Someday, she thought. Someday, cat, you’ll respect me.

It was a ridiculous thought, but it buoyed her, nonetheless. She turned back to the wheel, ducked her head out the portside window, and surveyed the dock, where Jason and Al Parent stood ready to loosen the mooring lines.

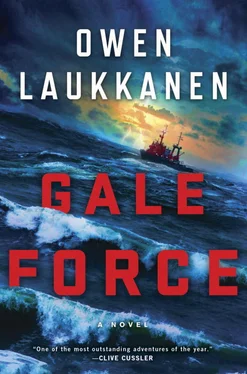

The main engines were warmed. The crew was aboard. The Gale Force was as ready as she was going to get. McKenna nodded to the men. “Cut her loose, fellas,” she told the Parents. “Let’s go catch us a Lion .”

The American Coast Guard brought Hiroki Okura and the rest of the Pacific Lion ’s crew to Dutch Harbor—eventually.

First, the airmen flew Okura to the cutter Munro , where he rejoined the Lion ’s crew in a helicopter hangar at the stern of the ship. The Coast Guard seamen brought the crew blankets, hot coffee, and soup, and the sailors from the Lion eyed Okura warily. They’d heard how he’d fought to remain on the ship.

The first Coast Guard airmen had flown back to Dutch Harbor. Now, in daylight, the Munro sent its own helicopter, a bright orange Eurocopter HH-65 Dolphin, to survey the ship. The Munro’s crew had opened the hangar doors, and the Lion ’s survivors wandered out to watch.

Morning had broken, sunny and brisk, a beautiful day, the sea as close to flat-calm as Okura had ever seen in this part of the North Pacific. In the distance, three hundred yards off the starboard quarter, the Pacific Lion languished.

If only I’d had more time.

The crew of the Dolphin helicopter boarded the Lion and stayed there for about an hour. Okura smoked cigarettes on the Munro ’s afterdeck and watched, until the Dolphin’s crew was winched back up to their helicopter and flying to the cutter. He did not see any sign that the crew had found Tomio Ishimaru.

Within five minutes, the Dolphin had touched down on the deck of the Munro. The pilot and his crew climbed down and hurried across the landing pad, conversing briefly with the Lion ’s captain, before disappearing inside the ship.

The captain gathered his officers. “The ship is still very unstable,” he told the men. “The Coast Guard expects it will sink. There is no chance of retrieving our belongings.”

“So what are we supposed to do?” Okura wondered.

“They are sending us home to Japan,” the captain replied. He looked at Okura, and his eyes narrowed. “I expect the company will want to know why the ballast transfer failed, Okura—and why you behaved so erratically after the disaster.”

• • •

A DAY LATER, Okura surveyed the small town of Dutch Harbor as he descended the Munro ’s gangplank to the government dock. The town was pretty, that was for certain, a ramshackle crescent of houses and small buildings hugging the harbor bay, surrounded by lush mountains. The air was crisp and bracing and, here and there, the sun shined through the clouds. It was a beautiful day.

On the dock, a school bus was waiting to take the Lion ’s crew to the town’s community center, where they would stay until a plane could take them home.

“Welcome to Alaska,” a customs official told the crew as they found their seats on the bus. “Your plane should arrive sometime this afternoon. Until then, we’ll make you as comfortable as we can.”

The chief engineer, a chubby man in overalls, raised his hand. He’d been on his way up from the engine room when the Lion had capsized. “We have no clothes,” he said.

The customs official nodded. “We’re going to try to scrounge up clothing for you. Everything we can provide, we will.”

“Food?”

“Yes, definitely. We have volunteers cooking you a meal as we speak.”

“Will we be allowed to go for a walk?” someone else wanted to know. One of the deckhands, a reputed alcoholic. Okura suspected he knew where the man wanted to go.

“No walks,” the official said. “As of right now, you’re not officially admitted into the United States. We’re just giving you a place to stay until you can go home.”

“What if we have our passports?”

The bus was moving now, rumbling across the dock toward a stretch of gravel road. The customs officer lost his balance and hit his head on the ceiling. Winced.

“We’ll deal with that on a case-by-case basis,” he said. “If you have any more questions, come and see me when we get there.”

The officer sat down, rubbing his head. Some other crew members shouted questions in halting English. Okura turned to stare out the window. If I had my passport, I wouldn’t need to go back to Japan.

But he didn’t have his passport. It was locked in the safe in his stateroom on the Pacific Lion , two hundred and fifty nautical miles to the southwest. And anyway, where would he go? What would he do?

If I had my passport, and fifty million dollars. Then I would be set.

But he had neither, and he sat and brooded in silence as the bus lurched and jostled its way into town.

SEATTLE

McKenna guided the Gale Force out of its berth and into Lake Union, past rows of fishing boats, pleasure craft, and tugs to the George Washington Memorial Bridge, where the water narrowed northwest into the Fremont Cut, splitting north Seattle in two. The ship canal was narrow and crowded with traffic, and McKenna piloted the tug carefully as she approached the system of locks at Salmon Bay that would drop the Gale Force twenty feet to the Puget Sound.

It was never the most relaxing way to start a journey, but McKenna felt calm anyway as the tug waited its turn and descended through the locks, ducked under the train bridge, and turned north into Shilshole Bay, leaving Seattle behind for the open water of the sound. She was happy, at least, to have escaped the city. The water was where she belonged.

There were problems to consider, of course, and all of them pressing. There was the problem of money; namely, that the Gale Force didn’t have much. There was the issue of the Pacific Lion ’s pronounced list—the Coast Guard was reporting sixty degrees—and how McKenna would reverse it without the whiz kid in the picture.

She’d called around, tried every naval architect she could think of, some of them salvage experts with whom her dad had worked before Court Harrington, others she knew only by reputation. The response had been singularly depressing.

“No offense, but I just don’t know you, Ms. Rhodes,” a professor at the Webb Institute told McKenna. “I’m sure you’re just as good as your father at this stuff, but if you’re asking me to fly across the country to work with an unknown entity, I’m going to need at least a hundred thousand dollars up front.”

“I can’t offer you that much,” McKenna replied, “but I can assure you a share of the profits. We stand to make—”

“I know what you could make,” the professor interrupted. “I also know you could very well walk away with nothing. And I just can’t take that risk. Not with an unproven captain.”

The story didn’t change much, no matter who McKenna called. Nobody knew her, except as Riptide Rhodes’s little girl. No one trusted her ability to bring the Lion to safety.

• • •

BEYOND THE ARCHITECT CONUNDRUM, there was always the possibility, too, that the ship would sink before the Gale Force arrived, or that some other salvage outfit would put a line on her first. By rights, McKenna knew she should be pulling out her hair right now, or turning the tug back toward the dock and looking for a nice job in an office or something, but instead, she felt calm. Serene. She felt her dad here, somehow.

Читать дальше

![Маргарет Оуэн - Спасти Феникса [litres]](/books/405290/margaret-ouen-spasti-feniksa-litres-thumb.webp)

![Оуэн Дэмпси - Белая роза, Черный лес [litres]](/books/412437/ouen-dempsi-belaya-roza-chernyj-les-litres-thumb.webp)