I urge you, therefore, to confer at your soonest convenience with Messrs Regan and Weinberger, Vice Admiral Poindexter, Colonel North, and the Joint Chiefs of Staff to implement at once a plan for immediate military action.

My kindest regards,

George Bush

“Has the signature been checked?” Alex asked.

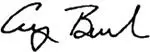

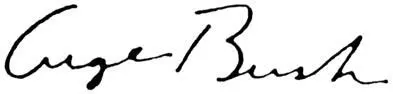

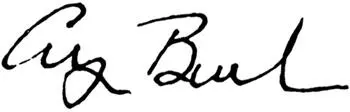

“It’s a good forgery, but not good enough. Here’s the President’s real signature — from letters he wrote back in 1986,” Peggot said, and put the sample on Alex’s desk:

“But the signature on the letter more closely resembles this ,” Peggot said, and produced another document:

“This is the President’s current signature. Signatures change over the years, you know...”

“Yes, I know,” Alex said drily.

“What I’m saying,” Peggot said, “is that the signature on this letter was obviously premised on the President’s current signature. The letter could not possibly have been written in April of 1986, as it purports to have been.”

Purports, Alex thought. A typical Peggot word.

“How about the stationery?” he asked.

“Well, this is a copy of the letter, of course,” Templeton said, puffing on his pipe and stinking up Alex’s entire office. “But vice-presidential stationery would be relatively easy to come by.”

“Anyone worth his salt,” Peggot said, nodding in agreement.

“We’ve tracked the typewriter type,” Templeton said. “The letter was typed on an IBM Selectric. A fair number of them are still shipped to the Middle East, by the way. The typeface is Prestige Pica 72.”

“Are you saying the letter originated somewhere in the Middle East?”

“Possibly.”

“ Very possibly,” Peggot said, and nodded again.

“Where’d it turn up?”

“The letter? You understand we haven’t located the actual typewri...”

“Yes,” Alex said, and refrained from rolling his eyes heavenward. “The letter. Where did it surface?”

“A digger in Tripoli passed it to one of our people.”

“Reliable.”

“Our man?”

“No, the digger.”

“Oh. Yes, so far.”

“Where’d he get it?”

“She. Someone at GID copied it for her.”

“Who?”

“Confidential source. She won’t reveal it.”

“Mm,” Alex said.

The General Investigation Directorate, familiarly called the GID by American and British agents, was once headed jointly by Police Colonel Mohammed Al-Ghazali and a man from Benghazi named Sáed Bin Ūmran, who’d been recently muzzled and put on the shelf. Al-Ghazali reported directly to the Secretariat for External Security, which was formed in 1984 by order of the General People’s Congress, and whose responsibilities included the supervision and coordination of all Libyan intelligence and counterintelligence operations, including those of the GID. There was only one intelligence group controlled directly by Quaddafi, with no intermediaries. The only thing the CIA knew about this elite organization was its name: Scimitar.

“My suggestion is to forget all about the letter,” Peggot said.

“Why?” Alex asked.

“It’s obviously false,” Templeton said, and looked into the bowl of his pipe to see if it was still lit.

“What’s it doing in Libya?” Alex asked.

“What difference does it make?” Peggot said.

“How’d it get there?” Alex said.

“Who cares?” Templeton said. “It’s a forgery.”

Which is exactly the point, Alex thought.

Sonny set the nozzle on the plastic bottle to the STREAM position.

Standing on the beach, he pulled the trigger.

A stream of insecticide shot out some fifteen to twenty feet, exactly as promised on the bottle’s label. To make certain the first shot wasn’t just a freak, he tried it a dozen times. Not once did the stream fall short of the advertised distance. Moreover, he was able to trigger off fifteen shots every five seconds.

He first practiced on the flat because that was what the terrain would be tonight. But if he had to wait till the Fourth, he had to be certain he could hit the President with a deadly stream of poison from above .

In the sand below the upstairs deck of the beach house, he positioned a metal pail some eight feet out from the house. He estimated that the deck was eighteen feet or so above ground level. He climbed the staircase, and took position behind the railing, the bottle of insecticide in his hand. He felt as if he were standing at the counter of a carnival shooting gallery, aiming a water gun at a bull’s-eye that would move a mechanical rabbit uphill. Each time a stream of water hit the bull’s-eye, the rabbit would move up a notch. Whenever one of the rabbits went over the top, a bell would ring, signaling a winner.

No bells went off in the sand today.

But after a handful of test shots, he found he could accurately direct a stream that fell in a shower of smaller droplets into or onto the pail. Nor was it even necessary to hit the exact center of the pail each time; the radius of the falling drops was wide enough to encompass at least some part of it, and that was quite enough.

But he kept practicing.

A little girl walking toward the steps leading over the dune stopped to watch him.

“What’re you doing?” she asked. Five or six years old, he guessed, and fascinated.

“Trying to get this stuff in the pail,” Sonny said, and went right on with his work.

The little girl kept watching.

Different agendas, he thought.

“Why?” she asked at last.

“Oh, just for fun,” Sonny said.

“Can I try?” she asked.

“Nope,” Sonny said.

“Why not?”

“Too dangerous,” he said.

The little girl watched awhile longer and then, bored, climbed the steps and disappeared from sight. Sonny kept practicing, triggering off three shots every second, swinging the bottle in an arc now to cover an even wider radius each time.

If the tiniest bit of sarin fell on the President’s head, it would be absorbed immediately into his scalp. If he brushed at whatever fell onto his hair, it would touch his hand, magnifying his exposure and his vulnerability. Either way, he was a dead man.

There was just one other thing to check.

He dialed the 800 number on the plastic bottle, and got a recorded voice.

“Thank you for calling the Raxon Consumer Research Center. All lines are busy just now. Please hold and our next available representative will help you.”

He waited.

A live voice came on the line. A woman.

“Research Center,” she said, “may I help you?”

“I hope so,” he said. “I have a bottle of your Raxon Multi-Bug Killer...”

“Yes, sir?”

“And I was wondering what the plastic is made of.”

“In the bottle, do you mean?”

“Yes, please.”

“Well... I’m not sure, let me check.”

He waited.

When she came back on the line, she said, “We don’t have a number on that. I can tell you that the EPA doesn’t recommend recycling of the bottle. What’d you want to use it for?”

“It’s such a good spray bottle,” Sonny said, “it would seem to have a lot of uses. I’m just wondering if the plastic would be inert to organic solvents.”

Читать дальше