dialled 999 after putting it out myself with the water from the kettle. I know they say not to do that, that you have to get out and stay out, but it was only small. It was more of a smoulder than a fire. Whoever put it through my letterbox obviously hadn’t put enough petrol or whatever they used on it. It would’ve done more damage had I left it. ‘Get a landline put in upstairs,’ the fireman said, five minutes after I called. ‘It’s lucky you’ve wooden floors and no curtain behind the door… curtains plus a carpet would’ve gone up like that.’ He’d made a whooshing sound while sweeping his arm through the air.

I splash my face with water again.

Jason. I need to contact Jason.

But that would mean asking Denise for his phone number.

I grasp the edges of the kitchen counter and look to the calendar. I’ve underlined the nineteenth of February. I don’t know why I always do that – it’s not as if I’d forget. Thirty-nine years this year since my mother died. Where does it go?

Last Monday is circled in blue ink and I even wrote a little exclamation mark and a smiley face. It’s been seven days today since Craig was released. What planet was I on then when I drew that – what did I think it would be like? I shouldn’t have lied to Adam last night on the phone. It can’t be like it was back then. If he’s in trouble then they’ll have got to him by now, but he’s out there somewhere and he might be hurt.

I walk back into the hallway and open my address book. I kept that reporter’s card; I knew I had. I could tell him all about my son and how it couldn’t possibly have been Craig and now he’s in trouble. I’ll let him know that I’m still searching for a man called Pete Lawton who was with Craig when Lucy was murdered. I keep checking, but there’s been no reply from the one who opened my message on Facebook. It’s like I’m chasing a ghost, someone who doesn’t exist.

I hold the card as I walk into the living room. I grab the remote and switch the television on to have a comforting sound in the background. I don’t want to hear my voice echoing in this house.

The local news is on. Before I press the button to change the channel a familiar face is staring back at me. The photograph fills the screen. A pretty, young girl in a school uniform: Leanne.

Luke

Following his talk with Rebecca Savage this morning, Luke is now convinced that Erica Wright has been covering up for her son regarding Jenna Threlfall’s murder. But why would the police believe an alibi from a relative if it weren’t true? Perhaps it’s because the murders seemed to differ.

Several aspects of the police investigation have remained under embargo: pieces of evidence that couldn’t be made public but were leaked to a member of his office.

There were key areas in which Lucy and Jenna’s cases were different. Lucy was found hidden, crudely and amateurishly, in woodland. There was a rudimentary covering of leaves, earth and sticks that were perhaps pawed away by the dog that found her. Her clothes were on her person and there was nothing missing from the body. Jenna, on the other hand, was found in a place one couldn’t miss – she’d obviously been moved post-mortem and her skin had been crudely wiped with bleach, presumably to rid the body of foreign DNA. While Luke believed that the treatment of Jenna’s body could be perceived as different, it still seemed naive to use household bleach.

Luke types the names of Jenna’s parents, Sandra and Philip Threlfall, into Google. There are hardly any results and those he finds are mentions in parish newsletters or results of cricket matches. Nothing of importance. He doubts his own parents would appear in any Google searches either.

He reads through the old interviews. Jenna Threlfall had a sister, Olivia, who was thirteen years old at the time – not that they’d been able to print any details about her then.

Читать дальше