“I tried to call Mother,” he said, “but...”

“Mother is dead.”

A silence on the line.

Sonny waited.

“Where are you now?” she asked.

“The Hilton. Room 2312.”

“When are you available?”

“I’m available now.”

“Can you come here?”

“Where are you?”

She gave him an address on the upper east side.

“Give me half an hour,” he said.

“I’ll be expecting you,” she said.

He waited.

There was a silence on the line. She was waiting for his prompt.

“And will you be there?” he asked, supplying it.

He would not go to meet her unless she responded correctly.

“You can be sure,” she said.

He had never seen the woman he’d known on the telephone as Priscilla Jennings. His control. Mother. The woman who, he’d been told, would one day awaken him from sleep. The woman who had, in fact, awakened him last Saturday morning.

Now he wondered what she’d looked like.

His new control — if such she turned out to be — was a woman in her mid-fifties, he supposed. Dark brown eyes, a vaguely Mediterranean look about her except for the reddish-blond hair, clipped close to her skull like a medieval archer’s helmet. She was wearing a grey cotton cardigan buttoned up the front over ample breasts. Her dark skirt was festooned with cat hairs. There were cats everywhere Sonny looked. At least ten or twelve cats in the apartment, one of them sleeping on the windowsill, another perched on the upright piano, yet more flopped on cushions or silently stalking the small apartment. Everywhere, there was the faint aroma of cat piss. Mrs. Fleischer poured tea. Sonny listened to the sounds of summer filtering up from the street and through the open window where the cat snoozed. He was thinking that never in a million years would anyone guess this woman was one of them.

“So,” she said. “When did you arrive?”

“This afternoon,” he said.

Not a trace of accent in her speech. She could have been Greek or Turkish, even Israeli, but nothing in her speech revealed a country of origin. Her hand pouring the tea was steady.

“Where’s Priscilla Jennings?” he asked.

“Pardon?” she said, and raised her eyebrows. Faint polite inquisitive look on her face.

“Priscilla,” he said. “Jennings.”

“I don’t believe I know her,” Mrs. Fleischer said. “Milk? Lemon?”

“Lemon, please.”

She caught a wedge of lemon between the jaws of a small pair of silver tongs. She dropped it on his saucer. She passed the saucer to him. He was wondering why she was now denying the existence of his previous control. She had acknowledged her name on the phone — but no, she may only have been confirming the s-c sequence. It was quite possible she knew nothing at all about her. Yet she had informed him that Mother was dead. What...?

“Did you get a chance to sleep on the train?” she asked.

“Yes,” he said, and thought suddenly of Elita. And just as quickly put her out of his mind.

“Are you well rested then?” Mrs. Fleischer asked.

“Completely.”

“Completely awake?” she asked.

“I’m an early riser,” he said.

Their eyes met.

She smiled.

“I have your instructions,” she said.

Voice low and steady.

He had been waiting for these instructions from the time he was eighteen. He had come to America eleven years ago, trained and prepared, and had been anticipating these instructions ever since. He leaned forward now.

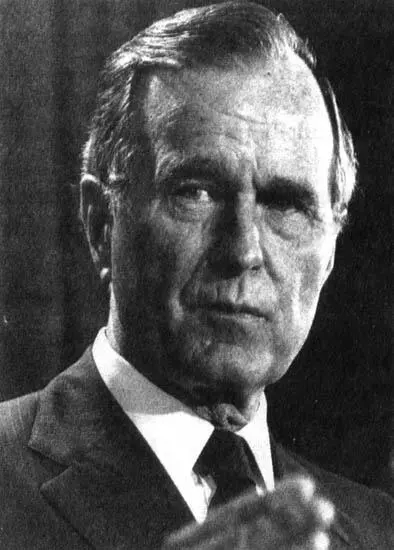

She opened her handbag. She removed from it a glossy black-and-white photograph, some three inches wide by four inches long. Handing it to him, she said, “She’ll be here for the Canada Day celebration on the first of July. Security will be tight, access difficult.”

He looked at the photograph.

And felt mild disappointment.

Had they awakened him for this? Merely this?

“The celebration will take place at the Plaza Hotel on Fifth Avenue and Central Park South, are you familiar with it?”

“Yes,” he said.

“The Prime Minister of Canada will be there, of course, as well as the President of Mexico. But Mrs. Thatcher is only your secondary target. Your primary target...”

“Yes, who will that be?”

“... may or may not be present at the dinner that night, we haven’t been able to ascertain that as yet. In any event, you must not do anything to jeopardize your main objective. There’s a possibility you can kill two birds with one stone, so to speak...”

A faint smile.

“... but only if your primary target...”

“Who?” he asked.

“... is present at the dinner and ball. Otherwise, you’ll have to wait till the Fourth of July,” she said, and grimaced. “Their big holiday, Inde pen dence Day. There’ll be a ceremony at the Statue of Liberty which he is scheduled to...” She hesitated, studied his face. “They told me you were familiar with New York.”

“I am.”

“You seemed puzzled when I mentioned the Statue of...”

“No, I was only wondering who .”

“I want to make certain, first, that you understand you can’t be diverted from...”

“Yes, I do understand.”

“The whore is relatively minor.”

“Yes.”

“If you can accomplish both objectives, all to the good. But you mustn’t sacrifice purpose to expediency. Forget her if you must...” A nod toward the photograph in his hand. “But get him .”

“Yes, who?” he asked again.

She handed him another small photograph.

“Him,” she said.

Sonny looked at the picture.

And then, truly puzzled now, he looked up at Mrs. Fleischer.

“The whore because...”

“Yes, I realize, but...”

“... without her, the bombing would have been impossible.”

“Yes, but...”

“He has not forgotten,” she said. Hatred burning in her eyes now.

“ None of us has forgotten.” The hatred leaping into his own eyes, enflaming them. “But...”

“Nor has God forgotten. Or forgiven.”

“Allah be praised,” Sonny said.

“Praise God, for there is no God but He.”

There was a silence. They sat staring at each other, memories flaring. One of the cats mewed softly. The silence lengthened. At last, Sonny asked, “But why have we chosen...?”

“This will make it clear to you,” she said, and handed him an envelope. “The letter will explain. When you’ve read it...”

He was already reaching into the envelope.

“Not now,” she said. “There’s a telephone number in the envelope. Call it after you’ve read the letter. Ask for Arthur Scopes. You are not to contact me again. I have never entered your life, I no longer exist. Do you understand?”

“I understand,” he said.

“May God go with you,” she said, and snapped her handbag shut.

The click sounded utterly final.

Carolyn Fremont was in the midst of packing for the move to Westhampton Beach, carrying clothing from her bedroom dresser to the open suitcase on her bed. Elita was slumped listlessly in an armchair near the window in her mother’s bedroom, early morning sunlight streaming through the partially cracked blinds, touching her blond hair with fire. Carolyn knew the signs well; Elita was in love again. Or, worse, Elita was in love again and had once again been abandoned.

Читать дальше