Of course it hadn’t.

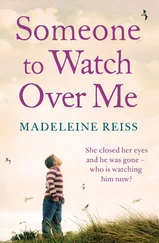

There was no way they could possibly know that the Ruth Innes who had married Alec Morrison fourteen years ago had died in a house fire in Melrose, along with her mother, stepfather and two brothers, when she was six years old. Not unless they’d taken the details off her birth certificate and used them to trawl through the death records.

And they obviously hadn’t done so, or this wouldn’t be happening. The home visit was just the final step in the process; the rubber-stamping of the approval of Alec and Ruth Morrison as potential adopters.

She looked down the little single-track road. After the night’s high winds, the tarmac was carpeted with a fresh fall of coppery beech leaves – all colours of copper, from newly polished to dull and tarnished. The huge old beech trees along one side of the road arched their pale, thick branches up and up against the bright china blue of the sky, and on the other side a stubbly field rose from the hedge up the slope to the plantation. There was no sound, except for a bird somewhere in the wood, chattering a complaint.

It was beautiful.

It was going to be fine.

Deirdre Jack could have no concerns about Ruth or she’d already have voiced them. Her main worry was probably the carbon footprint she was leaving in coming all the way out here from Glasgow – although Alec would say she probably felt carbon footprints didn’t apply to people with socially responsible jobs. Maybe she was enjoying the drive. Singing along to Emmylou Harris or Nanci Griffith. Looking forward to spending a pleasant morning in pleasant company.

Deirdre was coming not to interrogate them again but to check out their home, the environment in which they were proposing to bring up a child.

Which was beautiful.

Which was perfect.

Wasn’t it?

It was going to be fine?

She looked up at the sky, an unbroken blue apart from one high wispy little cloud.

Did all this baseless worrying have at its root her desperation to adopt a child, her fear that she was going to be knocked back at the final hurdle, or was it her brain’s way of telling her that this wasn’t right? That this wasn’t what she wanted at all?

She walked a little way along the road. Amongst the beech leaves were scatterings of crushed beech nuts where tyres had run over them. All the trees that would never be. She stooped to pick up an intact nut and close her hand on it, its spikes prickling her palm.

And now she was there at her side.

Ruth had known she would come, her face turned up to her with a smile – rosy cheeks, a woolly red hat, blue and green stripy-gloved hands full of the brightest leaves for the collage they’d make later at the kitchen table.

‘Darling,’ she whispered, like a madwoman. ‘No. No more.’

She had only ever confided in one person about her daydreams of this unborn, unnamed child – and that one person had been Sara, the woman she’d been paired with by the agency, who had adopted three children through them. She’d been so lovely, Sara, a woman made to be a mother if anyone was, and Ruth had found herself confessing that she fantasised, regularly, about an unconceived, unborn, never-to-be child.

Sara had smiled, and nodded, and told her she used to do the same.

‘I’m so scared,’ Ruth had gulped. ‘I’m so scared I won’t love the little girl we adopt as I would have loved my own.’ Scared about other things too, of course, but those fears she would never, ever blurt out to anyone, let alone a virtual stranger.

Sara had grabbed Ruth’s hand. ‘Oh no no no , you mustn’t worry about that! She will be your own , and you’ll love her so much . You’ll love her as you’ve never loved anyone in your life . You’ll love her just as much, maybe even more than if she’d been biologically yours.’

But those were just words, a politically correct recitation of what you were meant to feel.

Maybe it was fifteen years of living with Alec, or maybe it was the pragmatism that nurses seemed to have inbuilt or to develop, but she had a horrible suspicion that blood ties mattered. They were the basis of life, after all, of evolution, of animal behaviour. Human behaviour. Her own experience of the neonatal unit had shown her just how strong, how primeval, was the bond between a mother and her child. Her own child. Her own flesh and blood child.

The little stranger who was out in the world somewhere waiting for Ruth, waiting to be loved as every child deserved to be loved, was counting on her to love her like a flesh and blood mother would.

‘Go,’ she said. ‘Go.’

She threw the beech nut to the verge. And her never-to-be little girl flung out her arms and ran, full tilt, red wellies kicking through the leaves, running away from her down the road without a backward glance.

‘Go.’

Stupid stupid stupid , to be crying. To be thinking that if there was a heaven, if by some remote chance it existed, surely there must be a place in it for her own child, a place where all the never-to-be children waited for their mothers.

So stupid .

But as the little figure blurred and faded, as she found a tissue in her pocket and blew her nose and laughed at herself, as she looked back at the road, at nothing, she let her never-to-be mother’s love fill her heart and spill over and speak itself aloud, just once, to the empty air:

‘I would have loved you… I would have loved you mo–’

But before the last word had quite left her lips, she had put a hand to her mouth to stop it. The woman Deirdre was about to meet would never think that. Ruth Morrison would be horrified at the very thought that an adopted child could be any less loved than a biological one. Less wanted. Less valued. Less worthy.

Such a possibility would never even cross Ruth Morrison’s mind.

‘Right, let’s make a start, then,’ goes the sheriff woman. ‘Ladies and gentlemen. This Court of Session is sitting to determine an application for a permanence order, with authority to adopt, by Glasgow City Council in respect of the child Bekki Johnson. The application is opposed by the child’s grandparents, Jed and Lorraine Johnson.’ She takes off her glasses, looks right at me and starts on about what a permanence order is, like I’m a daftie, like I dinnae even know what it is I’m fucking fighting.

I know what a permanence order is. It’s the fucking system saying Bekki’s gonnae be adopted by fucking randoms and there’s nothing we can do about it.

Our fucking Bekki .

The sheriff bumps her gums, blah fucking blah, and then Mair gets up, in her white silk shirt and wee black skirt and I’m-so-down-with-the-kids nose stud. If it wasnae for Bekki, I’d swing for her so I would.

She goes to the box thingmie like a sheep pen in front of the sheriff’s bench. She sits on the chair inside it and puts her papers down in front of her, like she’s so fucking professional.

‘Ms Mair.’ The lawyer who’s for the Council gets up. The lawyers have this big table in the middle of the courtroom court room with computers and that. ‘Could you describe for the sheriff what your role has been in this case?’ Bastard’s English. Fwah fwah fwah .

‘I’m the social worker assigned to Bekki Johnson’s case. I’m the author of the permanence order report, Lady Semple, which I think you have there…’ The smug face on her, like Bekki’s an exam question she’s aced.

Sheriff goes, ‘Yes, thank you, Ms Mair. A very clear, comprehensive report it is too.’

Aye, a very clear, comprehensive load of shite.

Fwah : ‘Perhaps you could give us some brief background on Bekki and her family situation, Ms Mair?’

Читать дальше