A Chevy Tahoe cruised along the parking lane, but Ryan didn’t hail the driver. He wanted only to get out of there and home.

He heard her voice in memory: I can kill you any time I want.

Having been excited by the drawing of his blood, maybe she would decide she needed to come back and kill him now.

The Ford single overhead cam 427, built solely for racing, had enough torque to rock the car as it idled. Behind the engine was a Ford C-6 transmission with 2,500-rpm stall converter.

Leaving the parking lot, Ryan was tempted to take the streets as if they were the race lanes of a Grand Prix, but he stayed at the posted speed limits, loath to be pulled over by the police.

The car was not a classic but a hot rod, totally customized, and Ryan had hands-free phone technology aboard. His cell rang, and even in his current state of mind, he automatically accepted the call. “Hello.”

The woman who had slashed him said, “How is the pain?”

“What do you want?”

“Do you never listen?”

“What do you want?”

“How could I make it any clearer?”

“Who are you?”

“I am the voice of the lilies.”

Angrily, he said, “Make sense.”

“They toil not, neither do they spin.”

“I said sense, not nonsense. Is Lee there? Is Kay?”

“The Tings?” She laughed softly. “Do you think this is about them?”

“You know them, huh? Yeah, you know them.”

“I know everything about you, who you fire and who you use.”

“I gave them two years’ severance. I treated them well.”

“You think this has to do with the Tings because my eyes are slanted like theirs? It has nothing to do with them.”

“Then tell me what this is about.”

“You know what it’s about. You know.”

“If I knew, you wouldn’t have gotten close enough to cut me.”

A red traffic light forced him to stop. The car rocked, and under the blood-soaked chamois, the stinging incision pulsed in time with the idling engine.

“Are you really so stupid?” she asked.

“I have a right to know.”

“You have a right to die,” she said.

He thought at once of Spencer Barghest in Las Vegas and the collection of preserved cadavers. But he had never found a connection between Dr. Death and anything that happened sixteen months previous.

“I’m not stupid,” he said. “I know you want something. Everyone wants something. I have money, a lot of it. I can give you anything you want.”

“If not stupid,” she said, “then grotesquely ignorant. At best, grotesquely ignorant.”

“Tell me what you want,” he insisted.

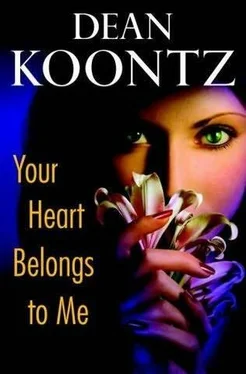

“Your heart belongs to me. I want it back.”

The irrationality of her demand left Ryan unable to respond.

“Your heart. Your heart belongs to me,” the woman repeated, and she began to cry.

As he listened to her weeping, Ryan suspected that reason would not save him from her, that she was insane and driven by an obsession that he could never understand.

“Your heart belongs to me.”

“All right,” he replied softly, wanting to calm her.

“To me, to me. It is my heart, my precious heart, and I want it back.”

She hung up.

A horn sounded behind him. The traffic light had changed from red to green.

Instead of pressing on, Ryan pulled to the side of the road and put the car in park.

Using the *69 function, he tried to ring back the weeping woman. Eventually the attempted call brought only a recorded phone-company message requesting that he either hang up or key in a number.

When he had a break in traffic, Ryan drove back into the street.

The sky was high and clear, an inverted empty bowl, but the forecast called for rain late Sunday morning, continuing until at least Monday afternoon. When the bowl was full and spilling, she would come. In the dark and rain, hooded, she would come, and like a ghost, she would not be kept out by locks.

Ryan parked the deuce coupe and got out, relieved to find the garage deserted. Standing at the open car door, he withdrew the blood-soaked chamois from inside his shirt, dropped it on the quilted blanket that protected the driver’s seat, and pressed a clean cloth over the wound.

Quickly, he folded the bloody chamois into the blanket, held the blanket under his left arm, against his side, and went into the house. He rode the elevator to the top floor and reached the refuge of the master suite without encountering anyone.

He put the blanket aside, intending to bag it later and throw it in the trash.

In the bathroom, he washed the wound with alcohol. Subsequently he applied iodine.

He almost relished the stinging. The pain cleared his head.

Because the cut was shallow, a thick styptic cream stopped the bleeding. After a while, he gently wiped the excess cream away and spread on Neosporin.

The rote task of dressing the wound both focused him on his peril and freed his mind to think through what must happen next.

To the Neosporin, he stuck thin gauze pads. Once he had applied adhesive tape at right angles to the incision, to help keep the lips of it together, he ran longer strips parallel to the wound, to secure the shorter lengths of tape.

The pain had diminished to a faint throbbing.

He changed into soft black jeans and a black sweater-shirt with a spread collar.

The master-retreat bar included a little wine storage. He opened a ten-year-old bottle of Opus One and filled a Riedel glass almost to the brim.

Employing the intercom, he informed Mrs. Amory that he would turn down the bed himself this evening and that he would take dinner in the master suite. He wanted steak, and he asked that the food-service cart be left on the penthouse landing at seven o’clock.

At a quarter till five, he called his best number for Dr. Dougal Hobb in Beverly Hills. On a weekend, he expected to get a physicians’ service, which he did. He left his name and number and stressed that he was a transplant patient with an emergency situation.

Sitting at the amboina-wood desk, he switched on the plasma TV in the entertainment center and muted the sound, staring at 1930s gangsters firing noiseless machine guns from silent black cars that glided around sharp corners without the bark of brakes or rubber.

Having drunk a third of the wine in the glass, he held his right hand in front of his face. It hardly trembled anymore.

He changed channels and watched an uncharacteristically taci-turn Russell Crowe captain a soundless sailing ship through a furious but silent storm.

Eleven minutes after Ryan had spoken to the physicians’ service, Dr. Hobb returned his call.

“I’m sorry if I alarmed you, Doctor. There’s no physical crisis. But it’s no less important that you help me with something.”

As concerned as ever, with no indication of ill temper, Hobb said, “I’m always on call, Ryan. Never hesitate if you need me. As I warned you, no matter how well the recovery goes, emotional problems can develop suddenly.”

“I wish it were that simple.”

“The phone numbers of the therapists I gave you a year ago are still current, but if you’ve misplaced them-”

“This isn’t an emotional problem, Doctor. This is…I don’t know what to call it.”

“Then explain it to me.”

“I’d rather not right now. But here’s the thing-I’ve got to know who was the donor of my heart.”

“But you do know, Ryan. A schoolteacher who suffered massive head trauma in an accident.”

“Yeah, I know that much. She was twenty-six, would be twenty-seven now, going on twenty-eight. But I need a good photograph of her.”

For a beat, Hobb was as silent as Russell Crowe’s ship when it plowed through hushed seas so terrible that sailors were lashed to their duty stations to avoid being washed overboard.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу