“... fond de la base jusqu’à la torche est quarante-six virgule cinq mètres. Pour avoir accès à la couronne, il faut monter trois cent cinquante-quatre ...”

The pilot of the ferry headed her straight for marker thirty-one, then brought her around so that she slowly revealed the statue first in profile, then in a three-quarter view, and then dead-on, the folds of her garments cascading to the pedestal in a flow of green copper, the left arm cradling the tablet, the sleeve of the raised right arm falling back, the golden torch in her right hand capturing the rays of the early afternoon sun, the sky behind her a vibrant blue. Viewing the statue as the boat circled her, revealing her as if in separate frames of motion picture film, Elita felt a fierce patriotic pride mixed with a sense of place and history. Sonny felt nothing.

The boat circled the island and came into the dock. In the distance, Elita could see the American flag flying from a tall flagpole. This, too, thrilled her. Sonny was busy looking down at a sign on the dock:

At the

Statue of Liberty

All Packs,

Packages,

Briefcases, etc.

are Subject to

Search

They came down the gangway and onto the dock. A high shed-like structure opened onto a wooden walkway that led to a huge brick-paved circle at the center of which stood the flagpole Elita had seen from the deck of the ferry. A tree-flanked esplanade — similarly paved with brick and ornamented with rectangles outlined in blue tile — led to the rear of the statue, standing tall on her pediment, a seeming halo of light around her crown.

“What happened to you at the train station?” Elita asked. She’d been dying to ask this from the moment he’d called, but had only now found the courage to do so.

“First, I couldn’t find a porter,” he said. “Next, I ran into a guy I went to Princeton with, and he dragged me off to...”

“But I was standing there waiting for...”

“Well, I had your number. I figured you knew I’d call.”

“Then why didn’t you?”

“But I did.”

“It’s been three days.”

“I lost the slip of paper.”

“What slip of paper?”

“The one I wrote the number on.”

“Then why didn’t you look it up in the phone book?”

“I didn’t know your mother’s first name. There are dozens of Randalls in the Manhattan...”

“She uses her maiden name now. It’s...”

“Besides, I finally found the slip of paper.”

“Well, in case you lose it again, her name’s...”

“I’ve already written it in my book.”

A National Park Service ranger wearing olive drab trousers, a tannish-green shirt and a Smokey the Bear hat was waving tourists onto one or another line on either side of the center doors leading into the base. He was a tall, burly man with blue eyes and a reddish-brown mustache, and he kept chanting, “Admission is to the right or left. No admission through the center doors. Admission is to the right or left, depending where you want to go.”

“Excuse me,” Sonny said.

“Yeah?” the ranger said, and then immediately to the approaching crowd, “Admission is to the right or left, depending where you want to go. No admission through the center doors. Yeah?” he said again.

“How do we know which line to get on?” Sonny asked.

There was a National Park Service patch sewn to the ranger’s shirt over his left pectoral. A little brass National Park Service shield was pinned over the pectoral on the right. Below the shield was a narrow brass rectangle with the ranger’s name stamped onto it: ALVIN RHODES.

“Where do you want to go?” he asked.

“Well, until we know which line goes where ,” Sonny said, “how can we...?”

“The line on the left is for people who don’t know where they’re going,” the ranger snapped, and then began chanting again, “Admission is to the right or left, depending where you want to go. No admission through the...”

As it turned out, the line on the left wasn’t for people who didn’t know where they were going, but was instead for people who wanted to climb the stairs going up to the crown. A girl tending the rope at the head of the line told Sonny they were looking at a twenty-two-story climb...

“That’s three hundred and fifty-four steps,” she said.

... and maybe a wait of two to three hours. If they wanted her advice, they’d get on the other line and take the elevator up to the pedestal.

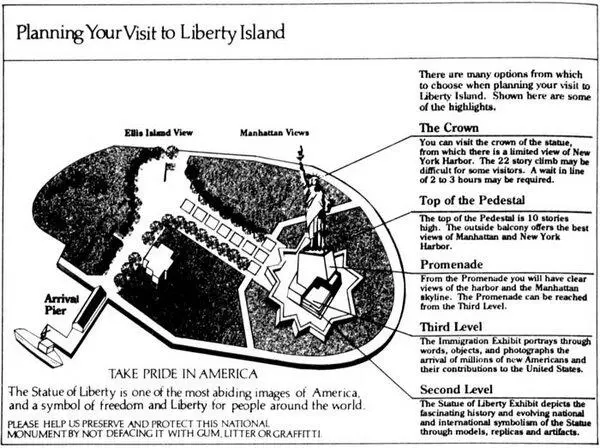

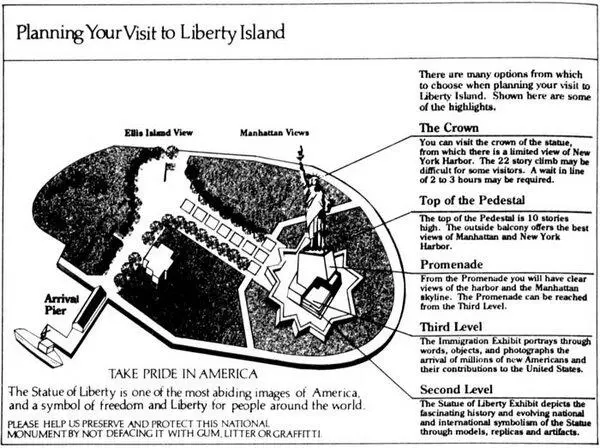

“Get a good view of the harbor all around that way, save yourself a lot of sweat and strain. Here’s a plan, shows you where the pedestal is,” she said, and handed him a printed drawing of the “Planning Your Visit” sign he’d photographed on the mainland:

“What do you think?” he asked Elita.

“Sounds good to me,” she said.

“I’ll let you through,” the girl said. “Just cross over to the other line.”

“Thank you,” Sonny said.

He was thinking he would remember Alvin Rhodes. He was thinking, I hope you’re here on the Fourth, Alvin .

They were in the open space where Liberty’s original torch was now displayed, a large rectangle surrounded by an upper level, which he guessed was the Second Level indicated on the Planning Your Visit sketch. As they walked toward the people waiting on line for the elevator, Sonny looked up and saw signs indicating there were restrooms upstairs. He spotted a staircase, took Elita’s elbow, said, “There are restrooms up there,” and led her toward the steps. She wondered if he had read her mind.

The men’s room was on one side of the open rectangle, the ladies’ room on the other. Again, their agendas were different. Elita simply had to pee. Sonny was looking for a likely lay-in spot, should the plan call for one. An open wooden door led into an angled alcove that shielded the men’s room from the corridor outside. He ran his palm over the door, seemingly studying the paint job, while actually checking out the lock. A man passing by looked at him curiously, and Sonny said, as if commenting admiringly, “They painted it to look like bronze,” which in fact they had. The man nodded in vague agreement and hurried into one of the stalls. The lock on the door was a spring latch, fitted with a keyway on the outside. A wooden wedge held the door open. Sonny glanced behind the door and saw a push bar on the inside. Mickey Mouse time.

There was another door in the little alcove, painted grey and right-angled to the entrance door. Someone had left it either accidentally or deliberately ajar, open perhaps some eight to ten inches. As Sonny passed it, he glanced into the darkened room beyond and saw a pail with a mop in it. The room was a utility closet. The outside of the door was fitted with a circular keyway. He walked past at once, hurrying through into the main section of the restroom. There were the requisite number of urinals, stalls and sinks. You could lay in overnight in a stall, but if a cleaning man came in to mop up—

The man who’d agreed with him about the imitation bronze door was coming out of the closest stall. He washed his hands at one of the sinks, glanced sourly at the blowers attached to the wall, dried his hands on his handkerchief instead, and left the room. Sonny took a position at the end of the row of urinals. A man at the other end was taking forever to pee. Sonny waited for him to finish, waited for him to leave the room — without washing his hands — and then zipped up his fly. He went to the sinks, quickly washed his hands, dried them inadequately on one of the wall blowers, and moved immediately to the grey utility closet door. He yanked the door all the way open, checked its inside surface in an instant. A thumb latch. Nothing else. No knob on the door, no push bar. Just the latch, designed to spring the lock in case someone accidentally trapped himself inside. He feigned elaborate surprise at having entered a closet. But there was no one in sight as he backed out into the alcove again; his little act hadn’t been necessary at all.

Читать дальше