At Kufra, disguise was nonsense entertained only in fiction. In real life, it was better to teach annihilation and survival. He knew that to appear absolutely authentic, he should be wearing unshorn earlocks and a beard. But he’d have felt ridiculous applying crepe hair, and he’d reasoned — correctly, it now seemed — that the familiar costume alone would confirm his identity. People rarely saw beyond the uniform. Moreover, he carried himself with an air of solemn religiosity premised on an inner belief that he was, in fact, an Orthodox Jew on a rainy day’s outing. Smiling thinly in his beard — the beard he believed he was wearing, although it did not in actuality adorn his face — he thought, To me I’m an Orthodox Jew, and to you I’m an Orthodox Jew — but to an Orthodox Jew am I an Orthodox Jew? There were no Orthodox Jews on the ferry today.

He stepped off the boat at five minutes to four. Again, none of the rangers on the dock asked him to open his bag. His good old friend Alvin Rhodes was not among them. Like a rabbi davening in prayer, he muttered his way past them. At five o’clock, he went into the restaurant and bought three hamburgers, a can of Diet Coke, a container of orange juice, and a hard roll. He sat at a table to eat the hamburgers and drink the Coke. He put the orange juice and the hard roll into the camera bag, in the compartment alongside the pistol.

At a quarter past five, the announcements started, telling visitors to the island that the last boat back would leave in half an hour.

He went into the base of the statue, and up to the men’s room on the second level.

Two men were at the urinals.

He could see shoes and bunched trouser legs under one of the stall doors.

He went into a free stall, locked the door, and waited. At five-twenty, the man in the stall on the right flushed the toilet, stood up, pulled up his trousers, and left. Sonny heard water running in one of the sinks.

A man’s voice — calling from the doorway, it seemed — yelled, “Last ferry leaving in fifteen minutes!”

A urinal flushed.

Silence.

Sonny took the box of toothpicks out of the camera bag. He grabbed a handful of them and stuffed them into the right-hand pocket of his jacket.

He took the loop of fishing line out of the bag and put it into his left-hand pocket.

He could hear a loudspeaker announcing that the last ferry from the island would leave in ten minutes.

He pulled his feet up onto the toilet seat.

The same man who’d called from the doorway earlier — an attendant, a ranger, whoever the hell — now came into the room and shouted, “Last ferry’s about to go. Anybody in here?”

Sonny did not dare breathe.

“Last call for the ferry,” the man said.

There was a long silence.

He heard the man grunt, and visualized him crouching to look under the stalls. Another grunt as he rose. Then his voice coming from the corridor outside, “Last call for the ferry,” retreating down the hallway, “last call for the ferry, last call...”

And then silence.

Sonny came out of the stall at once.

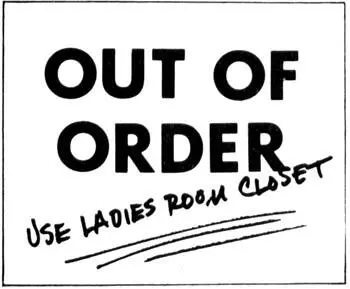

He went to the wooden outer door, painted to look like bronze, and pulled it closed. If he had to, he was prepared to pick the lock on the utility closet door in the alcove — but the door was standing open, just as it had been last Saturday. He took a toothpick from the handful in his pocket, inserted it into the keyway, and snapped it off flush with the face of the lock. There was still room in the keyway’s slit for another one. He slid one in, snapped it off flush, pressed both stubs in solidly with the flat side of a quarter, and then reached into the camera bag at his feet, removing from it the manila envelope bearing the sign Arthur had given him this morning. He took the roll of transparent tape from the bag and began fastening the sign to the door, a sliver of tape at each corner. The sign read:

His hands were trembling.

He was putting the tape back into the bag when he heard footsteps in the corridor. Distant. But approaching. The attendant, the ranger, whoever was coming this way again. He rushed into the closet and took the loop of fishing line from his pocket. Hooking it over and behind the thumb bolt, the only grip on the inside of the door, he was pulling the door toward him when he heard the man’s voice again. Just outside the closed entrance door now.

“Who the fuck?”

Wondering who had closed that outside door.

Sonny tugged on the fishing line.

He heard the outer door opening.

The bag!

He’d left his bag outside the...

He shoved the door open again, reached down for the bag and was stepping back into the closet when the man suddenly appeared in the alcove.

Tall and burly and wearing a ranger uniform.

Blue eyes and a reddish-brown mustache.

His mouth opening in surprise.

“What...?”

But Sonny was already moving forward. As Rhodes reached for the revolver in the holster at his waist, Sonny brought his right arm back, the elbow bent, the hand coming up close to his left cheek. As the gun came free, Sonny released his cocked arm, chopping the hard edge of his hand across the bridge of Rhodes’s nose. He heard the bone shatter, heard Rhodes yelp in startled pain, stepped around him at once, caught the back of his head in a double-handed lock, snapped it sharply forward — and broke his neck.

Rhodes went limp against him.

He dragged him into the closet and eased the door shut again. Tugging on the fishing line as hard as he could, he heard at last the heart-stopping click of the spring bolt snapping into the engaging strike plate. He was sealed inside now. No one could unlock that door from the outside, not with the lock effectively jammed.

He hunkered down beside Rhodes’s body.

Settling his back against the wall, he stretched out his legs and sat back to wait.

It would be a long night.

Geoffrey had brought two flat tins with him, one filled with forty water-soluble crayons, the other with thirty water-soluble pencils, for finer work. He’d confessed at dinner that he no longer had the pencils he’d used to paint on the shiner all those years ago, and had gone to an art supply house the moment he’d left her this afternoon. Now, in her mother’s Park Avenue apartment, he displayed his wares and asked her which eye she wanted done.

“Will it wash off later?” Elita asked.

“Of course,” he said. “They’re water soluble. In four languages.”

Indeed, the printed matter on both tins read water soluble, wasserlöslich, solubles à l’eau , and solubili in acqua .

“Pick an eye,” he said.

“Which do you think?” she asked.

“It’s hard to decide, they’re both so lovely,” he said. “But let’s try the left one. I’m right-handed, so it’ll be easier to work on that side of the face.”

“Are you sure it’ll wash off?”

“Positive.”

“You won’t get any on my blouse, will you?”

“No, no.”

“I hope not.”

She was wearing a white long-sleeved silk blouse she’d bought at Bendel’s. The last thing she wanted...

“I’ll need a glass of water,” he said.

“What for?”

“To dip them in,” he said, and started for the kitchen. “Actually, this isn’t the proper way to use them, one should also have a brush. But it’ll work this way as well.” He found a glass on the counter drainboard, called, “Okay to use this?” and filled it with water. When he came back into the living room, Elita was studying the array of crayons in the larger tin.

Читать дальше