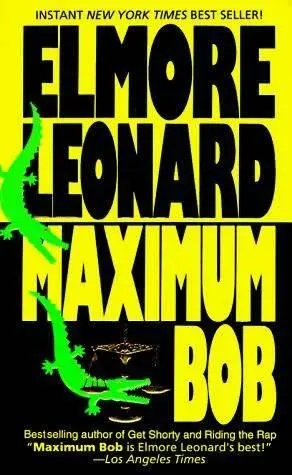

Elmore Leonard

Maximum Bob

Dale Crowe Junior told Kathy Baker, his probation officer, he didn’t see where he had done anything wrong. He had gone to the go-go bar to meet a buddy of his, had one beer, that’s all, while he was waiting, minding his own business and this go-go whore came up to his table and started giving him a private dance he never asked for.

“They move your knees apart to get in close,” Dale Crowe said, “so they can put it right in your face. This one’s name was Earlene. I told her I wasn’t interested, she kept right on doing it, so I got up and left. The go-go whore starts yelling I owe her five bucks and this bouncer come running over. I give him a shove was all, go outside and there’s a green-and-white parked by the front door waiting. The bouncer, he tries to get tough then, showing off, so I give him one, popped him good thinking the deputies would see he’s the one started it. Shit, they cuff me, throw me in the squad car, won’t even hear my side of it. Next thing, they punch me up on this little computer they have? The one deputy goes, ‘Oh, well look it here. He’s on probation. Hit a police officer.’ Well, then they’re just waiting for me to give ‘em a hard time. And you don’t think I wasn’t set up?”

This morning Dale Crowe Junior was back in the Criminal Division of Palm Beach County Circuit Court. In a holding cell crowded with offenders wearing state-blue uniforms that were like hospital scrubs. Blue shapes standing around in the semi-dark. Kathy Baker recognized some of them. They’d step into the light to say hi through the wall of bars. Mostly black guys in there, they’d ask how she was doing. Kathy would shrug. Same old business, hanging out in bad company. She told Dale Crowe, holding open his case file, he must be in a hurry to do time. Two days out of jail he was back in.

“I haven’t even had a chance to fill out your post-sentence sheet, you’re in violation.”

“‘Cause I went to a go-go joint? Nobody said I couldn’t.”

“When were you around to tell you anything? You were suppose to report to the Probation Office, Omar Road.”

“They said I had seventy-two hours. I been going out to the sugar house, seeing how to get my job back.” Dale turned his head to one side in the noise of voices and said, “Hey, we’re trying to talk here.”

The blue shapes in the dark paid no attention to him. Kathy moved closer to the bars. She could smell Dale now.

“The police report says you were drinking.”

“One beer, that’s all. I urine-tested clean.”

“But you’re underage. You broke the law and that violates your probation.”

Dale Crowe Junior was twenty, a tall, bony-looking kid in his dark-blue scrubs. Dark hair uncombed, dumb eyes wandering, worried, but trying to look bored. Dale was from a family of offenders in and out of the system. His uncle, Elvin Crowe, had this week completed his prison time on a split sentence and was beginning his probation.

Kathy Diaz Baker was twenty-seven, a slim five-five in her off-white cotton shirtdress cinched with a belt. No makeup this morning, her dark hair permed and cut short in back, easy to manage. She spoke with a slight Hispanic accent, the Diaz part of her, that was comfortable, natural, though she could speak without a trace of it if she wanted. The Baker part of her was from a marriage that lasted fourteen months. She had met all kinds of Dale Crowes in her two years with the Florida Department of Corrections and knew what they could become. His uncle, Elvin Crowe, had recently been added to her caseload.

“I can go to jail but I can’t have a beer?”

“Listen, I spoke to your lawyer-”

“You don’t think I stop and have a few after work, driving a cane truck all day? I never get carded either, have to show any proof.”

“You through?” Kathy watched him take the bars in his hands and try to shake them. “I had a talk with your lawyer.”

“Little squirt, right? He’s a public defender.”

“Listen to me. He’s going to plead you straight up, but try to make it sound like a minor violation. It’s okay with the state attorney. She’ll leave it up to the judge, as long as you plead guilty.”

“Hey, shit, I didn’t do nothing.”

“Just listen for a minute, okay? You plead not-guilty and ask for a trial, the judge won’t like it. They’ll find you guilty anyway and then he’ll let you have it for wasting the court’s time. You understand? You plead guilty and act like you’re sorry, be polite. The judge might give you a break.”

“Let me off?”

“He’ll ask for recommendations. The state attorney will probably want you to do a little time.”

“‘Cause I had a beer ?”

“Maybe ask you to do some work release, out of the Stockade. Try to be cool, okay? Let me finish. Your lawyer will recommend reinstating your probation, say what a hardworking guy you are. He won’t mention you got fired unless it comes up, but don’t lie, okay? This judge,” Kathy said, “I might as well tell you, is very weird. You never know for sure what he’s going to do. Except if you act smart and he doesn’t think you’re sorry, kiss your mom and dad good-bye, you’re gone.”

“What one have I got?”

“Judge Gibbs.”

It seemed to please him. “Bob Isom Gibbs, I know him, the one they call ‘Big.’ Election time you see his name on signs, ‘ Think Big .’ He’s famous, isn’t he?”

“He makes himself known.”

“He’s the one sent my uncle Elvin away.”

“Dale, he’s put more offenders on death row than any judge in the state.” That shut him up. “What I’m trying to tell you is be polite. Okay? With this judge you don’t want to piss him off.”

Dale was shaking his head, innocent. He said, “Man, I don’t know,” in a sigh, blowing out his breath, and Kathy turned her face away. “You gonna tell him how you see this?”

“When the judge asks for recommendations, yeah, I’ll have to say something…”

“Well, that’s good. Tell him I’ve been drinking since I was fourteen years old and I know how, no problem. Listen, and tell him I’m still working out the sugar house. Have a good job and don’t want to lose it.”

“Anything else?”

“That’s all I can think of.”

“Just lie for you?”

“It wouldn’t hurt you none, would it? Say I’m working? Jesus.”

“You think I’m on your side?”

“Well, aren’t you?”

“Dale, I’m not your friend. I’m your probation officer.”

***

She left the holding cell, the dark shapes, the noise, passed through locked doors to a well-lighted hallway and was back in the world among sport shirts and flowered dresses, people waiting for court sessions.

“What’s the matter?”

Kathy looked up. It was Marialena Reyes with her fat briefcase, the assistant state attorney who would be prosecuting Dale Crowe in about ten minutes. She was a friend of Kathy’s, a woman in her forties, unmarried, dedicated to her work, this morning in a brown linen suit that needed to be pressed.

“I just talked to him,” Kathy said, and shook her head.

“What else is new?”

“Nothing changes. They look at me, I’m this girl who comes around with a clipboard checking up. Like a social worker.”

“It’s up to you. I’ve quit saying go back to school, get a law degree.”

“I’m in court enough as it is. What will Dale get?”

Читать дальше