To my father, John Heller, the best storyteller I ever heard.

Who first took me out in small boats, and who sang “Little Joe the Wrangler” and “Barbara Allen.”

They had been smelling smoke for two days.

At first they thought it was another campfire and that surprised them because they had not heard the engine of a plane and they had been traveling the string of long lakes for days and had not seen sign of another person or even the distant movement of another canoe. The only tracks in the mud of the portages were wolf and moose, otter, bear.

The winds were west and north and they were moving north so if it was another party they were ahead of them. It perplexed them because they were smelling smoke not only in early morning and at night, but would catch themselves at odd hours lifting their noses like coyotes, nostrils flaring.

And then one evening they pulled up on a wooded island and they made camp and fried a meal of lake trout on a driftwood fire and watched the sun sink into the spruce on the far shore. Late August, a clear night becoming cold. There was no aurora borealis, just the dense sparks of the stars blown from their own ancient fire. They climbed the hill. They did not need a headlamp as they were used to moving in the dark. Sometimes if they were feeling strong they paddled half the night. They loved how the darkness amplified the sounds—the gulp of the dipping paddles, the knock of the wood shaft against the gunwale. The long desolate cry of a loon. The loons especially. How they hollowed out the night with longing.

Tonight there was no loon and almost no wind and they went up through tamarack and hemlock and a few large birch trees whose pale bark fluoresced. At the top of the knoll they followed a game trail to a ledge of broken rock as if they weren’t the first who had sought the view. And they saw it. They looked northwest. At first they thought it was the sun, but it was far too late for any lingering sunset and there were no cities in that direction for a thousand miles. In the farthest distance, over the trees, was an orange glow. It lay on the horizon like the light from banked embers and it fluttered barely so they wondered if it was their eyes and they knew it was a fire.

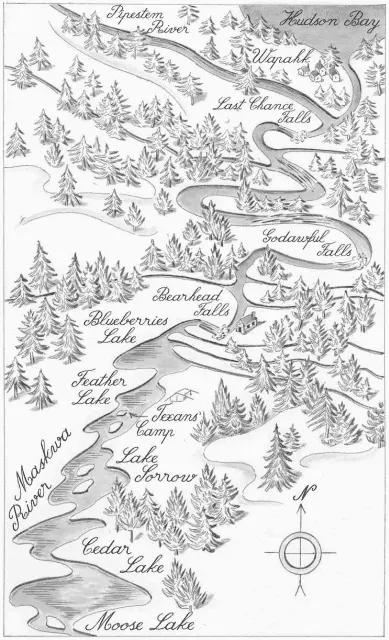

A forest fire, who knew how far off or how big, but bigger than any they could imagine. It seemed to spread over two quadrants and they didn’t say a word but the silence of it and the way it seemed to breathe scared them to the bone. The prevailing wind would push the blaze right to them. At the pace they were going they were at least two weeks from the Cree village of Wapahk and Hudson Bay. When the most northerly lake spilled into the river they would pick up speed but there was no way to shorten the miles.

—

On the morning after seeing the fire they did spot another camp. It was on the northeastern verge of a wooded island and they swung out to it and were surprised that no one was breaking down the large wall tent. No one was going anywhere. There was an old white-painted square-stern woodstrip canoe on the gravel with a trolling motor clamped to the transom and two men in folding lawn chairs, legs sprawled straight. Jack and Wynn beached and hailed them and the men lifted their arms. They had a plastic fifth of Ancient Age bourbon on the stones between the chairs. The heavier one wore a flannel shirt and square steel-rimmed tinted glasses, the skinny one a Texans cap. Two spinning rods and a Winchester Model 70 bolt-action rifle leaned against a pine.

Jack said, “You-all see the fire?”

The skinny one said, “You-all see any pussy?” The men burst out laughing. They were drunk. Jack felt disgust, but being drunk on a summer morning didn’t deserve a death sentence.

Jack said, “There’s a fire. Big-ass fire to the northwest. What you’ve been smelling the last few days.”

Wynn said, “You guys have a satellite phone?”

That set them off again. When they were finished laughing, the heavy one said, “You two need to chillax. Whyn’t you pull up a chair.” There were no extra chairs. He lifted the bourbon by the neck between two fingers and rocked it toward them. Jack held up a hand and the man shrugged and brought the fifth up, watching its progress intently as though he was operating a crane. He drank. The lake was a narrow reach and if the fire overran the western shore this island would not keep the men safe.

“How’ve you been making the portages?” Jack said. He meant the carries between the lakes. There were five lakes, stringing south to north. Some of the lakes were linked by channels of navigable river, others by muddy trails that necessitated unloading everything and carrying. The last lake flowed into the river. It was a big river that meandered generally north a hundred and fifty miles to the Cree village and the bay. Jack was not impressed with the men’s fitness level.

“We got the wheely thing,” the skinny man said. He made a sweeping gesture at the camp.

“We got just about everything,” the fat man said.

“Except pussy.” The two let out another gust of laughter.

Jack said, “The fire’s upwind. There. We figure maybe thirty miles off. It’s a killer.”

The fat man brought them into focus. His face turned serious. “We got it covered,” he said. “Do you? It’s all copacetic here. Whyn’t you have a drink?” He gestured at Wynn. “You, the big one—what’s your name?”

“Wynn.”

“He’s the mean one, huh?” The fat man cocked his head at Jack. “What’s his name? Go Home? Win or Go Home. Ha!”

Wynn didn’t know what to say. Jack looked at them. He said, “Well, you might get to high ground and take a look thataway one evening.” He pointed across the lake. He didn’t think either of them would climb a hill or a tree. He waved, wished them luck without conviction, and he and Wynn got in their canoe and left.

—

On the third day after seeing the fire they were paddling the east shore of a lake called Blueberries. What it said on the map, and it was an odd name and no way to make it sound right. Blueberries Lake. They were paddling close to shore because the wind was up and straight out of the west and rocking them badly. It was a strange morning: a hard frost early that lingered and then the wind rose up and the black waves piled into them nearly broadside, rank on rank. The tops of the whitecaps blew into the sides of their faces and the waves lapped over the port gunwale so that they decided to surf into a cobble beach and they snapped on the spray deck that covered the open canoe. But there was fog, too. The wind tore into a dense mist and did not blow it away. Neither of them had ever seen anything like it.

They were paddling close to shore and they heard shouting. At first they thought it was birds or wolves. They didn’t know what. As with the fire, they could not at first countenance the cause. Human voices were the last thing they expected but that’s what it was. A man shouting and a woman’s remonstration, high and angry. The cries shredded in the wind. Wynn half turned in the bow and pointed with his paddle, but only for a second as they needed speed for headway or they would capsize. His gesture was a question: Should we stop?

An hour before, when they had beached to put on the spray skirt, they had landed hard. Wynn was heavier and having his weight in front had helped in the wind, but then they had surfed a wave into shore and thwomped onto the rocks, which thankfully were smooth; if the beach had been limestone shale they would have broken the boat. It was a dangerous maneuver.

Читать дальше