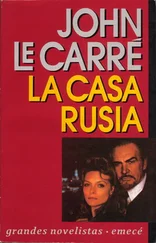

Write his words.

This is Daniil. Is that Mariya speaking? My lecture was the greatest success of my career. That was a lie.

Why?

He says always, in Russia the only success is not to win. It is a joke we have. He spoke deliberately against our joke. He was telling me we are dead.

Barley went to the window and looked steeply down at the concourse and the street. The whole dark world inside him had fallen into silence. Nothing moved, nothing breathed. But he was prepared. He had been prepared all his life, and never known it. She is Goethe's woman, therefore she is as dead as he is. Not yet, because this far Goethe has protected her with the last bit of courage left in him. But dead as dead can be, any time they care to reach out their long arm and pick her off the tree.

For perhaps an hour he remained there at the window before returning to the bed. She was lying on her side with her eyes open and her knees drawn up. He put his arm round her and drew her into him and he felt her cold body break inside his grasp as she began sobbing with convulsive, soundless heaves, as if she was afraid even to weep within the hearing of the microphones.

He began writing to her again, in bold clear capitals: PAY ATTENTION TO ME.

The screens were rolling every few minutes. Barley has left the Mezh. More. They have arrived at the metro station. More. Have exited ( sic ) the hospital, Katya on Barley's arm. More. Men lie but the computer is infallible. More.

'Why on earth's he driving?' Ned asked sharply as he read this.

Sheriton was too absorbed to reply but Bob-was standing behind him and Bob picked up the question.

'Men like to drive women, Ned. The chauvinist age is still upon us.'

'Thank you,' said Ned politely.

Clive was smiling in approval.

Intermission. The screens slip out of sequence as Anastasia takes back the story. Anastasia is an angry old Latvian of sixty who has been on the Russia House books for twenty years. Anastasia alone has been allowed to cover the vestibule.

The legend speaks:

She made two passes, first to the lavatory, then back to the waiting room.

On her first pass, Barley and Katya were sitting on a bench waiting.

On her second, Barley and Katya were standing beside the telephone and appeared to be embracing. Barley had a hand to her face, Katya also had a hand up, the other hung at her side.

Had Bluebird's call come through by then?

Anastasia didn't know. Though she had stood in her lavatory cubicle listening as hard as she could, she hadn't heard the phone ring. So either the call had failed to come through or it was over by the time she made her second pass.

'Why on earth should he be embracing her?' said Ned.

'Maybe she had a fly in her eye,' Shcriton said sourly, still watching the screen.

'He drove,' Ned insisted. 'He's not allowed to drive over there, but he drove. He let her drive all the way out to the country and back. She drove him to the hospital. Then all of a sudden he takes over the wheel. Why?'

Sheriton put down his pencil and ran his forefinger round the inside of his collar. 'So what's the betting, Ned? Did Bluebird make his call or didn't he? Come on.'

Ned still had the decency to give the question honest thought. 'Presumably he made it. Otherwise they would have gone on waiting.'

'Maybe she heard something she didn't like. Some bad news or something,' Sheriton suggested.

The screens had gone out, leaving the room sallow.

Shcriton had a separate office done in rosewood and instant art. We decamped to it, poured ourselves coffee, stood about.

'Hell's he doing in her flat for so long?' Ned asked me aside. 'All he has to do is get the time and place of the meeting out of her. He could have done that two hours ago.'

'Maybe they're having a tender moment,' I said.

'I'd feel better if I thought they were.'

'Maybe he's buying another hat,' said Johnny unpleasantly, overhearing us.

'Geronimo,' said Shcriton as the bell rang, and we trooped back to the situation room.

An illuminated street map of the city showed us Katya's apartment marked by a red pinlight. The pick-up point lay three hundred mctres cast of it, at the south-east corner of two main streets marked green. Barley must now be heading along the south pavement, keeping close to the curb. As he reached the pick-up point, he should affect to slow down as if hunting for a car. The safe car would pull alongside him. Barley had been instructed to give the driver the name of his hotel in a loud voice and negotiate a price with his hands.

At the second roundabout the car would take a side turning and enter a building site where the safe truck was parked without lights, its driver appearing to doze in his cab. If the truck's wing aerial was extended, the car would make a right-hand circle and return to the truck.

If not, abort.

Paddy's report hit the screens at one a.m. London -time. The tapes were available for us less than an hour later, blasted from the roof of the US Embassy. The report has since been torn to pieces in every conceivable way. For me it remains a model of factual field reporting.

Naturally the writer needs to be known, for every writer under the sun has limitations. Paddy was not a mindreader but he was a lot of other things, a former Gurkha turned special forces man turned intelligence officer, a linguist, a planner and improviser in Ned's favourite mould.

For his Moscow persona, he had put on such a skin of English* silliness that the uninitiated made a joke of him when they described him to each other: his long shorts in the summer when he took himself on treks through the Moscow woods; his langlaufing in the winter, when he loaded up his Volvo with ancient skis and bamboo polcs and iron rations and finally his own egregious self, clad in a fur cap that looked as though it had been kept over from the Arctic convoys. But it takes a clever man to act the fool and get away with it for long, and Paddy was a clever man, however convenient it later became to take his eccentricities at face value.

Also in controlling his motley of pscudo language students, travel clerks, little traders and third-flag nationals, Paddy was first rate. Ned himself could not have bettered him. He tended them like a canny parish priest, and every one of them in his lonely way rose to him. It was not his fault if the qualities that made men come to him also made him vulnerable to deception.

So to Paddy's report. He was struck first by the precision with which Barley gave his account, and the tape bears him out. Barley's voice is more self-assured than in any previous recording.

Paddy was impressed by Barley's resolve and by his devotion to his mission. He compared the Barley he saw before him in the truck with the Barley he had briefed tor his Leningrad run and warmed to the improvement. He was right. Barley was an enlarged and altered man.

Barley's account to Paddy tallied also with every check able fact at Paddy's disposal, from the pick-up at the metro and the drive to the hospital, to the wait on the bench and the stifled bell. Katya had been s ' tanding over the phone when it rang, Barley said. Barley himself had scarcely heard it. Then no wonder Anastasia hadn't heard it either, Paddy reasoned. Katya must have been quick as light to grab that receiver.

The conversation between Katya and the Bluebird had been short, two minutes at most, said Barler. Another neat fit. Goethe was known to be scared of long telephone conversations.

With so much collateral available to him therefore, and with Barley navigating his way through it, how on earth can anybody afterwards maintain that Paddy should have driven Barley straight to the Embassy and shipped him back to London bound and gagged? But of course Clive maintained just that, and he was not the only one.

Читать дальше